Early in the 1985 documentary Tokyo Melody, Ryuichi Sakamoto comments on creating art chronologically…or rather, not. “Time is no longer linear. Time does not develop in one way. We can compose music and put it in any order we like.”

This position becomes the film’s own approach to capturing the Japanese artist, eschewing straight-ahead narrative in favor of a collage-like view of Sakamoto. In just over an hour viewers see Sakamoto as musician, actor, tinkerer, husband, French-speaker, pitchman and more. It’s a fragmented portrait of the prolific musician, and one of the best.

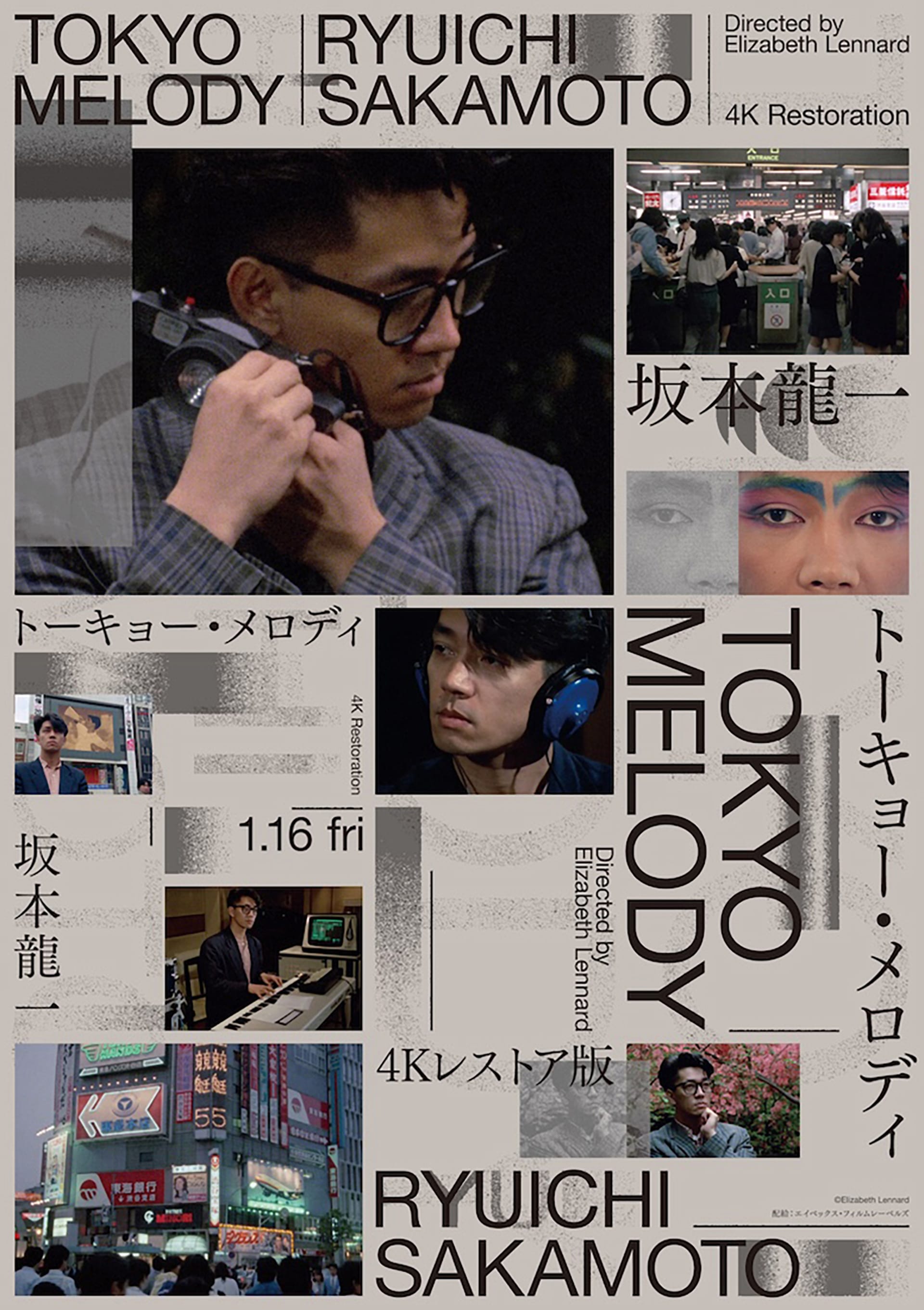

Directed by Elizabeth Lennard over a single frantic-sounding week in 1984, Tokyo Melody has long been a rare cinema presence, popping up at festivals and special screenings around the world in the decades since (and, of course, clips finding a home on YouTube). This month a new 4K restoration of the documentary premiered in Tokyo, and is in select theaters across the country. It looks great (and, if you are willing to splurge a bit, can be experienced at Shinjuku’s 109 Cinemas Premium, featuring a soundsystem overseen by Sakamoto) but more importantly it being back in the world allows people to experience one of the best peaks into the creator’s mind ever captured.

Since his death in 2023, no shortage of tributes and looks into Sakamoto’s life have appeared, to the point a different one was on the schedule at 109 Cinemas Premium the day I went with a trailer promising another in the months ahead. Tokyo Melody stands out by unfolding in a non-linear style shaped by his own ethos. Ostensibly though, this is a documentary capturing Sakamoto creating his album Ongaku Zukan (Illustrated Musical Encyclopedia). There’s footage of him in the studio playing the piano, eating dinner while engineers tinker away at his sketches and, in the most fascinating moment in terms of creation, showcasing how a bulky Fairlight CMI synthesizer (watching him hold up biggie-sized floppy disks and then operate this thing is magical).

Despite these glimpses into his workspace, Tokyo Melody is much more than a making-the-album affair. We get interviews with Sakamoto digging into his approach, his opinion on the society of the 1980s (“Japan has become the leading capitalist country”) and even his take on DJ scratching. That’s mixed in with concert footage of Yellow Magic Orchestra, scenes from Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence, artier shots of Sakamoto standing in front of ads featuring Sakamoto, and at its most intimate a piano duet between him and then-wife Akiko Yano.

An accidental strength of Tokyo Melody is as a document of Japan’s Bubble era, a period now romanticized by people both domestically and abroad but rarely captured as something other than middle-class fantasy. Lennard spends almost as much of the film’s length capturing the feel of Tokyo in the mid 1980s as she does Sakamoto, using it as artistic metaphor but also offering striking documentation. She captures the capital from all angles, from the hustle of electronic stores to the hypnotic clanging of pachinko parlors to the festive shouts of a matsuri. Purely as a historical record, the film offers an actual snapshot of a time often reduced to an aesthetic in modern times.

These ground-level shots of the city mix with Sakamoto’s own musings on art in the 1980s (which, with a focus on out-of-time-ness and general fragmentation, seem fitting for modern times too) to create a documentary dealing largely in change. Japan itself wasn’t quite at its economic height yet, similar to how Sakamoto was still navigating his own post-YMO solo career. The shots of him working in the studio to create songs for Ongaku Zukan are ultimately the most engrossing, simply because they find him chasing his creative muses down at a time where he’s not sure what to be, but still very much excited to see what’s possible with traditional and new instrumentation. Everything is in flux — but the desire to create cuts through.

Few Japanese musicians have been well documented as Sakamoto, but nothing has captured his creative process quite like Tokyo Melody, while also offering a context for how his approach changed as Japan itself underwent unprecedented economic shifts. There’s no clear narrative over these 60-plus minutes, but plenty of insight into the mind and times shaping one of Japan’s most beloved creators.