The methods we use to record the present and the past are ever-evolving. More than that, this ever-changing status quo brings about new questions. What can we record, and what can never be captured, inevitably warping our perceptions of time and event from the so-called ‘true’ experience of the moment? Then there’s the medium, and the language, and the message. Tokyo itself is a tapestry of experiences superimposed upon one another, built and rebuilt, to create a towering home, to such an extent that all of its deluge of museums from major institutions to a single room in a hidden apartment building are attempts to scratch even the surface layer from this impenetrable abyss.

The Yebisu International Festival for Art & Alternative Visions, originated in 2009 and this year helping to celebrate the 30th anniversary of the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum it uses as its main location, makes its vision for 2025 an attempt to understand this impossible question. Under the theme of Docs: Images and Records, using the famous museum as a base but spreading far beyond to venues across the city, seeks to understand the layers and history both internal and external that shape the self, the city and the world. Running until February 15, 2025 there’s plenty to uncover, and more to understand.

Exiting Ebisu Station and taking the walk towards Ebisu Garden Place, the location of the main museum housing for this festival, bold advertising stood proudly above the walkway promoting an event whose suburban Tokyo home feels just as contradictory as the questions the show wishes to elicit from its visitors. Regal 19th-century style European hotels repurposed as flashy wedding receptions give an impression of grandeur via the influence of Western aesthetics as a shorthand for high market, all stood mere streets away from slivers of winding, olden, traditional buildings. Japanese conveniences are warped to a blend of East and West in this serene, strange place.

