In the world of design, it’s safe to say that no two regions harbour as much mutual affinity as Japan and Scandinavia.

Between an affection for functionality and craftsmanship, thoughtful deployment of detail and sparsity, and a mutual understanding that less is almost always more, the two cultures have developed a deeply reciprocal exchange of influence over the course of the last century.

For Japanese designer Akira Minagawa, a trip to Finland at age 19 would become the inflection point of his creative life.

Having arrived in Helsinki in the middle of winter, Minagawa travelled north to Rovaniemi, a city in Lapland close to the arctic circle. Discovering a coat with which he immediately fell in love, Minagawa spent three quarters of his entire travel budget on its purchase. Upon returning to his Hotel, the owner treated the cash-strapped traveller to a meal and drinks at the bar, a gesture that left a lasting impact— This episode would become the origin for both his love of fashion and deep respect for Finnish culture.

Returning to Japan, Minagawa took a job in a fish market to support himself while studying Dressmaking at Shinjuku’s Bunka Fashion College. He founded minä (Finnish for ‘I’) in 1995, envisioning a brand that would combine his love for Finland and colorful, technique-centric textile design.

In 2000, their first store was established in Tokyo’s Shirokanedai, and in 2003 the brand’s name was amended with ‘perhonen’ (Finnish for ‘butterfly’) to coincide with its London Fashion Week debut. Over the last three decades, the brand has cemented itself as a mainstay of the Japanese fashion landscape while remaining true to its heartfelt, playful approach.

With minä perhonen reaching its 30th anniversary, Setagaya Art Museum’s landmark retrospective seeks to celebrate the brand’s history and Minagawa’s vision, inviting visitors behind the scenes of the creative process. As Minagawa readies himself to pass the torch to the next generation, “Tsugu” (meaning “to connect” or “to inherit”) asks what’s next for the beloved brand.

This was my first time visiting the Setagaya art museum, which is deserving of note for its architecture alone. Sitting at the northern end of Setagaya’s Kinuta park, The cast-concrete structure feels like a strange cross between a Factory and Palace. While the curved, corrugated roofs recall warehouses and industrial facilities, its grand corridors and sunken courtyards give it a level of elegance befitting a royal court, or perhaps a mayan temple. Opened in 1986, it was designed by architect Shōzō Uchii, known for his concrete-forward aesthetic, as well as his academic expertise on the work of Frank Lloyd Wright— an influence that certainly shines through in the design of the museum.

Photo: Caleb Woodward

Long, concrete corridors are flanked by triangular pillars and lined with dazzle-pattern carpets, narrow corridors disappear into geometric shafts of shadow, and corrugated metal roofs arc over the galleries— at first blush, it seems like no greater incongruity could be made between such an imposing structure and the warm-hearted, innocent tone of Minagawa’s work. That is to say— it’s a perfect match. This kind of darkness has always lurked at the edges of the Scandinavian fantasy: the gloaming shadows of unknown spirits among the endless pine-trees, mysterious voices in the night, strangers lurking just outside the warmth of home. This lightness exists not in ignorance of the dark, but in answer to it.

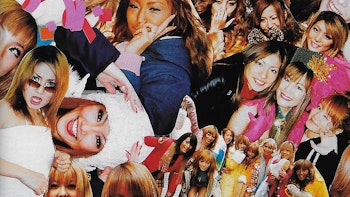

The exhibition itself is framed around five sections inspired by musical terms: Chorus, Score, Ensemble, Voice and Remix. Exiting a long corridor into a circular chamber, you are first presented with a panoramic display of over 180 textiles floating on panels against the curved marble walls. This is the ‘chorus’, a display that surrounds the viewer with the breadth and depth of Minagawa’s work. As impressive as it is, it represents only a fraction of the brand’s oeuvre: to date, they have crafted over 1,000 unique textile designs. Floating above the panels are fabric spheres swinging slowly in the currents of air conditioning, each one embroidered with a different iteration of the brand’s iconic butterfly motif.

Between the stroboscopic meshes of dots and circles, placid forest scenes, and endlessly repetitive blocks of floral pattern, the impression is overwhelming. Your eye lands on a new surface of dazzling pattern and colour each time it drifts from one panel to another. I could probably have spent an hour in this gallery alone.

Next is ‘score’, the largest room in the exhibition. Soundtracked by the distant, rhythmic tones of industrial looms and embroidery machines, long reams of fabric drape low from the ceiling and land flat on long tables before the viewer. This display follows the development of a textile from initial explorations, collages and loose sketches, through phases of experimentation and iteration until the final result, which serves as the backdrop for each table. I was really endeared by how loosely and earnestly Minagawa’s ideation takes shape— plain drawings and cut-paper collages capture a straightforward approach earned through a lifetime of knowledge and clarity of vision.

