Better to have a clean conscious, right? Or do you think you can get away with it?

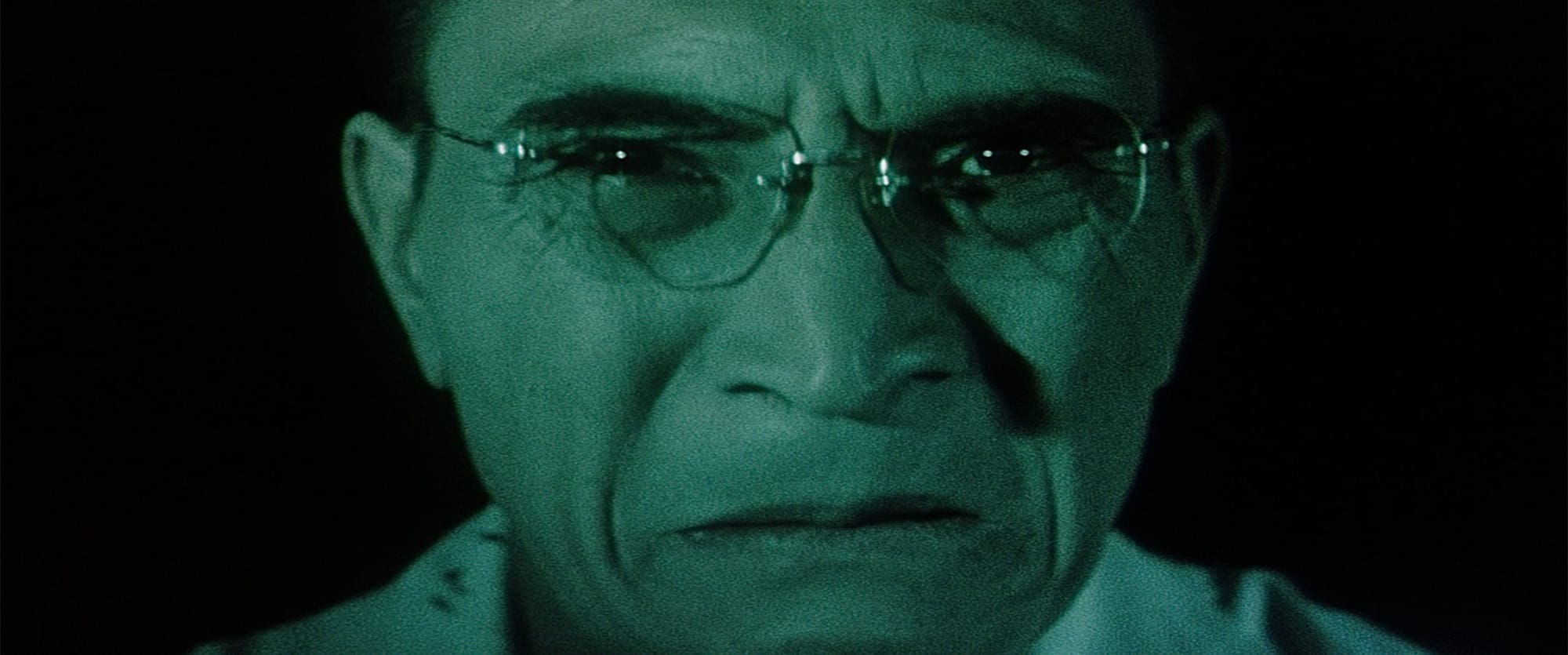

Jigoku by Nobuo Nakagawa is perhaps one of the better-known early post-war Japanese horror films, unnerving in its exploration of guilt and consequence with surprising verocity through a Buddhist religious viewpoint. It’s not just that the film is unrelenting about its portrayal of the agonies of sin, distorting the mortal world into an afterlife almost beyond comprehension, but it shows the temptation that exists to fall into it in near-nihilistic, inevitable turns. It’s theatrical in its portrayal of hell, but also in the survivalist acts that doom someone to this end, leaving the dread of what’s beyond the camera’s view intact.

