Tanned skin, towering lashes, bleached hair, and glittering miniskirts remain among the most polarizing images in Japanese fashion history. For many outside Japan and even within it, gyaru persists primarily as a caricature: loud, excessive, and unserious. Yet the spectacle of it continues to draw people in.

At its roots, gyaru was more than an aesthetic. It was a social system that pushed against Japan’s expectations of femininity and opened space for a style shaped by the feminine gaze. Once representing an estimated 10-billion-yen market, gyaru's influence was undeniable and held real cultural and economic power.

After the economic bubble in the ’80s, people suddenly had time and money to spend. Adults enjoyed nightlife where outfits grew flashier and more revealing, essentially irresistible to a youth culture seeking to look independent and mature.

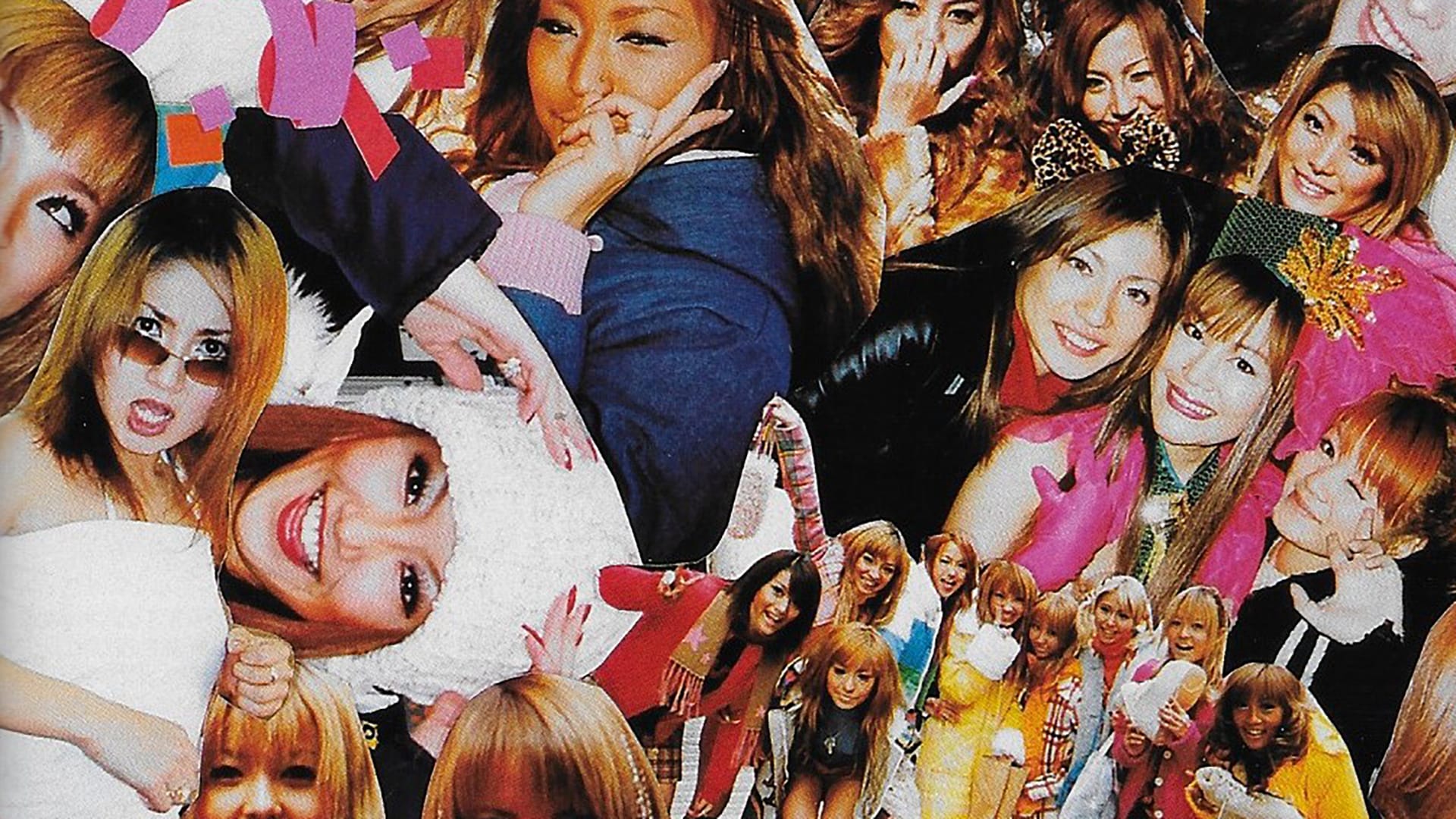

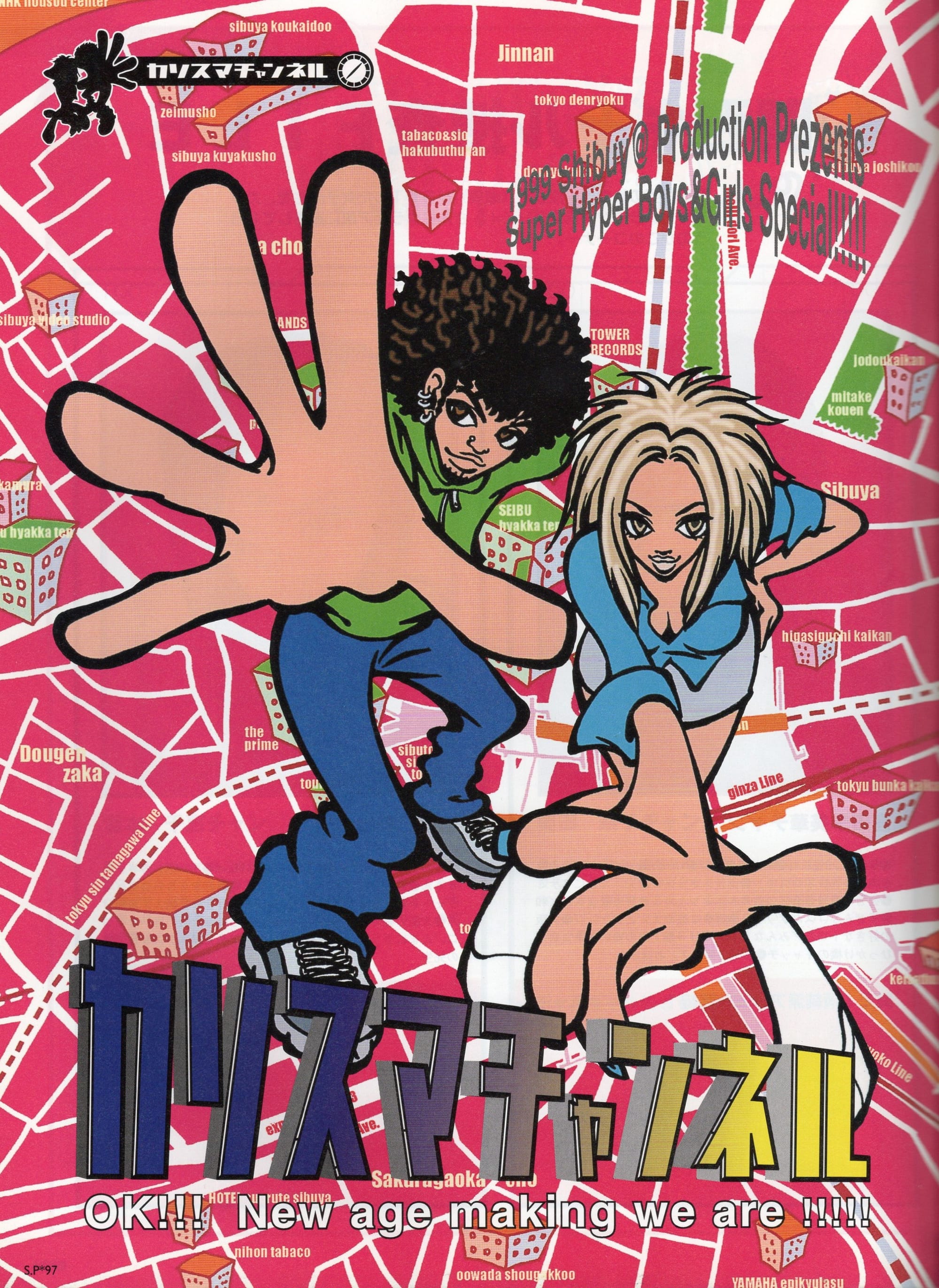

In the late 1990s, Shibuya was at the center of it all, functioning less like a neighborhood and more like a circuit. After school, girls could be spotted in clusters called “gyarusa” (gyaru circles), loitering around vending machines and fast-food counters. Makeup and hair were fixed in bathroom mirrors, following magazine tutorials. Street corners became regular meeting points where you were guaranteed to find community.

