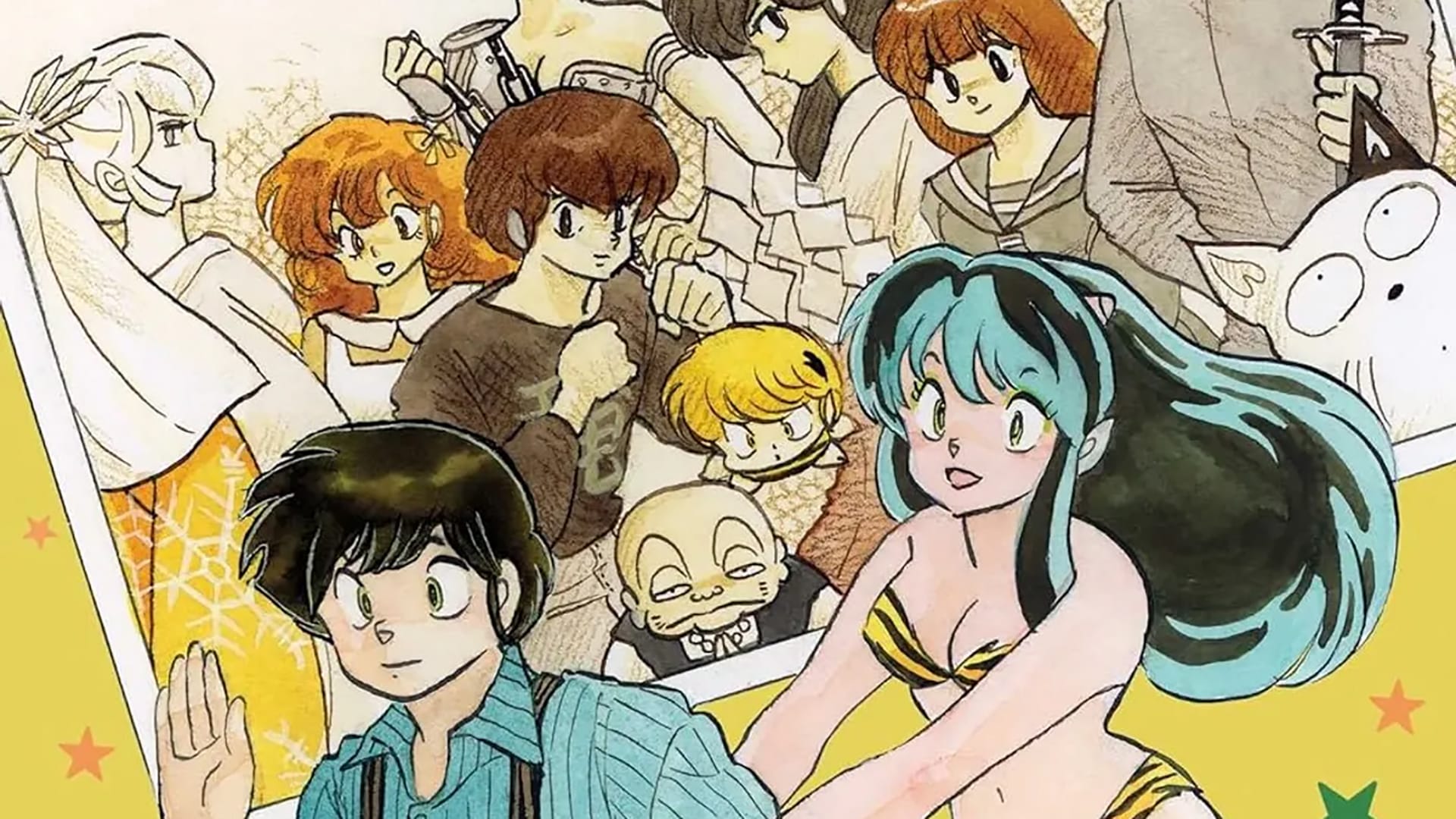

Rumiko Takahashi is one of the most well-known manga artists in Japan. Additionally, with her works reaching a global sales estimate of around 200 million copies sold, she is roughly in the top 50 authors of all time. Her most well known work, Ranma ½, played a significant role in the popularization of anime and manga in the west, and was followed by Inuyasha, which thrived worldwide at the time the anime was released shortly after the turn of the century.