Beyond the unnerving glimpse peering into hell that occupies its opening, the characters we first meet seem to have no inclination of the fate they will soon meet. Shiro is a young student betrothed to the daughter of their professor, with Tamura the somewhat-reckless friend. While Shiro is certainly the more morally-sound of the pair, when Tamura kills a drunk yakuza member in a hit-and-run, implicating his friend in the crime without the conscience to admit his guilt to the police, specters of life and death begin to haunt them.

The initial sin is clear here: Tamura killed a man and chose to protect himself over being honest and coming forward about his crimes. While Shiro does want to hand himself in, feeling the weight of guilt upon him, he ultimately doesn’t after being convinced it’s for the best to stay out of it. This is their mistake. Sin doesn’t discriminate, damning both and those seeking revenge or acting out in its aftermath equally, leaving all damned to face the punishment beyond life's end.

While Japanese cinema was entering a period of experimental cinema inspired by movements in France and beyond in the 1960s, mirroring the turbulent politics of the era, it’s fair to say that Nakagawa’s work here was an exception even by the standards of this unprecedented era. The film coming from a niche genre-driven studio like Shintoho, formed from a split with Toho proper following union strikes in the 1940s, certainly factored into the unusual production. Even before Jigoku, the studio’s work often more-explicitly dove into concepts of social morality and politics than contemporaries were often willing to venture.

In blending traditional yokai and ghost stories and well-known traditional plays into a modern context, alongside Nakagawa's willingness to partially self-fund this venture alongside the studio, it allowed the creator to expand his imagery, attempting to understand what lay beyond death.

Through the lens of sin, Jigoku uses its characters as a vessal to comprehend what could be beyond life. Shiro is a reluctant passenger on the trip to hell, but one whose role in this murder has left him traveling on nonetheless. He chooses to make the trip to the police to confess with his partner, but he never steps foot into the station to admit his crime. Before he makes it there, the taxi he travels in careers off a cliff, killing his girlfriend in the process. Life on this mortal plain soon comes to represent a vision of hell on Earth when his guilty conscious becomes swarmed with other sinners and the mirror image of his dead lover. Tamura finds him in this state, but so too do the relatives of the dead yakuza, very much aware of the pair’s complicity in the crime.