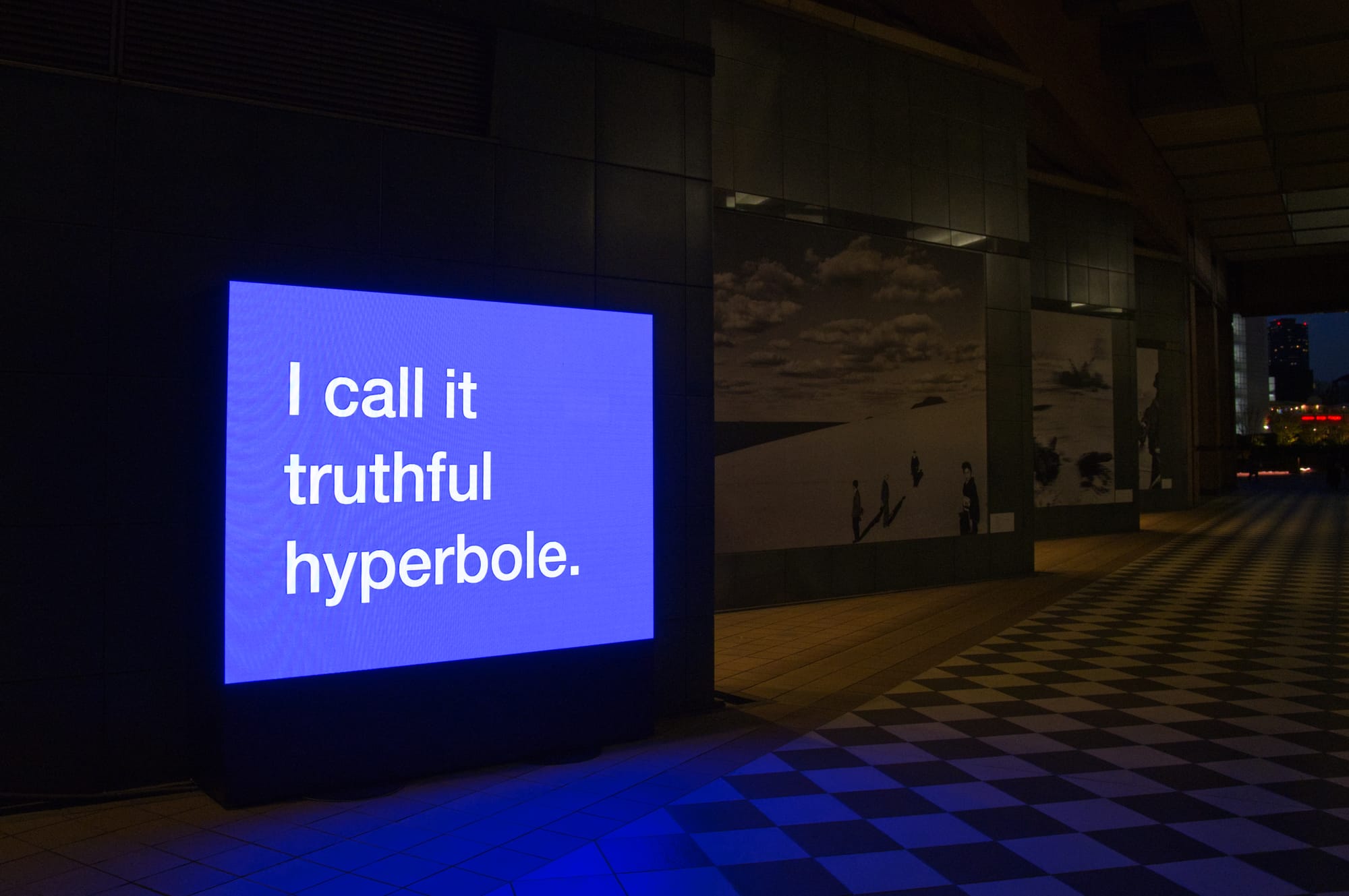

Contradiction is even the first impression attendees of the festival will likely experience, also. Approaching the Photographic Art Museum, the shaded corridor leading towards the entrance of the institution was illuminated only by gaudy blue lights and club music. Dotted outside and throughout the venue were these glowing works of Tony Cokes, one of the feature artists whose work here used this blinding light as a megaphone and commentary on current affairs within a social and racial context. This particular art stood alongside the museums more permanent photos of war and embrace, blasting quotes from Donald Trump accompanied with questions surrounded the power of language.

It’s hard not to consider this location a deliberate choice.

In its mission statement for this year’s theme, the event hopes to consider our changing relationship to photo and the moving image as its tools become more accessible, and how the document of fact and the documentary as an expression of fact can create an ambiguity in the truth to such an object. What is the role of the image in shaping reality, and what can it really show when its manipulated within a space, within our minds, and within our own personal worlds? How has that changed?

Cotes asks these very questions in his work. While the power of written word is slow in a modern context such that the argument of truth rages to the point of irrelevance before the matter can be adjudicated, a record of history like this makes it unavoidable until we confront it.

It’s this considered, deliberate reflection of modern life that runs throughout the event, even if other showcases are not quite as in-your-face as this one. This is reflected more subtly in two standout newly-commissioned pieces: Oda Kaori’s Recording with Mother “Working Hands”, and the community-driven “Spring, On the Shores of Aga”, by Komori Haruka.

While these veer more into the realm of traditional documentary than experimenting too much with the form as other works, each take advantage of the space and setting to provide greater clarity on why these topics matter in viewing images beyond the national and historical into the personal. With "Working Hands", for example, Kaori returns to the subject of her mother, lingering on the mundanity of taking the train in her hometown of Takashima or crafting small wooden dolls as she shares the unspoken side of her life that brings manifest to her routines. Talk of school, of adapting to changing circumstances, hidden behind cuts on hands and exhausted faces we linger upon.

On the other side, Haruka’s work documents the community struggles that continue once the cameras have gone away. In some ways a continuation of the work of Living On the River Agano by director Makoto Sato from 1992, the work sees Haruka visiting the town impacting by the chemical spills and mercury poisoning caused by company’s based on the river that led to a spike in those suffering from Minamata Disease living on the banks.

Rather than once again litigating the incident and in the spirit of the original’s focus on the lives of those trying to support each other in the background of injustice, the film focuses on its memory and the passing down of this through education, stories, new screenings of the film, and journeys through a landscape and people irrevocably changed. Ordinary houses are re-contextualized as the homes of those who lost their lives without being recognized, all while some consequences remain untouched.