The starting point for her explosive success happened two decades earlier, in 1978, with her breakaway hit, Urusei Yatsura, in which she established her signatures – both in terms of the artistic style for her characters, easily identifiable as her own even at a quick glance, and also her slapstick comedic style, which tends to heavily incorporate cultural puns, superstitions, and over-the-top physical humor that has established tropes that have since been replicated by countless other works. All the while, using both fast-paced action and sentimental romantic themes to appeal to a diverse pool of readers.

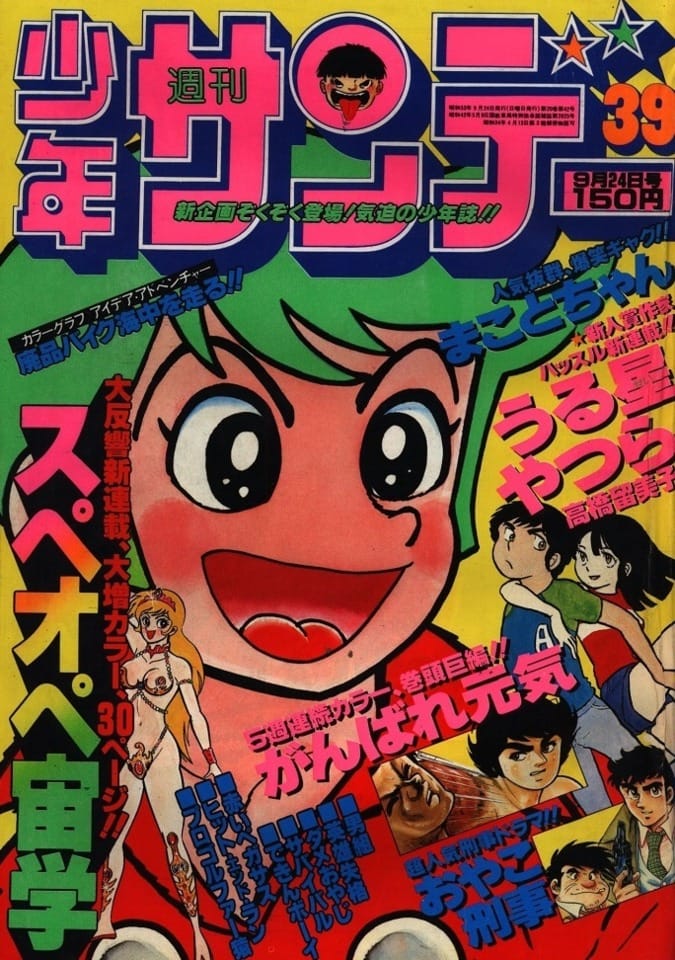

Weekly Shonen Sunday 1978 issue 39 - The Debut of Urusei Yatsura | ©Rumiko Takahashi/Shogakukan

Like many other earlier anime and manga titles, Urusei Yatsura was well known by name to anime and manga buffs around the world, but not necessarily understood or coveted in the west to the same level as Takahashi’s relatively current works initially. However, fans have over the years began to look to the past amicably to learn of the origins of her style, and how it has evolved with experience.

Urusei Yatsura establishes Takahashi’s punny wit with its title alone

One of the challenges of translating a work from Japanese to English is finding appropriately equivalent language in such gags and puns related to language itself aren’t wasted, which is a major reason why Urusei Yatsura was potentially too difficult of an introductory work to Takahashi’s genius for a western society that had yet to be baptized in the knowledge necessary to sufficiently express elements of Japanese language and culture before the mass-popularization of anime and manga.

The title itself is a play on words, with “urusei” being a modified form of “urusai”, which means noisy or annoying. “Urusei” is often used as an interjection in the same way someone might exclaim “shut up!” to express annoyance with another person or group’s nagging or disturbing chatter, for example. “Sei”, however is written with the kanji for star, 星, which is used to mean planet. “Yatsura” is an informal way of referring to a group of people, ie “those guys”. When you put it all together, the title isn’t easily translatable, but essentially means something along the lines of “Those obnoxious/annoying aliens”.

As the west has become more acclimated to anime and manga, it has generally been accepted that the best way to deal with this issue is to simply leave the title Urusei Yatsura as is, untranslated. With Takahashi’s popularity, the title doesn’t need to sell the work; the reader is already equipped with the curiosity to seek out the work, and usually the appropriate level of investment that comes with a desire to dig a little deeper and research the puns, or frequently read cultural notes without them becoming a tedious distraction. The seasoned Rumiko Takahashi fan is undoubtedly accustomed to coming across frequent cultural references, as all of her works tend to be littered with parodies of Japanese culture, and plays on myths and traditions alike.