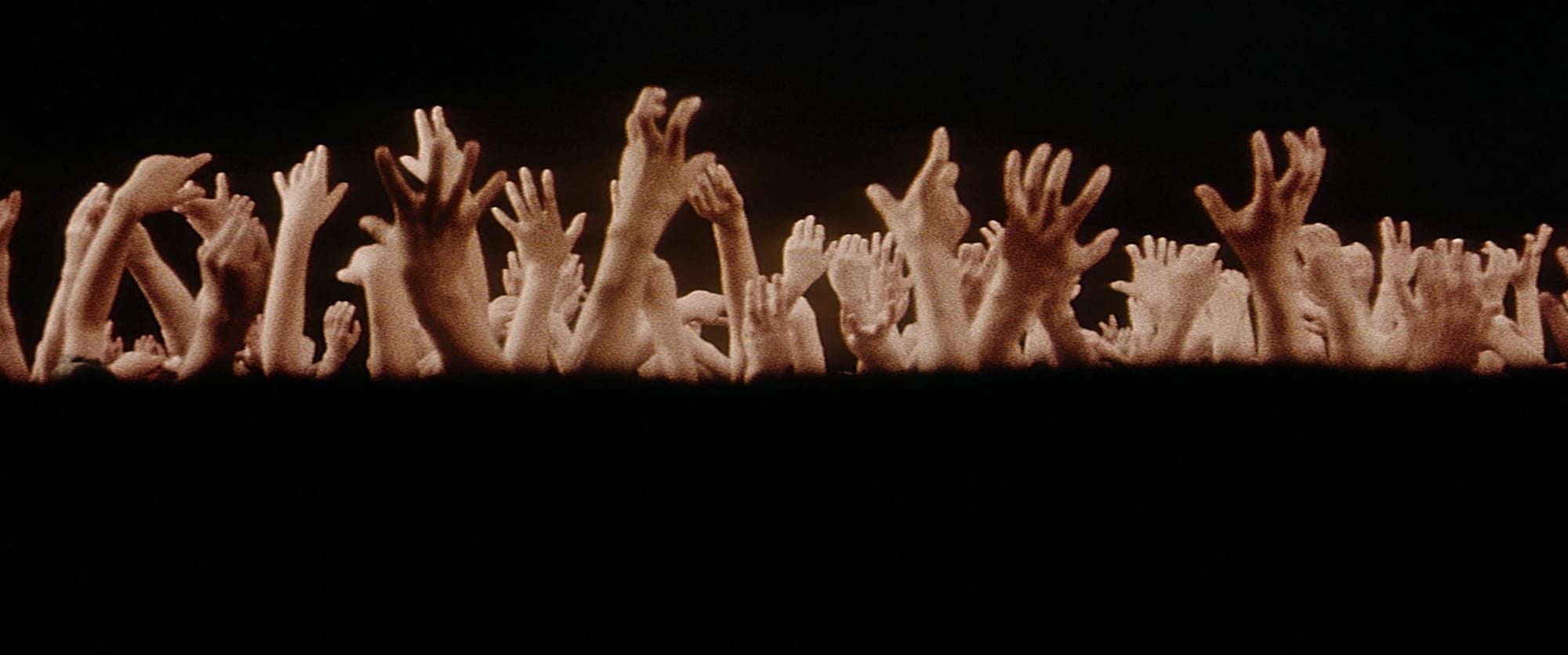

Before long, all are dead, from accidents portrayed at an incessant pace to an almost-comical extreme. Whether through murder or the desire for revenge, all parties shared guilt and sin, and their final resting spot is the same: the depths of hell itself. It’s this second half of the story in the space beyond where Jigoku, in death, truly comes alive. Hell is far beyond typical comprehension, the rules of our existence not applying in this distorted, cruel, fiery new reality. The imagery here lends itself to Nakagawa’s experience in horror cinema with films like Black Cat Mansion, using crude special effects to create unholy imagery that haunt long after the film ends.

Each scene feels more like an abstract painting as hands reach out of the ground to pull the lost souls further into its clutches, skinned corpses cry for mercy and demons beat away the doomed ghosts that continue to wander these planes long after losing their identity. Perhaps most horrifying of all, a single crying baby haunts these blood-stained rivers, a single living being in this land of the dead that at least gives the soul of Shiro something to reach out for amidst such barbarity.

It’s disturbing, but it’s almost impossible to look away from. Even if these effects, essentially prototypes to ideas that would still look crude nearly two decades later in Nobuhiko Obayashi’s House, are far from believable, the ideas they convey are enough to send a shiver as this inevitable endpoint of sin sears into the soul. It’s shockingly visceral, even while looking admittedly aged, simply because so few films are this twisted and extreme in depicting hell.

It’s easy to wonder what the point of this all is. Shiro felt guilt and repentance for his actions, but still ultimately went to hell and faced unspeakable things in the process. Everyone did. It would be easy to say this is merely a horror director taking the genre to the extremes, but there’s more to it than that. Within each of the horrors portrayed is something undeniably human. Whether it’s the hands reaching from the grounds of hell itself or the baby floating down the river, these are horrors rooted in the human experience taken to the inhuman ends. Hell in Jigoku is not just a place of sin some souls end up after death, it’s a place both shaped by the deepest fears of humanity and twisted far beyond.

Even then, so much of hell is shrouded in darkness, because as much as the Buddhist belief system speaks of such a place, there is no way to know what lies beyond. That’s the biggest terror of Jigoku. Even if we could see the place, we could never fully comprehend such a thing, and it will never be possible to truly understand what lies beyond. Maybe that makes the whole film an exercise in nihilism on death’s inevitability and damnation. Or maybe it’s a reminder of what can be offered in life before we reach that point, and what should be held onto while it still exists.

scrmbl's Classic Film Showcase shines a light on historical Japanese cinema. You can check out the full archive of the column over on Letterboxd.