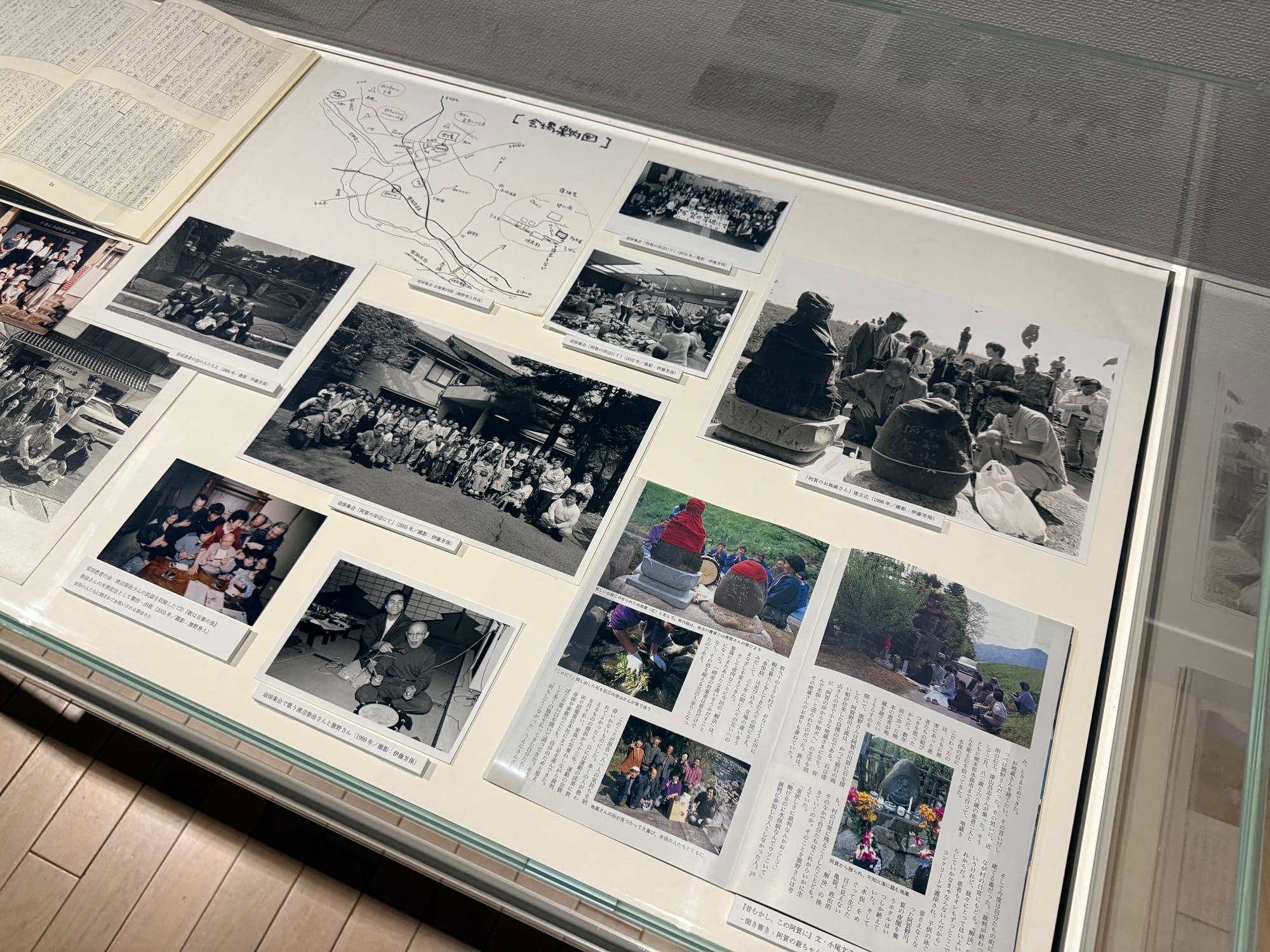

Surrounding the limited seating are books and handwritten journals and photos that remind us of what was lost. Many come from after the 1992 film and show that just because the media went away, doesn’t mean the suffering ended or the fight was over. And this can pass it on for more people to remember and continue that struggle.

