With Evangelion 3.0+1.0 finally hitting Japanese theaters in just 5 days, I’ve once again been thinking a lot about the series and its movie-length conclusion, End of Evangelion. There's a lot that’s already been said about the meaning behind the series and the story of Shinji, and its ultimate message of strength to overcome trauma and end the cycle of self-destruction by learning to love yourself.

What are far less discussed, however, are the ways in which Gainax and Hideaki Anno used the medium of animation itself, tearing away at the animation process itself to give Evangelion the powerful thematic closure it deserved.

Spoiler Alert

If you haven't seen Evangelion... Wait. You haven't seen Evangelion?

What are you doing with your life? Go watch Evangelion. Here is a guide. Go.

The final two episodes of the Evangelion TV series, later complemented by End of Evangelion, were controversial when they initially aired. While I’m inclined to agree with Jacob’s analysis of these episodes as a powerful conclusion that embodies the ideas driving the series, although I would stop short of saying it's superior to what followed, the reaction at the time was harsh and led some to send death threats to Studio Gainax in response.

Thematically, both the end of the series and End of Evangelion explore how Shinji finds a way to love himself instead of relying on the validation of others for personal happiness. The various conflicting elements that come together to make up the story of Evangelion, including the Human Instrumentality Project that would merge all of humanity into one existence through the Third Impact, are extensions of this core concept.

Shinji is the key to this, and by continuing down his current path, he brings about the Third Impact and starts this Project into motion.

What’s the best way to conclude Evangelion while embodying what the series is supposed to represent? If the series truly wants us to consider the events of Evangelion beyond the end of episode 26 or the movie, it needs to reflect these ideas onto the viewer and jerk the audience out of their immersive viewing experience to challenge their own experiences in relation to Shinji. In short, it needs to turn Shinji into not just a vessel for the Human Instrumentality Project... it needs to turn Shinji into an audience surrogate through which we can experience these same struggles.

It won’t be surprising to anyone to note that Hideaki Anno’s own mental state heavily impacted the story and development of Evangelion. The series is a project as much about finding a way to understand his own trauma and depression as it is a series exploring these ideas. The Angels, the Evas... they’re cool, but they’re secondary, and can easily be discarded without losing the ideas of self-worth that define Evangelion at its core.

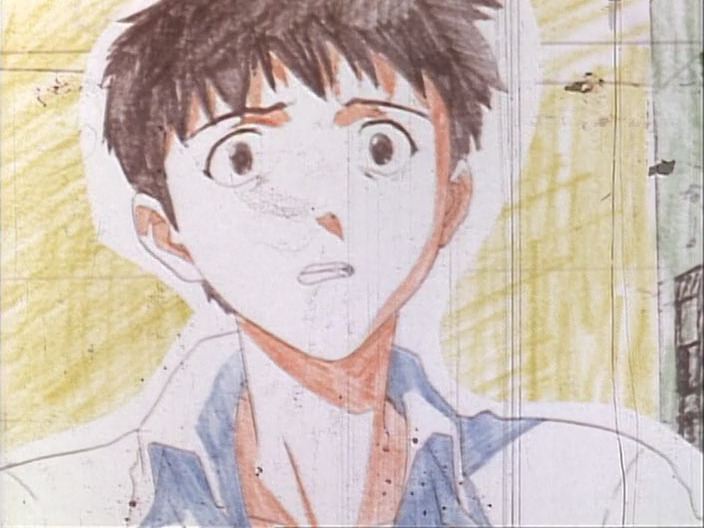

And the proof is in the final result. By the final few episodes of the TV series, budgetary and time constraints turned the series into more of a slideshow of images and storyboards and less into an animated series. Whether intended or a result of the issues with the anime’s production, the methods used by Gainax to put the show together despite these issues make it easier for the audience to implant themselves into Shinji’s state of mind.

One of the most powerful moments in the entire series comes with the death of Kaworu in episode 24, crushed at the hand of Shinji’s Eva. For over a minute, we as an audience are left to stare at the image of Shinji holding him in his hand before crushing him. This pause makes his death more meaningful as we think of how, for Shinji, Kaworu brought out his worst impulses while teaching him the way to move beyond them, and how this can relate to our own mental health struggles.