The concept for Urusei Yatsura went through many evolutions before settling

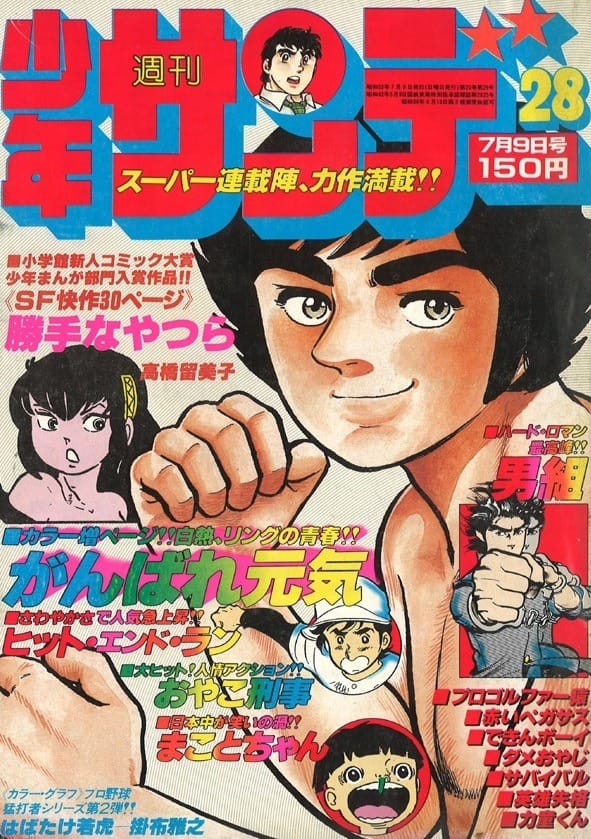

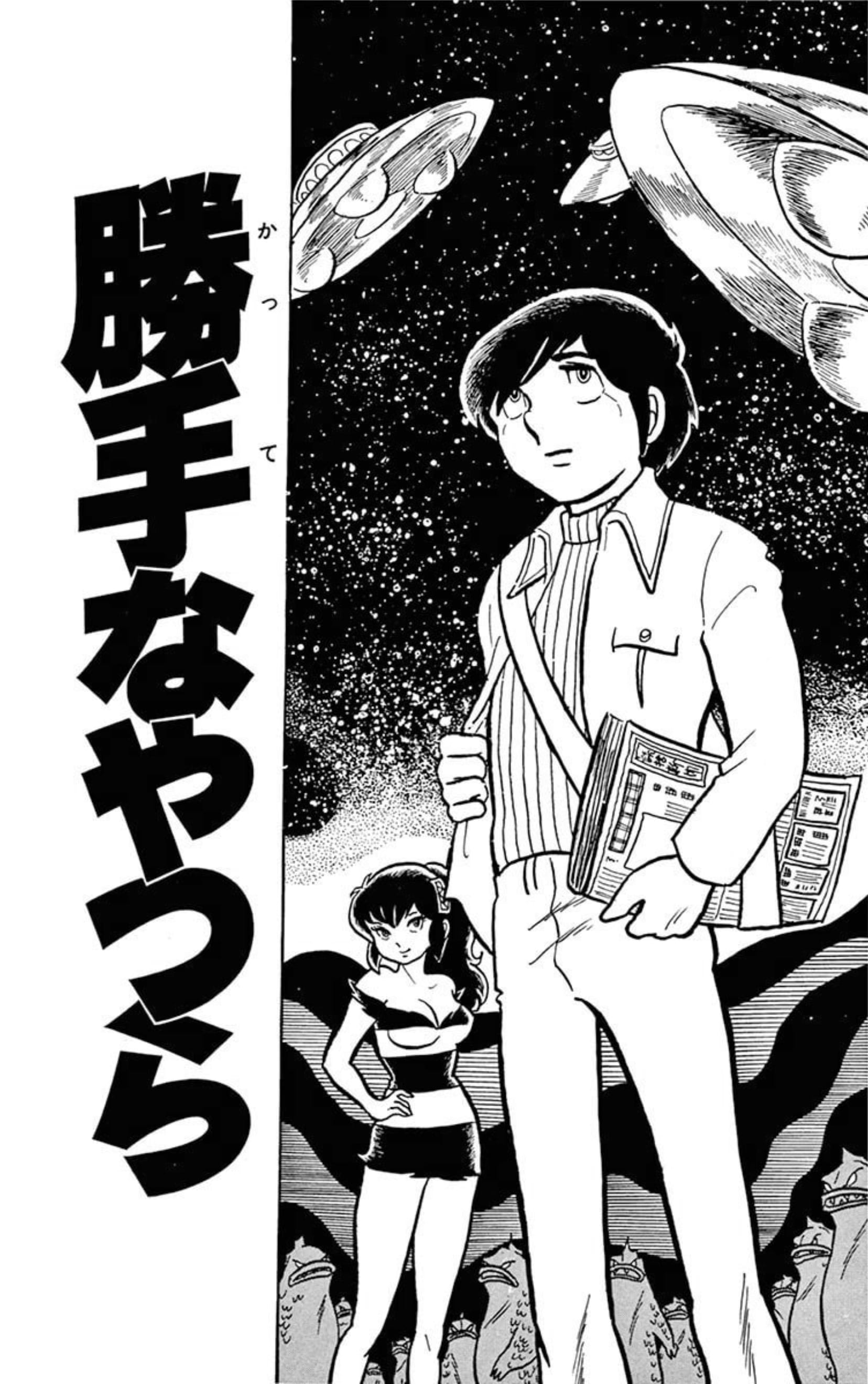

The origin of the series can be traced back to a one-shot manga story and Takahashi's professional debut, Katte na Yatsura, which featured a school-aged boy caught up in a conflict involving a pesky species of aliens. The protagonist, Kei, bears similarities to the character that eventually became the main protagonist of Urusei Yatsura, Ataru.

Weekly Shonen Sunday 1978 issue 28 - Rumiko Takahashi's debut one-shot, Katte na Yatsura | ©Rumiko Takahashi/Shogakukan

Takahashi has stated in interviews that the original plan for the series, which was meant to consist of five different short stories, was to focus on a different “weird” guest character for each chapter that happens to cross paths with Ataru. The first such character introduced is Lum, chosen to represent the invading Oni in a game against Ataru to determine the fate of the planet Earth. The result ends with Ataru’s victory, and an accidental marriage proposal to Lum. Takahashi found herself reintroducing Lum in the 3rd chapter to better fit the story, and realized the character simply worked well. When the series expanded into something larger, the vision was now clear.

The dynamic that occurs between Ataru, Lum, and Ataru’s other love interest Shinobu ended up creating something like a reverse harem style situation affecting multiple characters. Multiple cast members find themselves chasing (or being chased by) other characters that inevitably are caught up in the story, such as Ran, a childhood rival of Lum’s out for revenge, or Sakura, a priestess who joins the staff of Ataru’s high school as nurse, and Shuutarou Mendou, heir to a rich family who transfers in as a student and takes an interest in Lum. The result is a maze of links and triangles between suitors and love interests that makes for potentially limitless conflict.

