The Mobile Suit Gundam franchise's rags-to-riches origin as a series that went from obscurity to the biggest anime franchise in the world is almost mythical at this point. The original Mobile Suit Gundam series was destined for obscurity, having been canceled early by the production committee and reducing a 50-episode run to 43 episodes, before Gunpla toys revived interest in the franchise and paved the way for future entries that shot the series to mainstream success.

This somewhat over-simplistic portrayal of events underplays how Gundam, thanks to Gunpla and the Anime New Century Declaration, changed the shape of anime and anime fandom forever.

How Gundam Ended and the Origins of Gunpla

To unpack the myth of Gundam’s origins and portray just how much more influential Gundam was on the world of anime than most assume, we need to explore what the franchise was like before Gunpla burst onto the scene. After all, Gunpla weren’t the first toys to be produced within the Gundam franchise.

The 1970s TV anime landscape was dominated by robot anime that were easy to capitalize on with toy lines. At the time, alloy toys were the name of the game, and many of the ‘super robot’ anime of the decade, from manga adaptations like Mazinger Z to shows like Gaiking, were sustained by alloy toy sales. These series featured less realistic, humanoid robots that were easy and cheap to replicate and produce in stiff alloy molds, while being capable of flashy moves simply not possible by real robots.

Sunrise had partnered with Clover on anime like Invincible Superman Zambot 3 to moderate success, which led them to once again partner up on the Mobile Suit Gundam franchise. This series also marked a departure from ‘super robots’ to ‘real robots’, with the Gundam being designed to be more mechanical and weapon-like as opposed to the human-like machines of predecessors.

And yet, the toys produced by Clover were opposed to this and more in line with prior super robots, with rocket punching arms, mismatched colors, and none of the precise movements the real machines offered.

As the stories tell, the Gundam anime was cut short as a result of Clover cutting support and pulling out due to low toy sales, with the diecast toys mostly wound down, only making a brief re-appearance around the release of the compilation movies.

The compilation movies acted as a re-edit and re-interpretation of the original series. They removed some of the lingering super robot elements of the series that found a place in the show both because of the legacy of the genre and because of pressure from the likes of Clover to introduce more toy-like elements to save the fledging toy-line. These movies were not only some of the highest-grossing movies of 1981 and 1982, but their success paved the way for future entries in the franchise and the monolith we know and love today.

This is where Gunpla comes in. With the series over, Bandai secured the rights to produce a line of model kits based on the Gundam series, and released the first kit based on the RX-78 in 1980 for 300 yen. More kits followed, and unlike the derided, childish Clover toys, these were beloved by the franchise's older audience. Not too complex to build, far more realistic to the series and, importantly, cheap, they were ready-made for the audience the series had grown an unexpected fanbase with.

Even then, this early line of Gunpla is different from what we see today. The Grading system that rated build complexity and facilitated the release of large-scale, highly complex builds was yet to be introduced, and only a small selection of kits were made available in the first year. Still, it captured the imagination of the show’s dedicated fans and had strong sales.

Gunpla captured the imagination of the slightly older demographic of the franchise that could support and sustain it through fun, cheap, and easy-to-build model kits. This alone had a major influence on the medium of anime, as further real robot anime that favored function over humanoid designs were produced alongside lines of model kits.

But Gunpla is only half the story of Gundam’s impact on the world of anime... the second half is typically relegated to a footnote in the English-language lexicon of understanding Gundam’s phenomenal rise to success. Gunpla laid the seeds for Gundam’s revival by exciting and mobilizing a nationwide audience of university students and adults, but the events that occurred when these fans came together in their love of the franchise changed the perception of anime forever.

The Anime New Century Declaration

The Anime New Century Declaration made the non-anime fan take notice of the growing audience for anime in Japan and changed the child-only perception that had built up around the medium before this point. It wouldn’t be unfair to suggest that this event changed anime forever.

While the original Mobile Suit Gundam was unpopular with its target audience of children thanks to its mature ruminations and critique of war (and a hero who would have preferred to be anywhere but the middle of an intergalactic space fight), these themes were precisely what attracted teenage and young-adult audiences to the show. Gunpla capitalized on this and became a social phenomenon, as clubs dedicated to the series and fan meetings sprung up around the country. These early gatherings and clubs can be seen as a precursor to the Anime New Century Declaration.