Shinji became obsessively attached to Kaworu because he felt everyone else had abandoned him... but Kaworu would listen. As he was falling apart mentally, it was Kaworu who was there to help him through, giving him an unhealthy, obsessive salvation from a mental breakdown that makes his death hard to take and the pause even more personally crushing. And yet, it was also Kaworu who challenged this very obsession in their every meeting, asking about his fear of intimacy which comes from Shinji’s own inability to love himself.

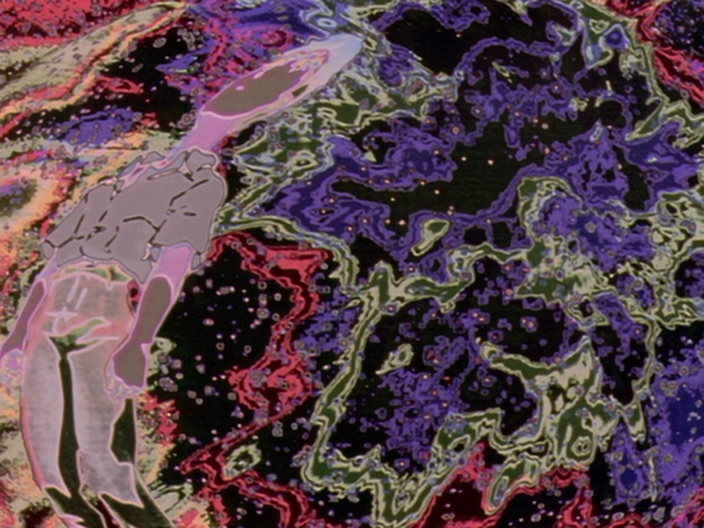

If we see Evangelion as a personal exploration of Anno’s own experiences with depression, this mental re-evaluation of Shinji’s coping mechanisms can’t and shouldn't be limited to the confines of animation and the anime itself. Much of episode 25 is devoid of interaction between characters, and the show visualizes Shinji’s crumbling mental state by corrupting the visual landscape of the series and countering his confusion with cold, silent text statements that only leave Shinji more lost than he was before.

Thanks to this, rather than introducing an omnipotent narrator or having these ideas challenged through conversation, we, the audience, take their place as a direct challenger to Shinji’s (and later, Rei and Asuka’s) self-destructive attitudes.

This is taken further in episode 26 when the other characters challenge Shinji’s self-centered view of the world that relies on others for validation while never trusting or loving them or himself. To him, the world is a corrupting and destructive force, and it’s for this reason the Human Instrumentality Project is further bringing their consciousness’ together.

By shutting out the animated world around Shinji, Evangelion instead replaces it with photography. These are mostly mundane photos, like a fence or a can on a seat, but they’re mundane signs of life that are jarring for the viewer by being so divorced from the context of the series. Combined with the removal of traditional animation itself for storyboards later on, like the classroom slice-of-life alternate reality, is a further rejection of the confines of animation and an example of Anno taking advantage of audience expectations by deconstructing animation itself.

By blending the tactile nature of hand-drawn sketches and photography, we allow ourselves not to confine these ideas to the anime itself and affix them to our own experiences.

The idea of using other mediums and distorting the creative format he uses to further his core ideas is something that has stuck through all of Hideaki Anno’s projects, whether in animation or live-action, and they persist into End of Evangelion. We see animation representing the Evas devoid of shape until its only colors, and we see the sketches of a child. Shots of 90s Tokyo are played over Rei and Shinji talking about these same topics, adding in the metatextual commentary that this becomes more important when facing opposition through this by interspersing it with footage of the death threats sent to Gainax in response to the original ending.

Evangelion speaks so heavily to myself and others, not just for its deft and personal handling of these topics in an unusual manner, particularly for anime, but by rejecting the limits of animation itself to further these ideas. Evangelion’s willingness to betray our expectations of how anime should look and act by placing us into the scene through on-screen text and deconstructing the animation itself are what allow the series to bridge the gap between fiction and reality and implant its ideas onto the real world.

The anime was a bold creative vision, not just because it was a powerful series blending personal introspection and science fiction, but because it knew exactly when not to be an anime at all.

This piece was originally published to OTAQUEST on March 3, 2021