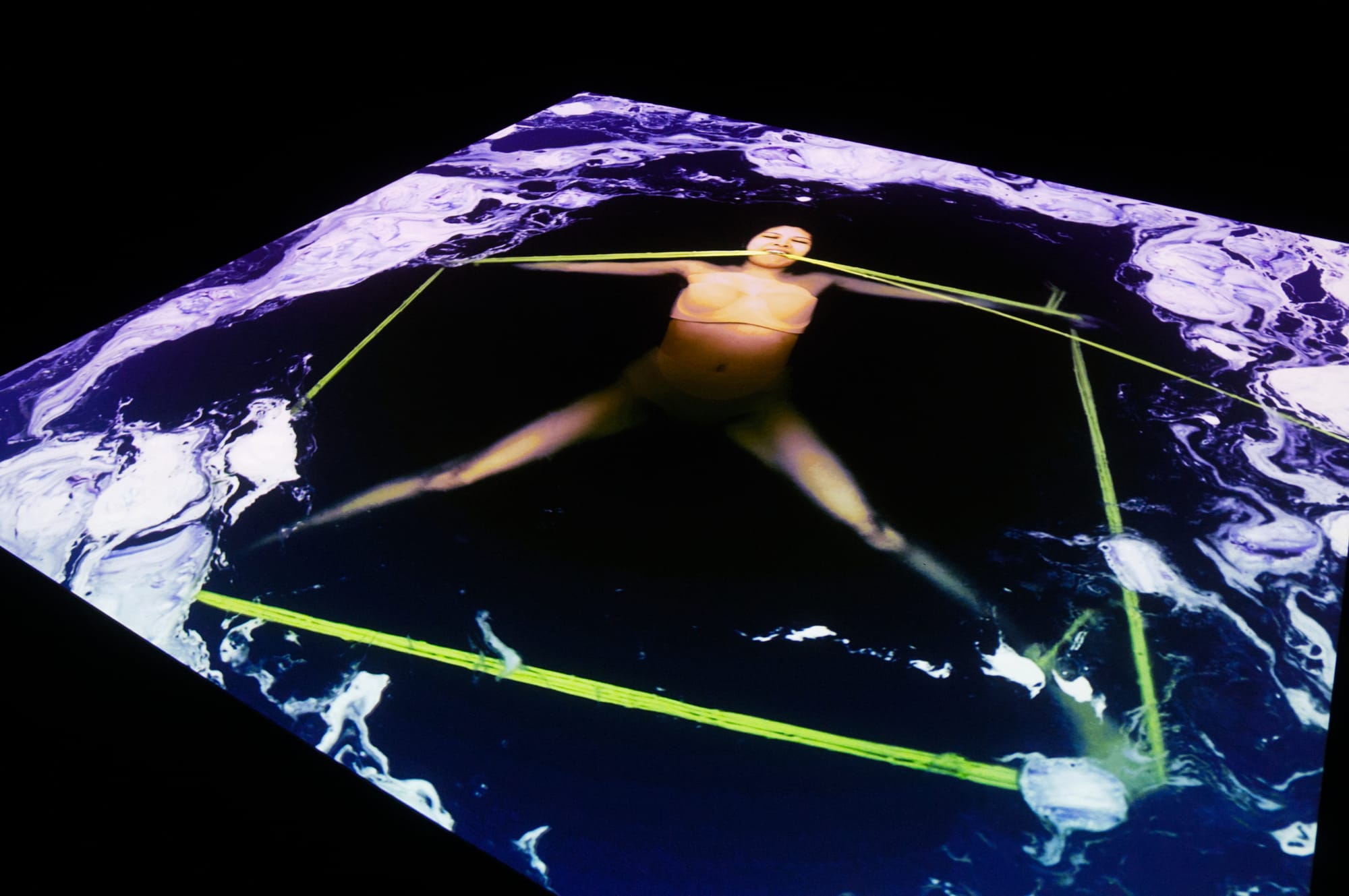

A concurrent theme throughout the space was how our sense of place warps how we view and remember events, as well as the human experience. The exploitation of labor was brought into stark focus by Kawita Vatanajyankur’s "A Symphony Dyed Blue", which features the artist naked in a pool of blue dye tied and tossed around without pattern or reason. "Landscapes" cuts and blends dozens of images into a continuous stream and projects it to the wall for us to merge our differed understandings of the world and the variety of nature across the planet into a single united frame.

The narrative continues once you step into the streets of Ebisu, away from the main Photography Museum. Here the streets themselves, windy and narrow but filled with small businesses and alleyways both run down and hidden from the world, tell their own stories of the way in which life sprung without order in any pocket it could find and allowed it to thrive.