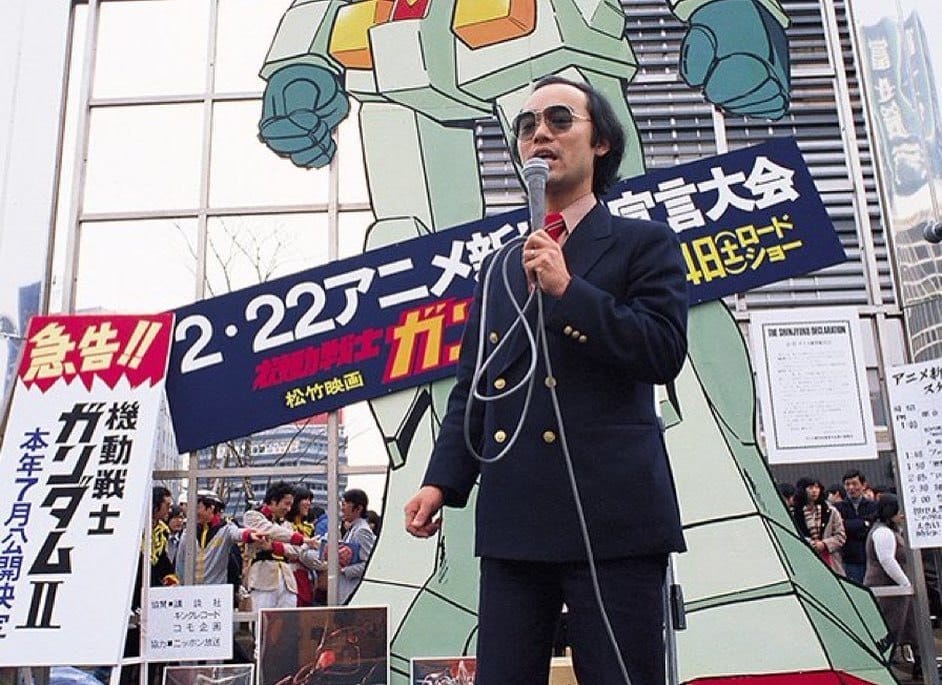

The event took place outside Shinjuku Station and would serve as a promotional event for the first Mobile Suit Gundam compilation. It was also a chance to bring together what was intended to be a small-scale embodiment of the phenomenon that had begun to grip 10 to 30-year-old people around Japan who had fallen in love with the Gundam franchise through word of mouth and reruns. If you get a few hundred fans together to celebrate the premiere of the film, it makes for good optics and shifts the promotional momentum in the movie’s favor... and might even help the series turn a bigger profit.

Roughly 20,000 people showed up to Shinjuku on that fateful day on 22 February 1981.

In the eyes of director Yoshiyuki Tomino, who had been at the center of the remarkable hurricane that was the Gundam franchise’s return in fortunes, the event would serve as an opportunity to celebrate the movie and declare the future of anime. As the Shinjuku Declaration that defined the event noted (read aloud to the waiting crowd), ‘we lay claim to our world opened up by anime and declare the dawn of a new century of animation’.

Anime had begun to evolve around the time of Gundam bursting on the scene, and though the anime itself was at least considerate the growing older audience for anime in Japan that would blossom in the next decade, the series had been held back by a production system that still relied on toys for survival. Anime like Gundam and Space Battleship Yamato attracted adult audiences and birthed the early era of anime magazines where fans could discuss and share their love for the industry.

劇場版ガンダム40周年。その特番にネット記事に出てた「アニメ新世紀宣言」の模様が映されてた。永野護氏と川村万梨阿嬢のシャアとララァ。お二人ともまだプロになる前だよね。このパネルガンダムが40年後1/1の可動ロボになるとは夢にも思わないよなぁ。ヤマトとはまた違ったムーブが始まった(^^) pic.twitter.com/WXHCFltX9Y

— 追跡戦闘者 (@masahitoSPV) March 14, 2021

At the same time, the kids who grew up on anime like Astro Boy were now adults with power over their own money and the ability to influence these industries, and were more than willing to spend money on series that appealed to them today just as Astro Boy once did.

Gundam captured this new and growing audience away from the public eye, and it was a surprise when fans turned up in their thousands for the New Century Declaration. Police were struggling to control the crowd and there were fears for a major incident if fans didn’t settle themselves.

It’s not that older fans weren’t acknowledged prior to the Anime New Century Declaration, but they were generally derided. With the most popular anime of the time being kids shows and thin advertisements, many looked down on the medium. Suddenly, with so many fans gathering to hear the architects behind their favorite series discuss the work that went into making the original Mobile Suit Gundam, these fans could no longer be ignored.

The event thrust underground anime fan culture into the public spotlight. In front of fellow fans and to the delight of newsrooms across Japan, some fans that attended the event in cosplay were speaking on stage and reciting their favorite scenes from the series. What was once a simple promotional event was suddenly a turning point in how anime fandom was understood and perceived by the wider general public.

Anime may had once been derided as derivative and childlike, but the fact that it resonated to people enough to bring them together, build Gunpla, and gather in groups large enough to close Shinjuku for a day, meant that it was something worth paying attention to. It may even be worth catering to this new audience of fans with more content like Mobile Suit Gundam. More series tackling mature themes, both in the mecha anime genre and beyond, were made to target this audience that further changed the views of the public that the medium was only for kids. And far from deriding the fans that turned up in droves, it made many realize that maybe this medium had a broader appeal than they first thought.

A New Century of Anime, 40 Years On

Gunpla is undoubtedly the phenomenon that saved Gundam, with the toyline alone now worth billions. But this well-worn toy story often obscures the arguably larger shift it had in public perception on a medium once derided for kids. Thanks to these toys and the Anime New Century Declaration, the medium was now firmly open to everyone.

The influence of that original Mobile Suit Gundam series, the New Century Declaration, and the cosplayers and fans who turned up to that event (some, like Mamoru Nagano, becoming animators in their own right) changed the direction of an entire medium forever. They declared a new century of animation, and in just 40 years, this small industry is now consumed by fans all around the world and has influenced people beyond borders and language barriers.

Mobile Suit Gundam may have changed anime, but I wonder if we’ll ever understand the true scale of how influential this series has been.

This piece was originally published to OTAQUEST on March 27, 2021