On Sunday, October 13th, the all-female Japanese theater troupe known as the Takarazuka Revue ended a recent 3-month sold-out engagement of their seminal adaptation of Ryoko Ikeda’s Rose of Versailles at the group’s major theaters in Hyogo and Tokyo. This special performance marked the 50th anniversary of the troupe’s initial performance of their original musical based on a manga whose dual identities have since become intrinsically linked to one another. With each iteration on the show comes new interpretations on the source material, each telling the same overall story of the final days of the French royalty and the French Revolution but from different perspectives of major characters in this world.

Rose of Versailles is a series both timeless and flexible enough to be constantly reinterpreted for new audiences. Whether this be in its original manga form viewed by new audiences across generations, new stage adaptations both in Japan by the Takarazuka Revue or a recently-premiered Korean musical, or the upcoming new anime movie adaptation from Studio MAPPA, the story is proof that truly classic stories never lose relevance.

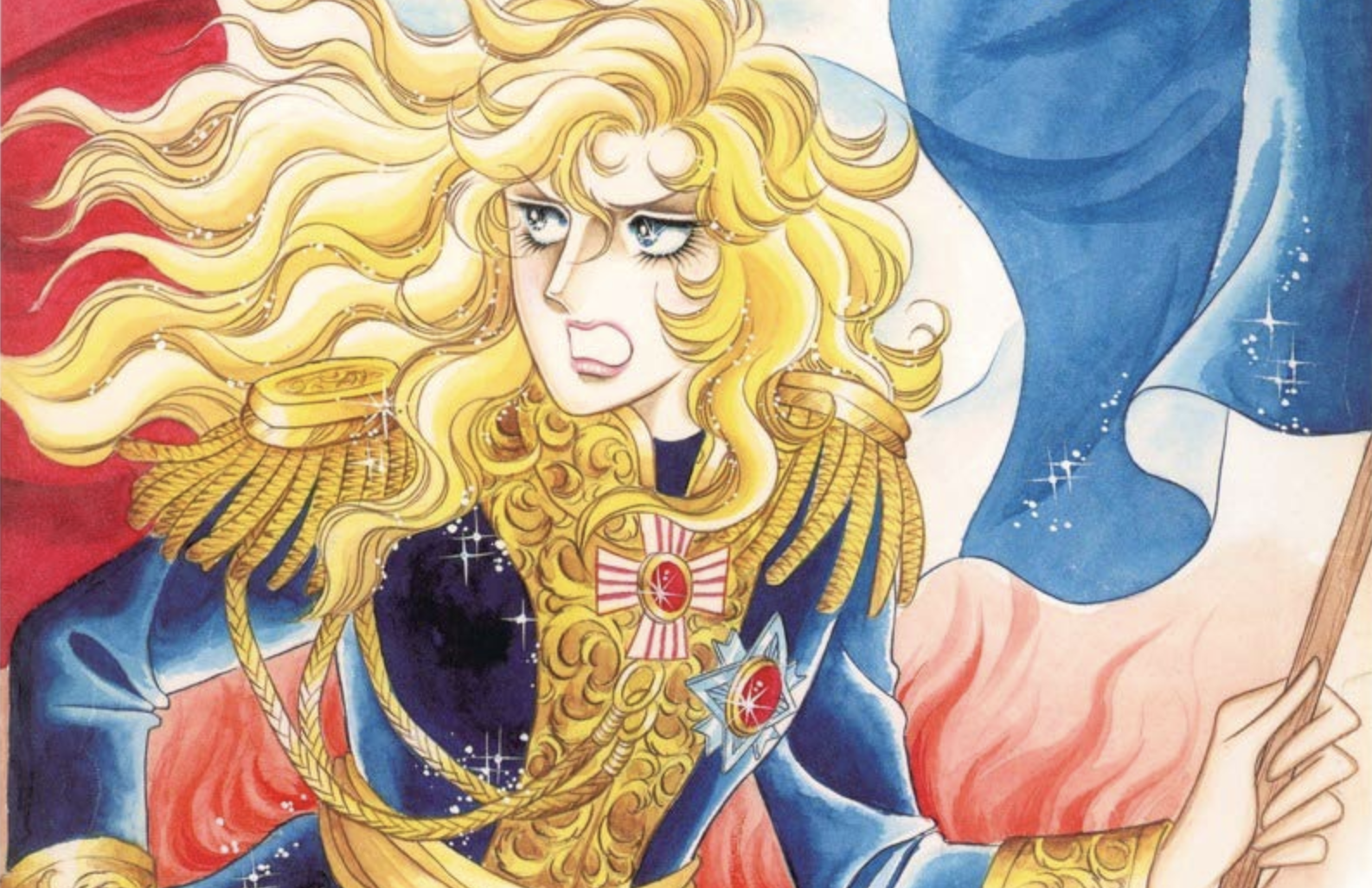

The original manga is generally regarded as a touchstone of the shojo genre even today, with modern series, artist collectives like CLAMP and more taking inspiration as its lineage stretches throughout the modern landscape of Japanese manga. It’s a story of two women amidst the French Revolution: the wealthy queen Marie Antoinette divorced from the suffering of her people engaging in a secret relationship with Swedish nobleman Hans Axel von Fersen, and Oscar François de Jarjayes, a female officer in the all-male Royal Guard whose ambiguous appearance and unusual role make her both a standout figure within the army and someone acutely aware of injustices within government and society. As her own love for a common man in Andre grows, once the revolution begins, she fights in earnest for the revolutionaries.

