Open up a copy of any Shintaro Kago manga and you will immediately see sights of either piss, poop, or entrails. For that matter, it might even be a combination of all three: such is the reason why the author’s name has developed such a notorious reputation over the past couple of years.

This article contains NSFW imagery and discussion of topics that some readers may find disturbing.

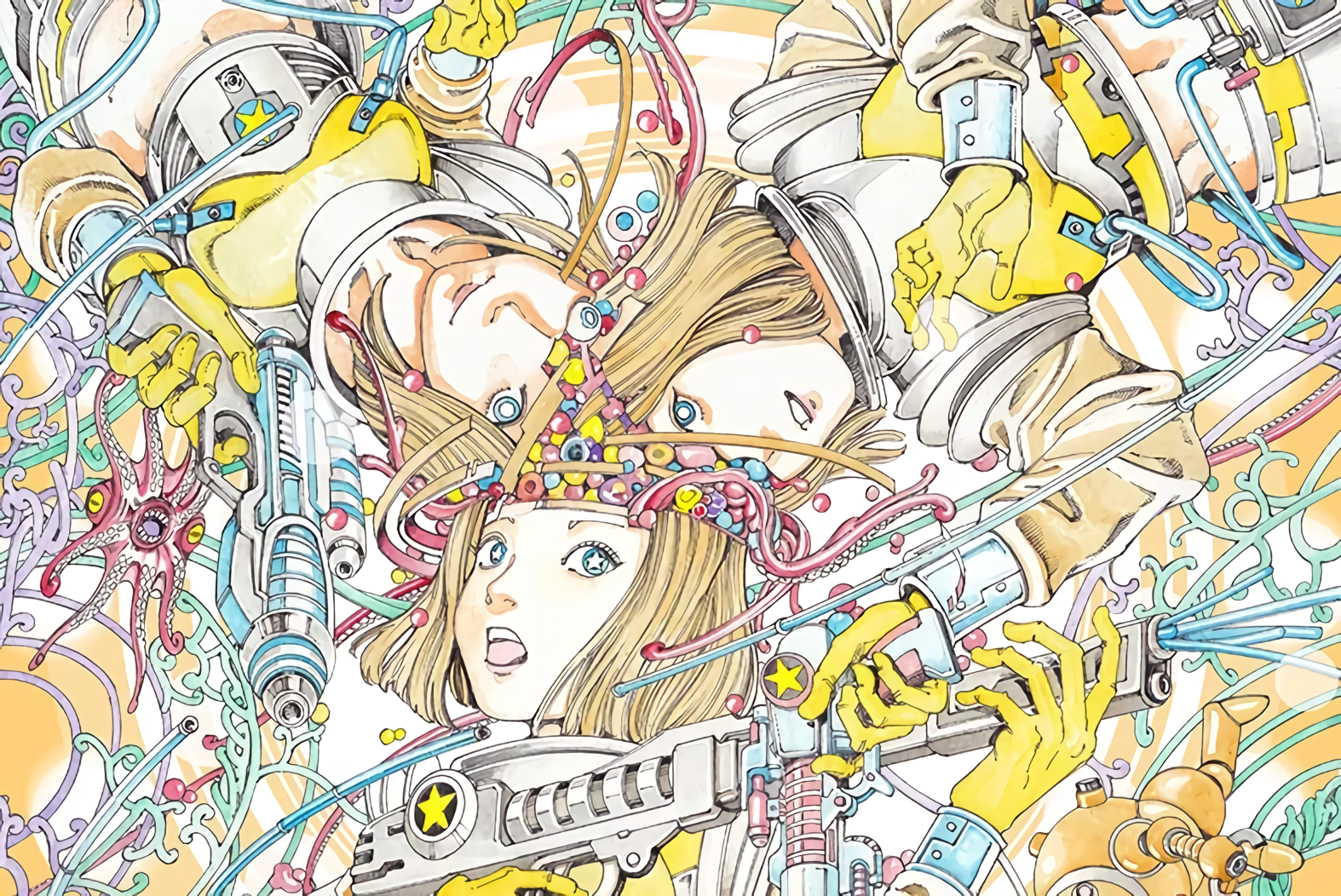

Many fans outside of Japan first came into contact with Shintaro Kago’s unique brand of ero guro artistry thanks to his illustration work on Flying Lotus’ 2014 album, ‘You’re Dead!’. He provided both the front cover and several drawings for the inner record sleeves, but it took until 2018 for one brave English publisher to step forward and actually license one of his works: Dementia 21, available via Fantagraphics.

Since then, Princess of the Neverending Castle got picked up by Hollow Press and DENPA took a chance on Super-Dimensional Love Gun, a collection of short stories. It’s therefore easier than ever to peer into the mind of Shintaro Kago, but we are arguably no closer to answering the question of why he creates the depraved things that he creates.

Examining his inspirations provides possibly the only course of action.

Shintaro Kago and Surrealism

In an interview with Asian Movie Pulse in 2021, Shintaro Kago named his most important influences as ‘Katsuhiro Otomo, Fujiko F. Fujio, Eric Idle, Yasutaka Tsutsui.’ Some of these names are arguably at odds with each other in terms of subject matter, but a varied and contradictory set of influences is precisely what makes Kago’s artistry so unique.

To take Eric Idle and Yasutaka Tsutsui first, both of these creators can be placed broadly in the camp of surrealism. The former was a member of the boundary-pushing comedy troupe Monty Python, while Tsutsui combined elements of surrealism and psychoanalysis with science fiction to create such seminal works as The Girl Who Leapt Through Time and Paprika. Their influence is plain to see throughout Shintaro Kago’s large body of work.

