The reverence of Japanese cuisine continues to persist and evolve in the age of mass media across television, social media, and film. Luxury Japanese food has been glorified for a long time and rivals any top quality dish from Italy, France, and China. Casual, everyday offerings like sushi, ramen, and matcha have become a mainstay part of the glutinous American diet in the same way pizza and tacos have.

Ramen has become a staple food synonymous with Japanese cuisine in particular. From the cheap instant ramen packs and cups in grocery stores to the freshly made ramen dishes at a local Japanese restaurant, the dish has a special place in the hearts and stomachs of every North American for its tastes and affordable value.

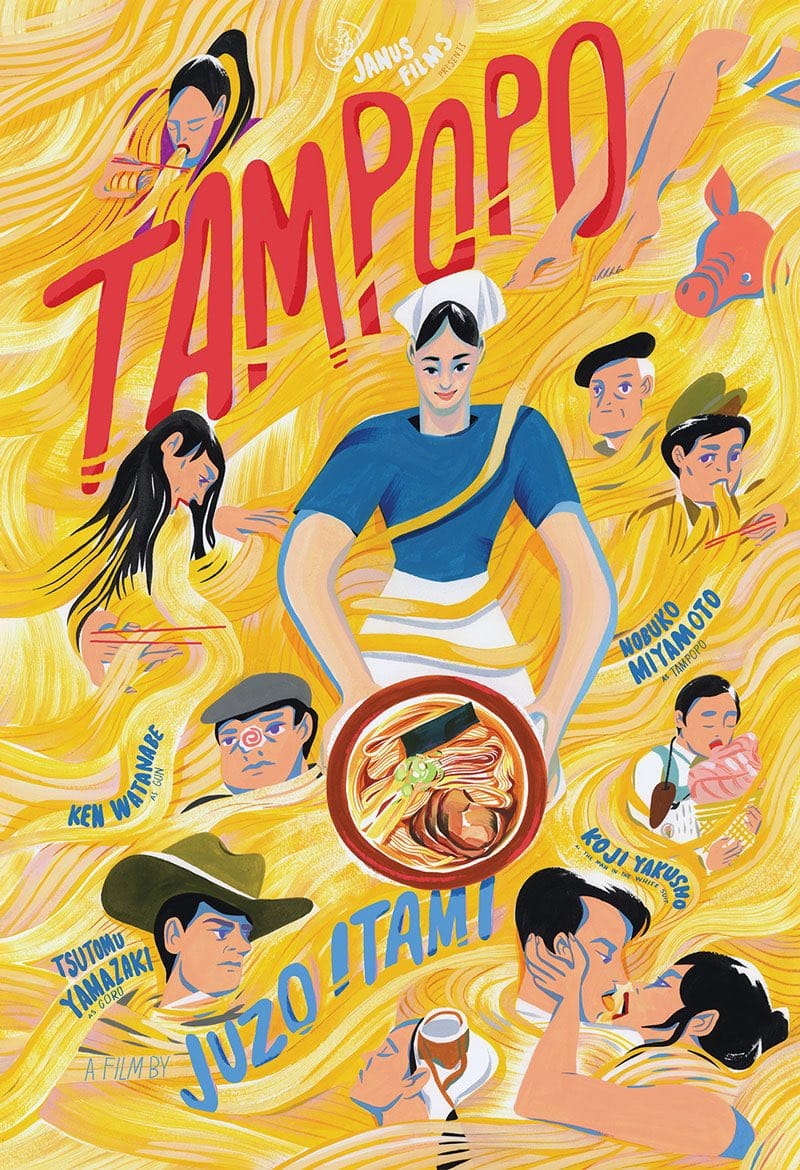

It’s this fascination with ramen that I was drawn to watching Juzo Itami’s 1985 film Tampopo for the very first time — a well-regarded film among cinephiles who have heaped praise for its exceptional shots, framing, and editing, as well as its light-hearted comedic tones centered on food. Because of this, the film has often been categorized as a “ramen western” by the Criterion Collection, which is a play-on-words of the spaghetti Western film subgenre that feature cowboys being directed by Italians. It’s an odd marker to have for a film, but after watching it from beginning to end, it’s a very apt descriptor.

