David Bowie and Takeshi Kitano. Neither were known for their acting prowess in 1984. The earlier had appeared in a few US and European films over the years, and even made an appearance on Broadway, but it was still his singing that people adored most, not his acting. With Kitano, he was a comedian. He was the variety show guy. He wasn’t an actor, he wasn’t a serious film person. So why are both these people playing leading roles in a Japanese film about a British soldier in a concentration camp, produced by one of Japan’s greatest-ever directors, Nagisa Oshima?

Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence is a film that only appears baffling until you see it and understand the man behind the camera. Nagisa Oshima was staunchly anti-war, but focused instead on creating stories about the human spirit persevering in times of war when exploring the topic of World War II, rather than finding it necessary to relive the bloodshed on screen for a grand shot. That’s a big reason why this film takes place in a concentration camp far from the front line as opposed to the battlefield. If even when there’s no bloodshed, the overhanging threat of war is enough to pit these people against each other who could find camaraderie in a place less cruel, why would we allow something so deadly and destructive to exist?

Wouldn’t you want peace?

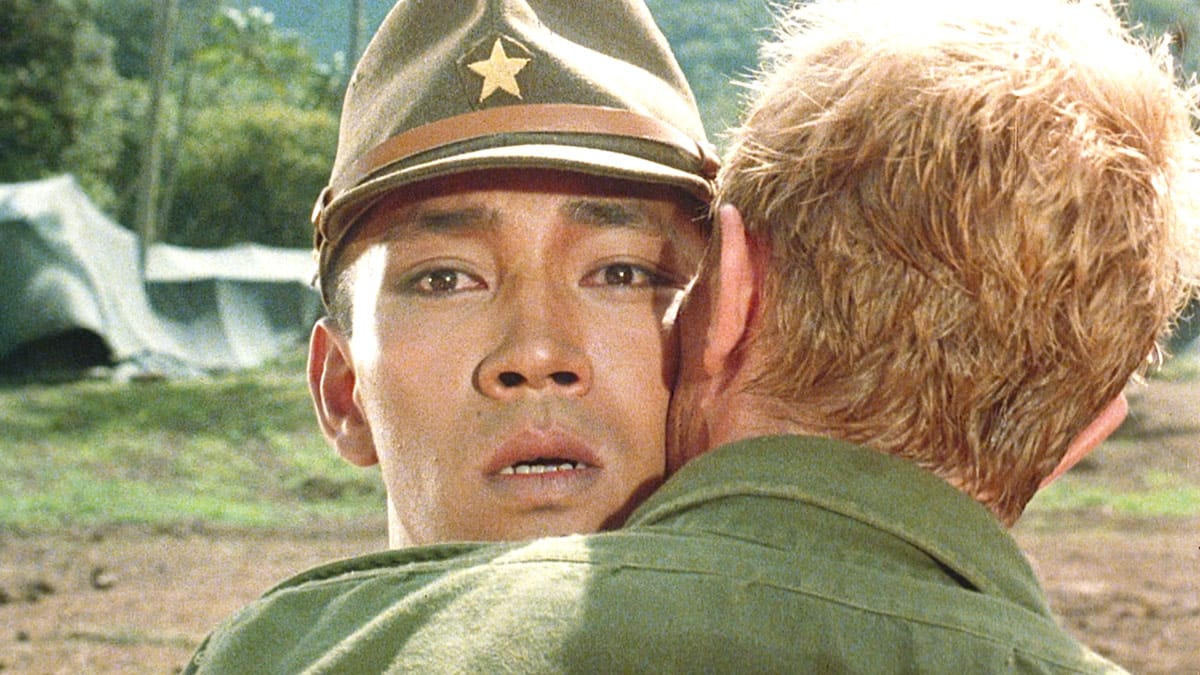

On the Island of Java, a concentration camp run by the Japanese army has been constructed to house prisoners of war. Major Jack Celliers (Bowie) arrives at the camp run by the Captain Yonoi (Ryuichi Sakamoto, the famed musician who also composed the film’s music), and forced into grueling conditions alongside the other prisoners. The only person able to break through the language barrier separating prisoners like Celliers from Yonoi is Lieutenant-Colonel John Lawrence (Tom Conti) thanks to his Japanese knowledge. Nevertheless, Celliers is able to bond somewhat with the superior Sergeant Gengo Hara (Kitano), and perseveres through sheer will to survive in a manner that fascinates the pride-fueled Yonoi.

It’s the tension that fuels the tantalizing core of this film. The pride of Yonoi comes from the feelings of failure from dying on the battlefield with comrades, his punishment an installment running this lowly prison camp far remote from his home. In that, the fact that a man technically lower than a prisoner in his world, holds so much pride in himself and his status and commands such respect, charges their relationship with tinges of jealousy and desire and sexuality. And the question of a sexual tension between these men is something that Oshima is not shy in capturing through how his camerawork at least implies on the unspoken internal processing that Yonoi is facing to his feelings surrounding this unusual man, with no man better suited than Bowie’s status in the era to become a symbol of such longing.