This section’s title frames the design process as a ‘score’ for the textile’s manufacture and transformation. Like penning the score for an orchestra, the designer sets on paper a series of instructions for a system of disparate parts that work in tandem to produce a united whole. This process is then repeated for the duration of each textile’s production, the collaboration of hundreds of workers and massive, impossibly complex machines.

One work in this section that left me with a lasting impression was “sleeping flower”, from a/w 2021-22. What look at first to be blots of dark green military camouflage are actually fabric patches that can be cut open to reveal sprigs of small, white flowers sleeping underneath. According to Minagawa, the design was inspired by a memory of Marc Riboud’s renowned photograph “Jan Rose Kasimir Facing the Pentagon and Guns”, first published in 1967, the year Minagawa was born.

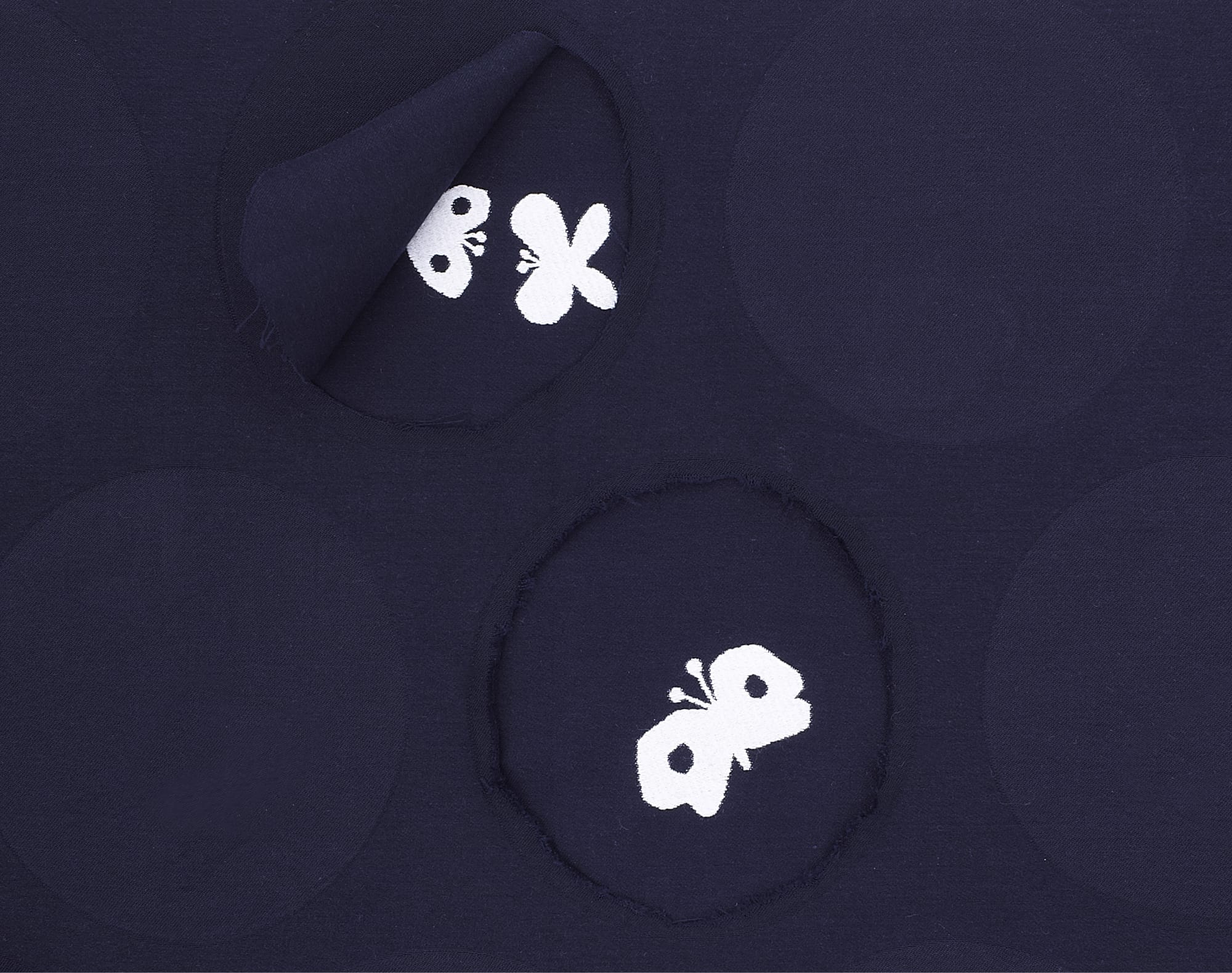

In the photograph, a woman inserts a white flower into the barrel of a soldier’s rifle during a protest against the Vietnam war. This is transfigured into the flower slipped secretly beneath the softened, mock-camouflage in Minagawa’s textile. The uncovering of a secret detail beneath an unassuming fabric surface is an evolution of s/s 2008’s “Kakurenbo” (meaning ‘hide-and-seek’), which conceals white embroidered butterflies beneath large, dark navy circles. Although the technique requires the fastidious appliqué of countless fabric patches over the woven butterflies, the impression of the reveal is immediate and magical.

©MINA Co., Ltd.

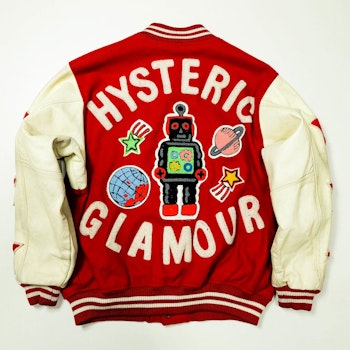

A little further into the room is a table dedicated to perhonen’s signature pattern ‘Tambourine’, a motif that has been continuously reinvented since its introduction in a/w 2000-01. For this textile, each ‘grain’ was hand-drawn and connected in an imperfect circle. According to Minagawa, the pattern suddenly appeared in his head one day, “as if it had come to the surface of the paper by itself”.

Becoming the company’s representative design, the pattern has been reused on everything from tiles, tableware, stationery, upholstery, shoes, curtains, jewelry, and stuffed animals. In its embroidered form, it takes 9 minutes and 37 seconds to complete a single circle.

Drawing closer to the sound of restless machinery flowing from the back of the room, the next section ’Ensemble’ is dedicated to the workers, equipment and facilities that come together in the manufacture of each minä perhonen textile. Lining the walls are rolls of pattern paper and enlarged drawings, shelves overflowing with stacks of dye-splattered buckets, spools of yellow-tinted thread, and the long, toothy reeds of industrial looms. On each wall are video screens playing wordless footage of the factories and workshops that the equipment was taken from. The layout of the display is candid and honest, as though everyone had just downed their tools and stepped out of the room.

