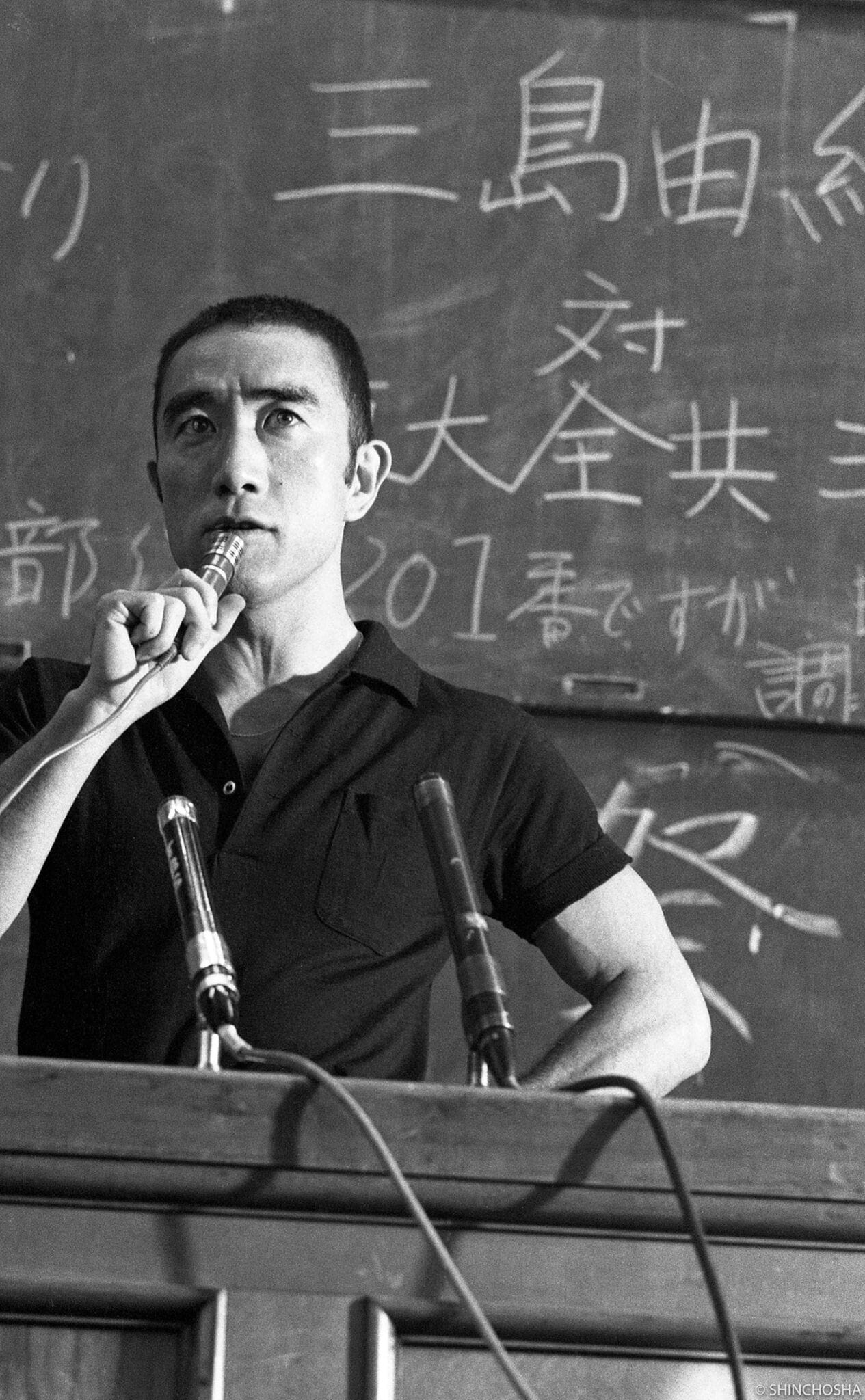

At the recent Tokyo International Film Festival, the 40-year-old festival screened Paul Schrader’s Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters. Why not? For all his controversies, Yukio Mishima is one of the most notable political and literary figures of the last century, and the film is celebrating its 40th anniversary in 2025. Thing is, there’s far more to this screening than just the commemoration of the 100th anniversary of his birth, as the film made its Japan premiere decades following its original release in a sea change for how the country has been able to look back on this enigmatic, controversial figure.

The film is a biopic of-sorts, blending reality and the fiction of Mishima's work into an all-encompassing tale of what a man generally regarded as one of the the 20th century's most talented writers, alongside its most unusual. The film takes place on November 25th 1970, Mishima's final day as he publicly committed suicide following his failed coup attempt while offering extended flashbacks that shed light on a life of literary creation, homosexual ideation and radicalization. This was both an artist and a general of his own private army, his final acts as much an art piece as his many creations. Intolerance as intriguing as it is repulsive, all masking a traumatized soul, he’s the perfect figure for a theatrical exploration.