As a member of Monty Python, Idle was apparently responsible for much of the group’s more raunchy material, which fits in well with Kago’s generally NSFW approach. Many of his works also deal with science fiction and psychological themes in the same way as Tsutsui: the idea of different levels of reality that Paprika evokes, for example, can be found readily in the kaiju murder mystery Anamorphosis no Meijuu, which plays around with miniatures and forced perspective.

You could also point to the kind of absurd animations that Terry Gilliam produced for Monty Python’s Flying Circus as an influence on Kago’s mind-bending art style, but Salvador Dali undoubtedly has a bigger part to play in this. The author explained in the afterword to Dementia 21 that receiving a Dali art book was what caused him to fall in love with ‘Surrealist things’ as a child, providing a concrete connection to perhaps the most famous figure of the movement.

Furthermore, Shintaro Kago doesn’t shy away from surrealism’s more political connotations. While he maintains that everything is ultimately up to the reader’s own interpretation, his disdain for Japanese imperialism is clear in such early works as Kagayake! Daitoua Kyoueiken.

Practically the same central concept of giant, naked women is also used in The Ultra Power Mongol Invasion (Choudouryoku Mouko Daishuurai) to explore the evils of capitalism and colonialism in equal measure.

A Question of Scat

If one thing sets Shintaro Kago apart from most traditional surrealists, however, it is his frequent depictions of shit and scat fetishism.

Neither Idle nor Tsutsui nor Dali were afraid to push the boundaries, of course, but they didn’t obsess over human excrement in quite the same way. In this sense, Kago is actually more like George Bataille, who clashed with André Breton during the heyday of surrealism over what kind of topics the fledgling movement should cover. Certain parts of Story of the Eye (L'histoire de l'œil) definitely bring to mind Kago’s more depraved approach.

As it turns out, Kago didn’t exactly want to become a scat mangaka. He explained in a 2008 interview with VICE that ‘I chose the theme because at the time that I started doing it, nobody else was famous for it in the manga world.’ A lot of his early works were published in adult magazines where such fetishes were popular, so it could be seen as simply a matter of circumstance.

On the one hand, it’s definitely true that as you make your way through Kago’s oeuvre to the modern day, the amount of shit-themed content decreases. Vignettes as stomach-turning as the one in Kagayake! Daitoua Kyoueiken where the main character is forced to curl out turds for customers at a bank that deals exclusively in poop don’t really crop up again, although the amount of blood and gore remains the same. That’s probably a good thing, to be honest.

Even so, Kago’s association with poop is kept alive by virtue of his annual ‘Unco Film Festival’ (Shit Film Festival). Since 2010, it has awarded short films and animation that deal with human excrement in some shape or form: the next edition of which was recently announced to be happening in May of next year.

Shintaro Kago in the Modern Manga World

The thing is, Kago maintains that he’s not actually into scat. This obviously then begs the question of why he keeps associating himself with it, but answering this requires examining the rest of his influences first.

By now, it should be obvious why Shintaro Kago would name the likes of Katsuhiro Otomo and Fujiko F. Fujio. Both creators deal with science fiction and alternative visions of the future, fitting right alongside Yasutaka Tsutsui in terms of their genre trappings as a result. Even if the tone of Doraemon is obviously a whole lot more irreverent than Akira, this might have informed his humorific approach. One can’t also help but imagine that Tetsuo’s transformation loomed large in Kago’s childhood imagination.

Another interesting name comes up in the afterword to Dementia 21: Shigeru Mizuki. More specifically, Kago says that receiving one of his picture books about Japanese yokai as a child was what inspired him to start drawing more ‘dense/precise’ art, the effects of which are plain to see. It might sound strange for someone as depraved as Kago to draw inspiration from the man who created the very kid-friendly GeGeGe no Kitaro, but Mizuki never shied away from the grotesque in his character designs, scarring lots of kids for life as a result.

Moreover, Shigeru Mizuki was also heavily influenced by the gekiga movement. He actually saw GeGeGe no Kitaro as one way to introduce its ideals of strong narratives and dark visuals into the mainstream, even pivoting towards more somber explorations of Japanese history in later life. You can’t put him in a box, and the legacy of gekiga is much more present in Kago’s works than perhaps some of his contemporaries.

As an artist, Kago is not infrequently compared to the likes of Junji Ito. Certainly, there are comparisons to be made in terms of their graphic art and goretastic approach, but Kago’s works often go one step further and challenge the medium itself. Uzumaki might read like a horror movie, but Fraction is like getting halfway through said horror movie only to realize that the murders on screen actually happened.

The snuff might put you off your popcorn.

The Boundary-Breaking Project

To my mind, this is the influence of surrealism colliding with the desire for strong narratives as informed by gekiga. Not only does this prove that every single one of the inspirations explored so far are essential to understanding the kind of artist Shintaro Kago is today, it also explains a little bit of why he feels compelled to create the depraved things that he creates. Even so, there is something deeper lurking beneath the surface.

It’s already been established that some of Kago’s most shocking, shit-themed stories were partially produced as a matter of circumstance. They may decrease in number over the course of his career, but they also can’t simply be sidelined for the sake of convenience. Like it or not, they exist.

With this in mind, everything that Kago has ever created should be understood as one part of a wider boundary-breaking project. He admitted to Neocha last year that ‘There’s no taboo that I wouldn’t work with,’ actually finding pleasure in getting a reaction. Our aversion to our own discharge could be why he put it front and center in the early portion of his career.

Be it compulsion or simply sick fascination, Shintaro Kago is one artist who always stays true to himself. His creations certainly aren’t safe for work, but they do cause you to question where you draw the line and why.

There might be something of value at the end of that thought process.

You can see more Shintaro Kago's art via his Instagram.