In the end, Lum became arguably the most important and iconic character, and is even seen as the face of the series, even though the role was intended for Ataru. Furthermore, the situations budding from Lum’s encounter with Ataru became a blueprint for successful comedy and many wacky characters over the course of Takashi’s career, with different future works exploring new takes on the formula.

Urusei Yatsura’s anime spans several seasons, a half-dozen movies, and OVA specials

Starting in 1981 with the Kitty Films anime adaptation, Urusei Yatsura boasts a television series of 194 episodes, spanning four seasons. Some earlier episodes were split into two individual story segments, resulting in a total of 213 stories. Four films were also released over the course of the run, with two following up after the run was finished for a total of 6.

The original anime series has a classic retro aesthetic to it, which depending on the taste of the viewer could be a welcome dose of nostalgia, or feel a bit alien (pun intended). It’s worth at least checking out to get a gist of the original flow and feel of the series for general anime fans looking to gain some historical perspective, and it also makes for an interesting companion piece for fans of Takahashi’s later comedy-romance works, especially Ranma ½ , to compare and contrast – although, both works are several decades old at this point.

A less abrasive entry point, however, would be to look towards the 2022 reboot of the anime with its polished, modern visual style and renewed charm. The new series contains 46 episodes across two seasons, and fits a faster pace that is a great way for a newcomer to experience the series without the potentially discouraging fatigue of hundreds of episodes.

Either way, Urusei Yatsura is a great medium to begin to explore the journey of Rumiko Takahashi’s rise to fame, and experience how her works have evolved over time, and continue to influence and inspire new adaptations many decades later. The success of the reboot of the anime paves the way for both more Urusei Yatsura media in the future, as well as the prospect and demand for more reboots of classic Takahashi works, such as Ranma ½, which is in the process of airing its own reboot.