Photo: Caleb Woodward

If the last two rooms were about the attention to detail involved in the creation of textiles, the next one illustrates the real scale of their production. Projected surfaces stretch deep into the long room as recreations of printing tables, with walls acting as long loom rows. Each panel is a moving video, a worker pulling ink across a screen as the looms whir ceaseless on the opposite wall.

Through dark corridors and up a set of stairs sits the second floor of the exhibition, the first section ‘Voices’ focussed squarely on the legacy and future of the brand. The walls are lined with interviews recounting years of collaboration with creatives across all fields, demonstrating the diversity of the brand’s ambitions. Especially interesting was the playground equipment designed with Tatsuro Tokumoto of JAUKETS, as well as collaborative work with influential Okinawan Ceramicist Jissei Omine.

The centrepiece of this area is a joint interview with Minagawa and Keiko Tanaka, who took over as CEO in 2021. The brand was founded with the idea of creating something that could ‘last 100 years’, with timelessness and responsibility at the core of its design concept. Minagawa hopes that by appointing a successor, the company can continue to adapt and create long after his retirement.

The last part, ‘Remix’, may have touched me the most. Long-time minä perhonen owners were invited to submit their pieces for repair and re-imagination. Each piece was adapted to the changes in the owners’ lives over the years since its purchase, presented alongside their memories and stories. I was moved by the extraordinary sense of full, vibrant lives being lived in these dresses: these were pieces of clothing that had seen weddings, funerals, childbirth, miscarriages, first dates, meetings, departures. Now they were being taken in, let out, shortened, lengthened, repaired and re-lined to suit the changing bodies, sensibilities and lives of the women who had loved them for so long.

I think this project might be the best demonstration of what really makes minä perhonen special— the respect for the fact that their clothing is the costume for the living of a life.

“TSUGU minä perhonen” runs until February 1st 2026 at Setagaya Art Museum.

Museum Hours: 10:00-18:00 (Closed Mondays)

Exhibition website: https://tsugu.exhibit.jp/