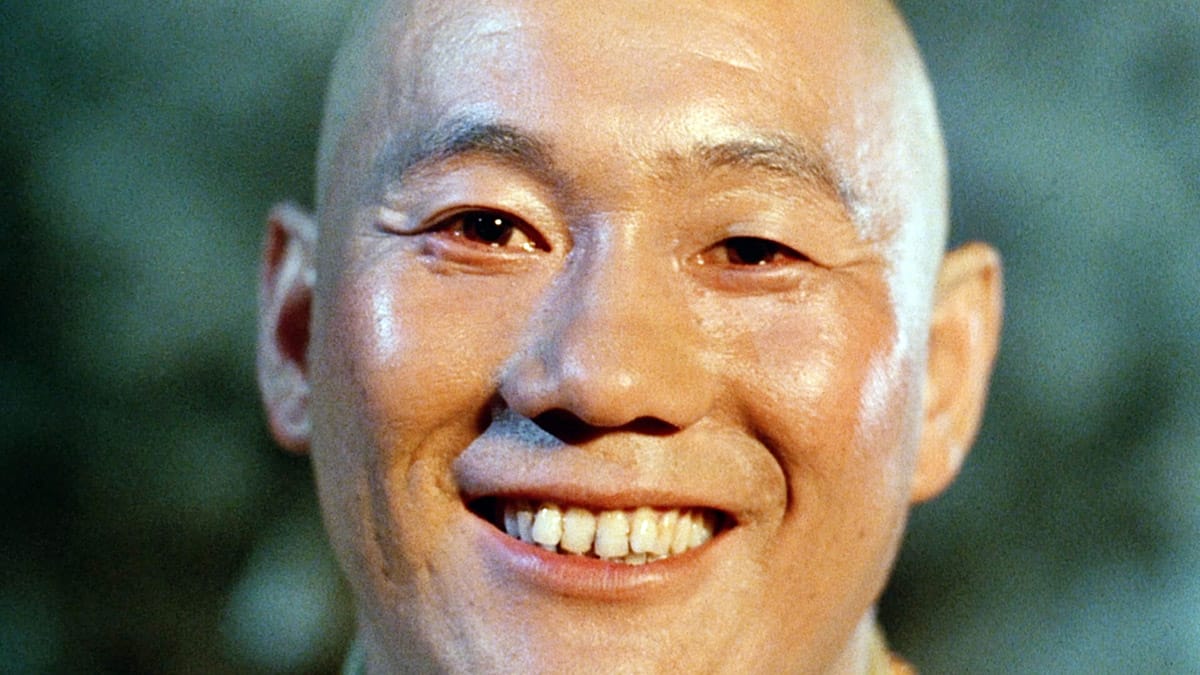

It’s not like Celliers, too, doesn’t feel a sense of regret that fuels a mask he puts on to those in the camp, either. His manifests in a different manner, a sense of not wanting to show a weakness that caused him to act out in the way he once did during his school years. Then there’s the aforementioned Kitano, an almost-ambivalent upper figure who cares little for either of them. He allows Lawrence, the man he’s come to know and at least gain a rapport with, and Celliers to live based on a drunken holiday whim, and his ambivalence is both a blessing for those trapped and a damning statement on how behind his beaming smile is an uncaring, cold embodiment of the war effort.

Nothing is attainable for any of these men, and yet they’re all on this island on sides of a war playing the part of oppressed and oppressor when no one really benefits. Even those in luxury, like the Japanese generals, will ultimately end up losing from this. It’s a fascinating undercurrent of human interaction, historical gravity, callousness and brutality that just works.

Suddenly, Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence's unusual casting makes sense. Ryuichi Sakamoto had already begun his work scoring for films but he was still a member of the mega-popular Yellow Magic Orchestra at the time, a wrinkle of something more to the man that mirrors his character. Only David Bowie, with natural beauty, could allow for the natural pride that shines in his performance to create a tension with some taboo, unspoken sexual charisma.

Then, Takeshi Kitano. Known more for comedy than acting talent, his deadpan humor and natural presence allow him to embody a serious acting role of a benevolent head of the camp easily. Today, he is rightfully known as one of the most talented actors and directors of a generation, but before all this, just the awareness people already had of him would make him a fit for the role. When we first see Kitano, he’s smiling, not quite in contempt but in a place where the events around him don’t matter, which only makes his character all that more engrossing.

Oshima’s filmography always touched on people on the outside, whether that be politically, socially, sexually, and no matter their roles here all these men exist as this whether aware or not. That’s what makes this camp, these characters, so fascinating. The film is beautifully shot, a mix of a camp built on a remote island from scratch for the film despite most remaining unused bringing a sense of foreboding presence to the film, contrasted with flashbacks to Celliers past shot in New Zealand, giving the film a captivating look that, as much as it feels destitute for the prisoners, also feels devoid of a place in our world. That unreality makes these characters both the center of the world, and a notable minor irrelevance whose complex realities mean nothing in the context of war.

It turns a very real story - though not a direct take on a real story, the novel of which it is adapted is based on the notes of a real prisoner of war - into a sort of fantasy that doesn’t negate the realities of the war while fitting at home in Oshima’s filmography. It’s hard to look away from, and it’s precisely this that allows its taboo and the questions of their purpose and desires ring more powerfully.

Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence is one of the earlier examples of an international co-production that has only become more common in recent years, but this is a case where such international connections create something that could only be born from such cross-border relations. An irony considering the movie in question. It’s admittedly one of his more mainstream affairs, but it’s an embrace of this without forgoing his political and socially-astute leanings that make this film feel just as potent as any other in his filmography. It’s the place to start with Oshima’s work, for sure, but also, perhaps his best work in the process.