Down one path, a run-down apartment building seemingly disused and covered in vines stands next to an open-plan glass building that appears almost-new. This building houses MEM, a single-room gallery that screened "Diary of Eve’s Land" from Kyoko Kasuya. The point of this exhibit is a comparative exercise, the artist having taken a trip to Saudi Arabia in November and December 2023 to speak to women about the differing desires, expectations, and changing lives for women living in the region.

Time, history and sociology reach out as core themes, contrasted by the walls depicting photos of everyday life and the mundanity ignored in the production process that uses simple message chat log screenshots to force us to avoid boxing our subjects into the narrow window of ‘a voice of a generation’. Yes, we’re discussing how life is for women in the area, but they’re more than a representative voice, and this emphasizes that.

It contrasts heavily to "The Commercial Hotel", which centers the depravity of the private lives hidden in the commercial space by featuring molded plastic feces and used underwear as the masked artist mimics masturbation and lies in grotesque piles of masks to bombard the witness to inner impulses made manifest.

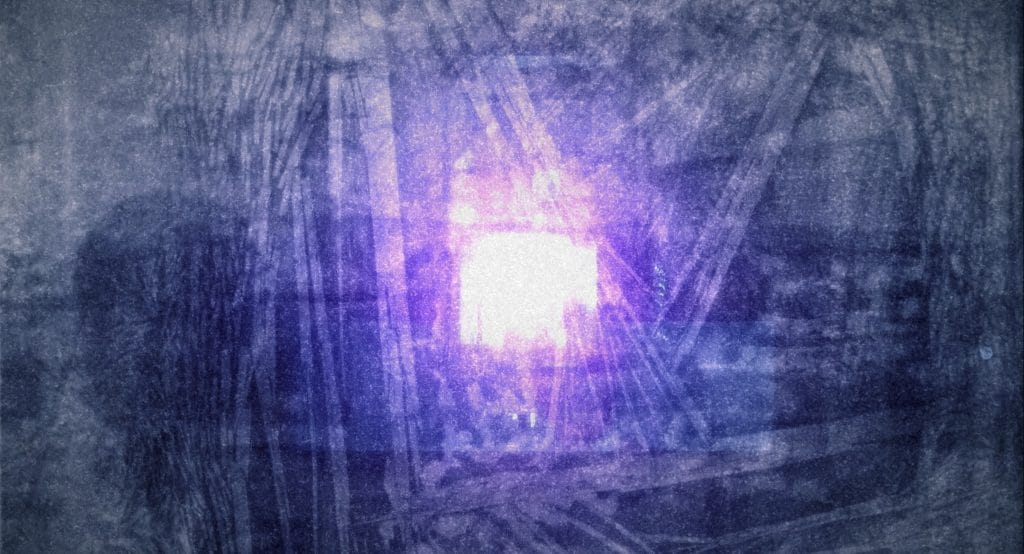

For the impressive work on display in the Photographic Music, once you step beyond into the wider Ebisu area the true depth of the festival unveils itself. In experiencing these exhibits, visiting spaces like the Poetic Space to see Toyama Yuki’s "Scenes of Absense", featuring photos taken by the artist while caring for their dying mother which deliberately avoid photographing her mother, or KOMA Gallery, we’re forced through tiny alleyways and up narrow staircases into unconventional art spaces. We embed ourselves into suburban life, into a home.

As we wander, we create our own images and records. I take note of a man riding his bicycle in a clearing at the end of the road by the train tracks. Awkward maneuvering in narrow stairwells. Mundane moments that, again, bring depth and layers to the mundanity of life but are nonetheless important in shaping our worldview and impressions of the space around us.

Beyond the exhibits, screenings emphasize this exact conclusion. In some screenings we step back to observe history, particularly the student protest movements that pitted a new postwar generation against the older generations during the 1960s and 1970s as major treaties on nuclear proliferation and defense were signed between the US and Japan. Amidst protest was flourishing artistry, with students capturing this turning point in Japanese history via new documentary and avant-garde styles that sought to radically shift the consensus of Japanese society.

All this and more can be seen at the Yebisu International Festival for Art and Alternative Visions running until February 16th, with many of the artists holding talks or workshops across the event. Finding new stories hidden in the corners and side streets often overlooked in the secluded side streets mere minutes away from the bustle of Shibuya, it's an enlightening exhibit worth seeking out.