This was created by Schrader at the peak of his cultural relevancy, fresh off work on Cat People and American Gigolo that gave him the cache to convince a American producers to partner with Japanese actors to spend millions on an arthouse retelling of a figure relatively unknown in the US, entirely in Japanese. The film's intended largest market was Japan just as much as the US, though no-one in this country ever got the chance to see it. Set for a premiere at the 1985 Tokyo International Film Festival, orchestrated right-wing protests from those who viewed Mishima with reverence and disliked this portrayal pressured the festival to canceling the screening. Future theatrical releases via Toho were also canceled, with no streaming or home video release coming to pass.

Plenty of import stores stock US copies of the film today, but the story had never been officially screened and released in Japan until this timely return to the festival that once disavowed it.

Schrader was even in attendance for this long-overdue event! The screening was not just a chance to write the film’s prior absence after a ‘multi-year process’ to bring the film back to Tokyo, according to festival organizers, but a chance to use the event as an initial avenue to try and understand the man’s place in Japanese history all these years later. It was the big-ticket film of the festival, screening as part of a broader program that included documentaries about his final public debate and more.

Mishima was born in 1925, spending his early years with his grandmother sheltered from the outside world. It was after returning to his real parents at the age of 12 that an extreme parenting style from a militant father that disavowed his interest in literature shaped him to the person he would become. Mishima would still write, but with only his mother witness to his work, learning of theater and traditional Noh and Kabuki in particular during these years and forming an obsessive interest.

Across his career he would be nominated multiple times for the Nobel Prize in Literature, working on books, plays and films that collectively number into the hundreds. His writing came to embody somewhat of a contradiction that dominated his writing and ideology. This was a man of extreme nationalistic and traditionalist far-right beliefs, a devout follower of Shintoism and the spiritual power of the Japanese and particular the deified Emperor. Yet the man he devoted the most adoration to was himself, transforming his body into an art piece and embodiment of his ideology through bodybuilding and the aforementioned building of his private army. Before long, the Mishima the public knew was no longer a man but a physical embodiment of his work, dedicated to transforming national identity and vying for a return to traditionalist policies and spiritualist belief.

Fascist politics and imagery replaced any sense of a real Mishima, once a scrawny youth whose writing as much dove into complex homosexual urges enacted in real life with male lovers, as much as it touched on politics and power. Unsurprisingly, even this aspect of the man is unclear in the facade Mishima would create: was his queerness a love for the ideal masculine identity? A vanity project that saw him transform his soul and engage in acts of gay sex, taking on private, violently-physical encounters?

Yukio Mishima is an enigma embracing and contradicting the order he wished to return to, a man that, 55 years since his death, is impossible to compartmentalize. It’s what makes his art as intriguing as it is horrific. Today, his words on a militarized, revitalized, return-to-imperialism Japan resonate with the hardened far-right seeking a closed, mono-nationalist state. To them, his reverence to the samurai and seppuku speak loudly through their work, and this adoration to a culture of the past unsullied by Western influence is a particular appeal. As long as you avoid all the gay sex and homoeroticism he engaged in that those same people find abhorrent.

When Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters was set to premiere at the Tokyo International Film Festival 40 years prior, portrayal of Mishima's sexuality was a major factor in the uproar. Here was a foreigner in Schrader, creating a movie about ‘their’ Mishima, showing to the world not just his ideology but his complexities and everything they liked to overlook. This film was set to screen just 15 years on from his death, at a time when the nation was still trying to understand a legacy tainted by attempts to overthrow the democratic laws of the country. So severe was the political backlash to the plans by the festival that the screening was canceled.