Tampopo’s anchoring story follows two roaming truckers named Goro and Gun (played by Tsutomu Yamazaki and Ken Watanabe), who decide to have a bowl of ramen at an unassuming restaurant one rainy night. The small place is run by the eponymous Tampopo (played by Nobuko Miyamoto), who is a single mother struggling to make good ramen that draws people in. Wanting to turn her business around, she enlists the help of the cowboy-hat wearing Goro to improve her cooking skills, craft a delicious ramen recipe, and learn effective techniques to kickstart her restaurant’s success.

Much of the main characters are memorable and have great impact with their on-screen presences. Particularly, the side cast features some colorful personalities that include the professional chef Shohei, the enemy-turned-friend and contractor Pisuken, and the unnamed ramen master, who is first introduced as a wise homeless person that serves as the film’s Yoda-like figure. Goro also forms an unlikely friendship with Pisuken, who were at each other’s throats when they first meet, following the latter’s argument with Tampopo on closing down her business. After engaging in a tense brawl, the two find common ground to help Tampopo’s business together.

Goro's camaraderie with Pisuken and his dynamic with Tampopo best exemplifies the beats of the Western genre. We’re shown an outsider who is roped into a new environment and finds themselves becoming a savior to a town or person. This is the central conflict driving the film, where we’re shown a group of strangers and allies uniting to help a person’s cause.