The story is not only a well-researched portrayal of the events surrounding the Revolution beyond the fictionalized accounts of Oscar and Andre, but wrote in part as a reflection by Ikeda on the violence and infighting in the Japanese New Left and its impact on feminist movement’s attempts to construct a new female image between idiologies of consumerism and socialism that mirror the events of 17th century France. Through its centering of female voices within this revolutionary conflict and the dual love stories at the heart of this story, the series defied the typical infantilization of stories aimed at women.

More importantly, Ikeda empowered her female characters as defining voices of a revolution, contrasting the typical names associated with the era and representative of the many unspoken voices of history and making a case for women to define these roles now and in the future and make themselves heard. Oscar, as a Royal Guard officer, is quite literally a woman in a ‘man’s world’, acutely aware of society beyond the palace and its injustices. They're a particularly pointed character, especially today in a world with growing inequality and a Japanese government still lacking in female representation in leading office.

Unsurprisingly, gender and power are running themes of this story, from its core tension and political turmoil to the dramatic romantic exploits of its protagonists. It complicates and humanizes even characters associated with villainy in the tapestry of this revolution like Marie Antoinette. Her love with Ferzen is one that strikes division within the court, causing scandals both of her own doing and fictionalized as weapons against her by her enemies. But her love is genuine, and the tragic circumstances keeping them apart before being sent to the guillotine as someone with genuine regret, paint her as a ruler that certainly was wrong in her time, yet whose death is no less tragic.

This is a political series, but one that understands romance itself as an inherently political act. It’s through romance that the seeds of revolution are explored, just as humans have connected and shared ideas through forming connections that resonate and inspire.

No wonder the series, serialized in Margaret magazine in 1972, was a near-immediate hit with young girls at the time. The first Takarazuka adaptation begun in 1974, and for a series so politically-astute and centered on the unspoken female voices perhaps no group could be better for telling the story than one where even the female roles of the story are occupied by women whose voices are often overlooked in real-world histories.

At a time when audiences for the long-running theater troupe were declining and the group were at risk of bankrupcy, the show transformed their fortunes and led to a boom for both the manga and theater troupe alike, with the latter continuing on a strong footing for much of the decades which followed. Since then new stories have told these strokes but highlighted different voices to bring new perspectives to the events of this world, and the series is so intrinsic to the identity of the Takarazuka Revue today that a statue exists on the grounds just outside its Hyogo theater.

Each new perspective brings new layers to the performance. Shows the troupe have performed placing Oscar and Andre have contrasted royal life to the common folk, while shows with Marie Antoinette or Ferzen as the central character have tended to focus further on the royal courts and the ambivelence fueling revolution. This extended to the most recent show, a Ferzen-centered production that served double-duty as the first Japanese performance of the show in almost a decade, as well as the final performance of the Yukigumi troupe within the Takrazuka Revue’s top star, Ayakaze Sakina.

In proof to just how flexible this series is to bring out new meanings from its ever-evolving text, a new song titled C’est la vie, adieu was performed that represented the final goodbye between Ferzen and Antoinette, alongside this era of French history for the uncertainty of whatever comes next. Love in the form of goodbye and a wish for a bright future, it serves double duty as the goobye for the lead actress, a Top Star leaving the group after a near-20 year run to perform beyond Takarazuka in future.

Which brings us, at last, to MAPPA’s anime. The 1979 anime TV series adaptation was as revolutionary in animated form as the manga was years earlier, and remains a visual identifier for the genre today. While it may at first seem a near-impossible task to take a still-beloved anime and remake it, especially when the request requires the team to cram 40 episodes of an anime into just a single 2 hour film.

History suggests we should not fear. While it is almost certain that this film will not have time to cover the full extent of the manga in this time, these intimate details are not the reason audiences continue to cite Rose of Versailles as one of the most influential anime and manga series of the past 55 years. Its empowering characters and enduring romance, its constant flexibility for new adaptations in theater, anime and other mediums, set precedent that as long as those developing the series recognize these core tenets for The Rose of Versailles’ enduring appeal. This is a story modern anime audiences deserve now more than ever.

Recent years have seen an indulgence of remakes across the anime industry. In many cases, either through a lack of creative vision or a story that no longer resonates with modern audiences, these have often felt like unnecessary indulgences that dilute the impact and legacy of their original source material. Yet there’s an edge to Rose of Versailles that remains pertinent even today, and early trailers suggest the MAPPA team not only know how to condense these stories but truly refresh these stories for modern audiences. Time will tell, of course, but the recent sold-out run of Takarazuka Revue performances even 50 years later are a showcase of the cross-generational resonance of this iconic piece of shojo history.

Maybe if the anime proves to be a success, we’ll be talking about this series 50 years from now, as well.