This was the environment that produced the Heisei-era gyaru.

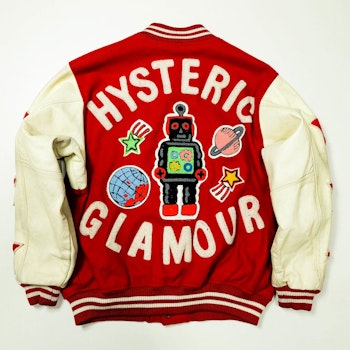

Flowing naturally from Shibuya Station, the triangular intersection of Shibuya 109 was designed to funnel a young crowd through its narrow corridors, a perfect trap for turning every passerby into an audience. But behind the polished storefronts, traces of postwar black-market activity lingered. These stores dealt in American secondhand clothing, and while they mainly featured menswear, they continued to sell shockingly well through the latter half of the 20th century. By the 1970s and ’80s, imported U.S. clothing had also begun infiltrating the area, inspired by surf films and a fascination with 1950s-era U.S. fashion. The open commercial space and steady foot traffic made it a perfect environment for experimenting with and copying new styles, setting the stage for the rise of the gyaru market.

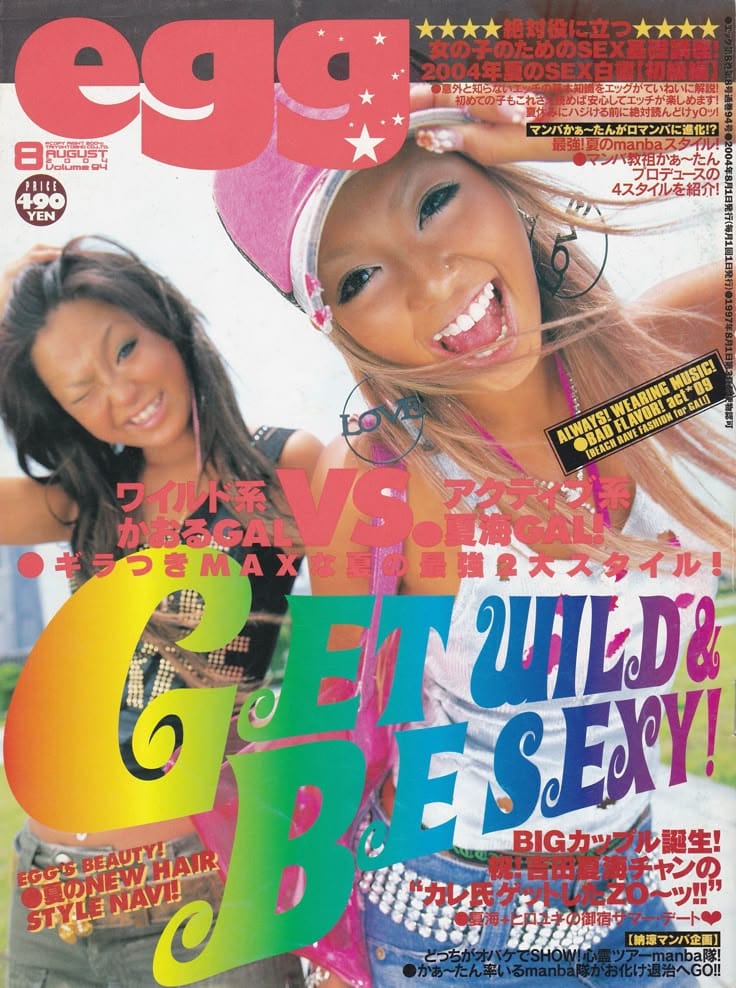

In the 1990s, Shibuya 109 became the perfect place for gyarusa to compete: who was there, how they looked, and how far they pushed tanning, hair, and makeup. There was always pressure to push it further. A bad look was noticed immediately, and a good one spread fast. More than just a mall, it was a live fashion index, and certain brands were essential in this era. Owning a highly coveted hibiscus coat from Alba Rosa or a d.i.a. belt signaled “real” gyaru status.

Gyaru was about exaggeration, but more than that, it was about standing out in a way that was chosen and deliberate. Girls dressed for each other and their crews, pushing silhouettes and makeup further not to shock but to stand out in a scene that rewarded commitment. Evolving from the kogal style in the early ’90s, being a gyaru meant being confident, hyper-visible, and having the attitude to match the look. You learned by watching, copying, and improvising on the go. For Heisei-era gyaru, this was crucial. Trends moved through magazines and people first, and idols like Namie Amuro gave everyone a visual reference, even spawning a carbon-copy style known as Amura.