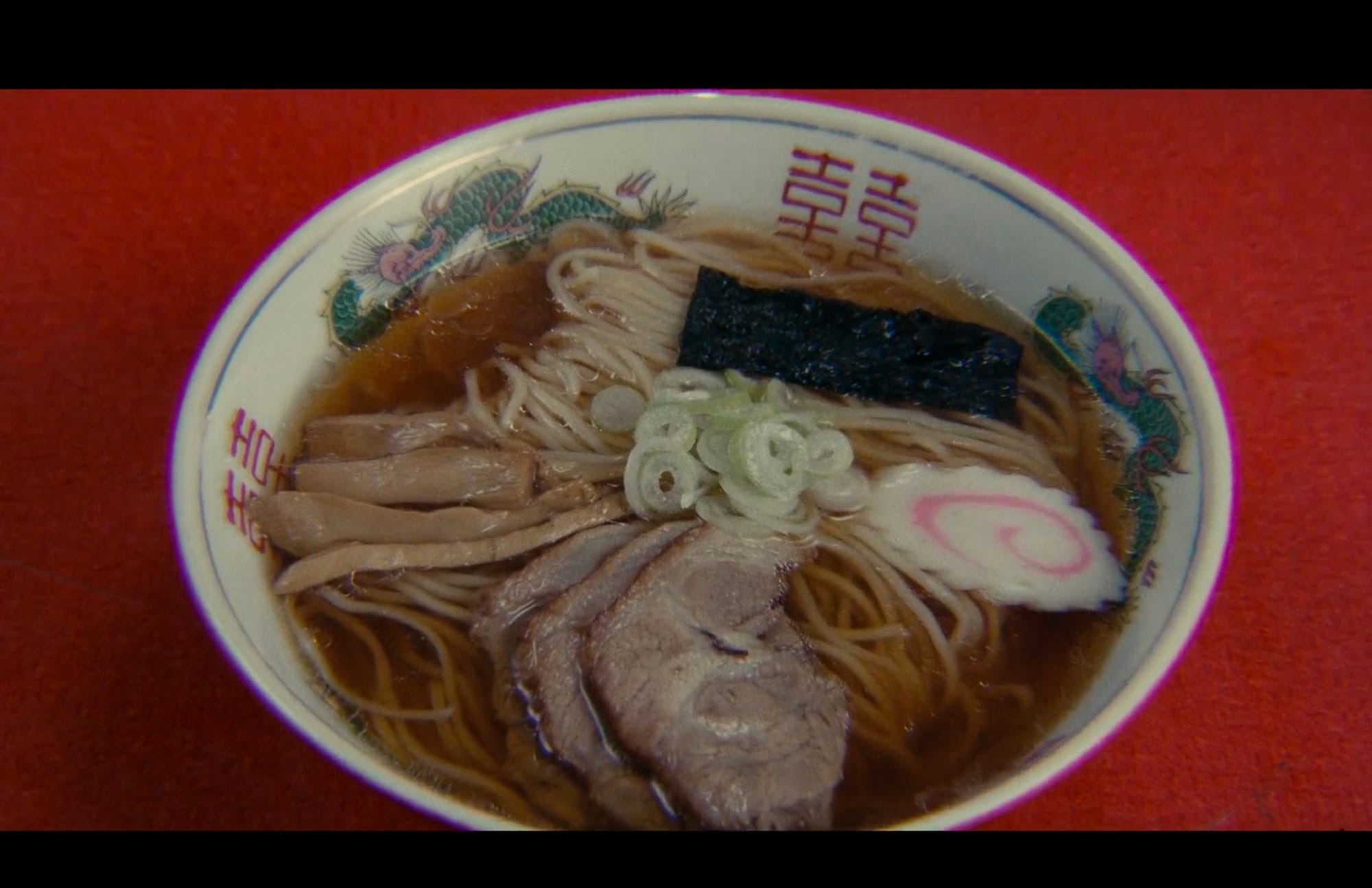

However, as much as Tampopo’s homages to the Western are clear, the core theme of the film is food. The process of making proper ramen is explored in great detail, as well as the general etiquette of eating and serving it. The cooking scenes showcase not only the beauty of the food being shot, but also the precise techniques into making and plating them. Behind-the-scenes, I learned they had a special person appointed to craft the food for the film to make sure it’s well-done and accurate, which is a good touch in the production.

One of the equally most important features of Tampopo are the loosely connected vignettes intercut throughout the film, making it as much a comedy as it is a food movie.

Some of my favorite random moments include:

- A women's etiquette class learns to eat food quietly, but is suddenly upstaged by a foreigner slurping his food loudly,

- An underling salaryman perfectly orders from a fine dining Western restaurant and going against the grain of his superiors.

- A crook tries to rip someone off during a fine meal, but the victim himself is a thief who’s caught before he can take the wallet and enjoy his meal.

- A dying mother cooks one final meal for her family as she’s about to pass away. Afterwards, the family vows to finish her meal together to remember her.

- A man has a tooth removed and, afterwards, shares a vanilla soft serve ice cream with a child who’s not allowed to have sweets.

The comedic bits can range from feeling surreal to showcasing physical gags, as well as setting up and playing with your expectations. They’re seemingly unrelated to the plot, but still play an important role in exploring our relationship with food and why we eat.

Returning to the main story, we see Tampopo, Goro, and friends try to figure out how to improve her ramen and its broth. Goro believed Tampopo’s ramen was okay, but it felt too standard and lacked depth and character. Shohei, Pisuken, and the ramen master agree. Afterwards, they guide her to crafting a delicious bowl of ramen by visiting other ramen restaurants and observing what she can take, learn, and avoid from her competitors.

Scenes like this show us why making good food is a generally time-consuming task and how it takes real dedication and patience to master, as well as an ingenuity to learn from others. It’s a long process that’s made all the more satisfying when Tampopo finally draws up the perfect bowl of ramen, leaving Goro and everyone else emptying their bowls in comfortable silence.

Tampopo and Goro’s story ends when the former has her ramen restaurant renovated and receives a clean uniform to serve her customers. With a delicious new ramen recipe and a motivated mindset, she prepares to serve . Like a classic Western, Goro bids her farewell and drives off into the sunset in glory, having become her personal hero.

Tampopo is a classic film for any foodie or cinephile interested in a well-told story with strong comedic beats and an adventurous narrative. The attention to detail on the ramen-making process and the psychology of running a restaurant makes it a fascinating watch for anyone involved in those fields. Regarded as a unique “ramen Western” film, anyone with a sense of culinary curiosity and appreciation for good food will find this film as enjoyable as any hot bowl of ramen.