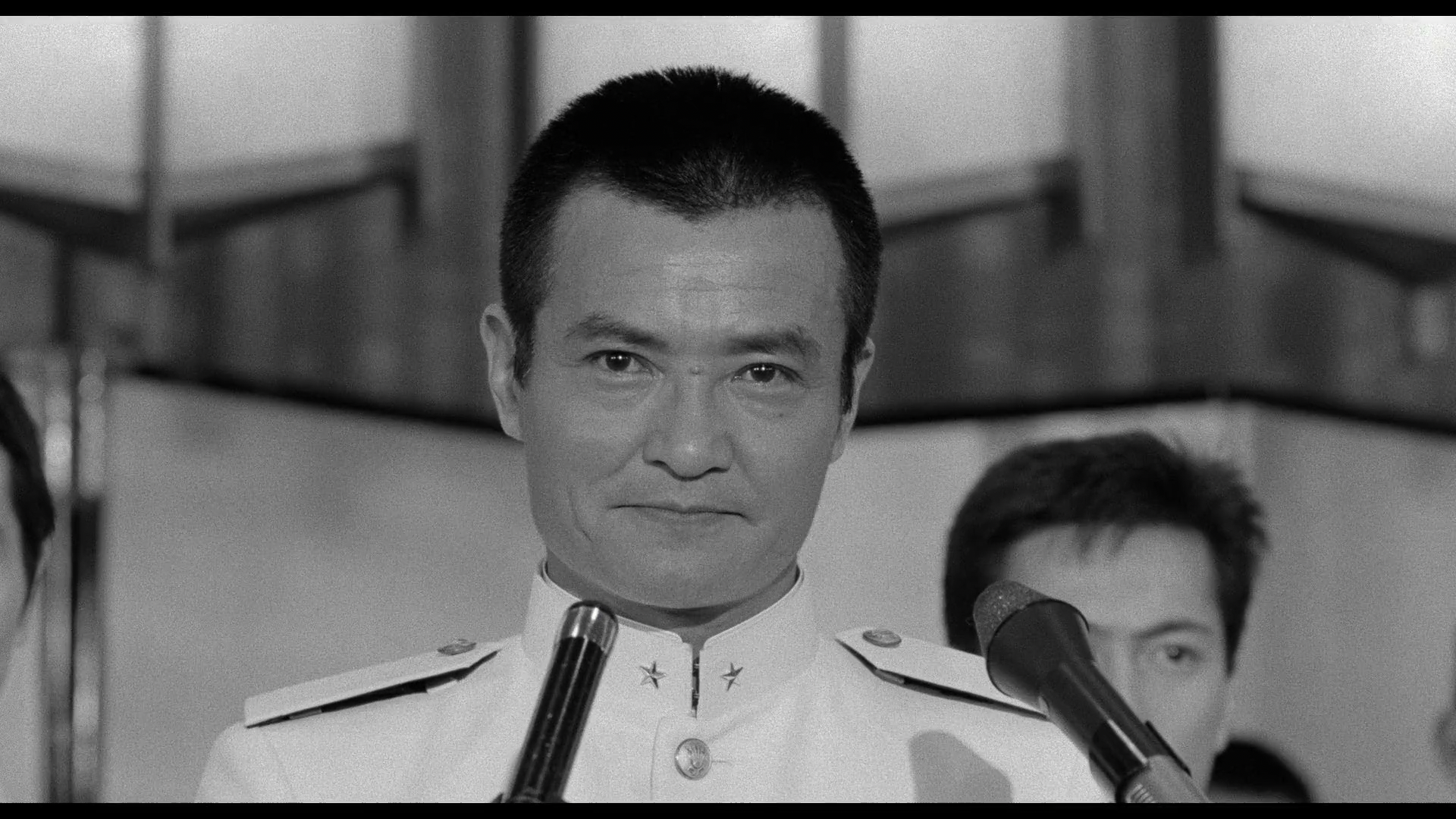

Which is ironic, considering Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters was not only made with limited approval from the estate, but by a director who genuinely respected the artist and created a film that embodied everything he was in all his flaws and talent. The film uses that infamous 1970 attempted coup as a framing device to look back on the man’s life and his work. When the film returns to Mishima’s youth and his younger days, the film resorts to a black-and-white image that scrubs the world of all but his direct surroundings and core influences. A few key works, such as Temple of the Golden Pavilion, scream to the surface in full theatrical color and play out as-written. These are mirrors of Mishima's real life, playing as an attempt to understand the man below the artifice and theatrics.

The film, one that becomes increasingly-abstract as it dives into Mishima’s imagination and ideology to the point the real and fantasy, like the man himself, merge into one, is the ultimate champion of Mishima's problematic expressionism. The goal of Schrader’s production was to not just observe that real and fiction had merged into one when it came to this man's art, but that he explicitly merged the two till no truth, only ideology, remained. By the time he enters the military compound, Mishima the artist is all that enters the building.

Schrader draws direct parallels to Mishima's 1966 film Patriotism, where he ends this wordless ode to authority by committing seppuku. By this point of his career, militarism and the final death were not just a theme but an obsession. When words are fleeting and actions feel momentary, only a permanent end can be eternal.

This observation re-contextualizes his final act. When we finally witness him undertake his own suicide, we’re left pondering a fascinating dilemma. Did he ever see a coup as a viable goal? He went with just four other members of his large private army to speak to a single battalion, knowing media would attend. To commit seppuku on his inevitable failure mirrors Patriotism almost directly. While the dramatization of Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters inevitably makes the imagery of this film more closely mirror between the two works, the parallels are undeniable.

His unlikely attempt to use a speech to rally the army into restoring a traditional spiritual power to the emperor, only to die in a déjà vu-esque final act, is nothing if not poetic.

And this suicide is now an inexorable aspect of his legacy! Mishima’s ideas, art and death will never be separated, and they’ve arguably persevered over the years by taking his ideology (true or fascist cosplay) further than the far-right idealogues who idolize him would ever be brave enough to attempt themselves. It’s not that these acts or ideas should be revered or respected, but as an artist turning life into a performance, it’s no wonder someone like Schrader would view him an interesting-enough character to document on film. In doing so, it ponders how, even after going to such extremes, whether even his beliefs were just a part of some elaborate creative project.

At this Tokyo International Film Festival screening of Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters decades in the making, Schrader made a simple observation. “I knew that this moment would come, I just didn’t know whether I would be alive to see it.” The backlash to this belated screening was far less eventful than those 1980s protests, but that doesn't make its long-overdue appearance any less impactful.