Ganguro was the first true substyle of gyaru and came to describe a more extreme expression. These were the girls who took trips to the tanning salon to the next level, bleached their hair beyond white, and layered on makeup that made their presence unavoidable. The tans themselves were already charged with meaning. Since the early 80s, male surfers and naturally tanned beachgoers had populated Shibuya and dominated the “bronze ideal” in Tokyo’s youth imagination, and ganguro emerged as a playful, competitive challenge: “we can get even more tan without ever touching the ocean”. It was part performance, part rivalry, part assertion of style that demanded attention. Every detail provoked, from the bright, clashing colors to the deliberate lack of coordination intended to make a loud statement.

Being spotted in a good look at one of the main hotspots—Shibuya 109, Yokohama, or Harajuku—could mean being scouted and legitimized in the community. Titles like Egg and Popteen weren’t just magazines that documented gyaru; they were a reference point for the culture. Readers saw familiar faces month after month, tracked their favorite idols’ glow-ups, and followed shifting aesthetics across seasons. Features meant instant recognition, and disappearing from them meant something, too.

This was the system that Heisei-era gyaru developed: shaped by place, routine, and shared expectations.

Former gyaru often describe this period as intensely social. Days blurred, defined by outfits rather than dates. Many learned the gyaru way of life from older girls on the street. There was pressure from the complex social system, but you knew where you stood and what came next. The culture had an unspoken lifecycle, but aging out did not mean disappearing from it. There were typical transition paths, such as moving into hostess culture, becoming onee gyaru, or exploring subtler femininity. Even after a decade or more away from the scene, gyaru meetups and reunions still regularly bring the community back together, speaking to the dedication of the crews.

By the late 2000s, that containment began to loosen. Widespread commercialization and big-name idols like Ayumi Hamasaki brought the style into the mainstream. The explosive growth in the media fractured gyaru into sub-styles with increasingly narrow identities. Hime gyaru leaned into a rococo fantasy, Agejo embraced a nightlife glamour, and Ane gyaru emphasized a punk edge and maturity. New ideas kept getting mixed in, largely because blogs and early social platforms shifted attention away from location-specific trends. You no longer had to be there every day to be seen, and a good look could be noticed and copied anywhere.

As print magazines declined, so did the sense of a shared timeline. Individual branding replaced crew affiliation, and trends accelerated. Fashion became something you uploaded daily rather than negotiated in person. But gyaru only grew, shifting into a new era.

Reiwa-era gyaru aesthetics can be spotted far from Shibuya’s original scene. International communities reinterpret the style through a nostalgic lens, and with more experimentation removed from context, LGBTQ+ spaces lean into their exaggeration and campy theatricality. Youth culture raised on the internet draws selectively from the archive to curate the expression. Near Shibuya 109, studios provide “gyaru experiences," allowing anyone to try the look for a day and book photo sessions.

While there are no magazine editors watching or crews setting standards, social media steps in to document everything. The distribution is to a more fluid crowd, one that is temporary and constantly shifting, with a reach wider than ever.

Gyaru is unmistakably rooted in the Heisei era. It developed during a period defined by routine and shared references. Trends unfolded slowly, driven by familiar faces who proved their dedication to the scene. Nostalgia for this era is often expressed less in style than in rhythm, the repetition that made confidence feel earned rather than performed, and the friendships forged through that connection.

Reiwa works differently. Fashion continues to circulate without fixed scenes or timelines. Images move faster than gyarusa can form. The same aesthetics still appear, but as fragments lifted from context, recombined freely, and refocused on individual expression. The shift is subtle but decisive: for many, the style is a reference rather than a membership, and it can be identified by cues that can be assembled quickly. Most importantly, a new concept emerged: “gyaru mind.”

This idea suggests that being gyaru is about confidence, positivity, and resilience. If your mindset is gyaru, your appearance shouldn’t strictly define you.

This kind of afterlife is not unusual. When the original container disappears, style becomes portable, and the intention shifts. What was once a tight-knit community becomes more about personal expression. The change says less about gyaru than about how fashion travels once it spreads globally. What remains important in Reiwa’s gyaru is the power behind the aesthetic. Bold, assertive, and instantly readable qualities still carry weight in public spaces. Many find comfort in the idea that you do not have to explain yourself. The styling does it for you and represents a story of femininity that still needs telling, keeping the core spirit of gyaru alive and well.