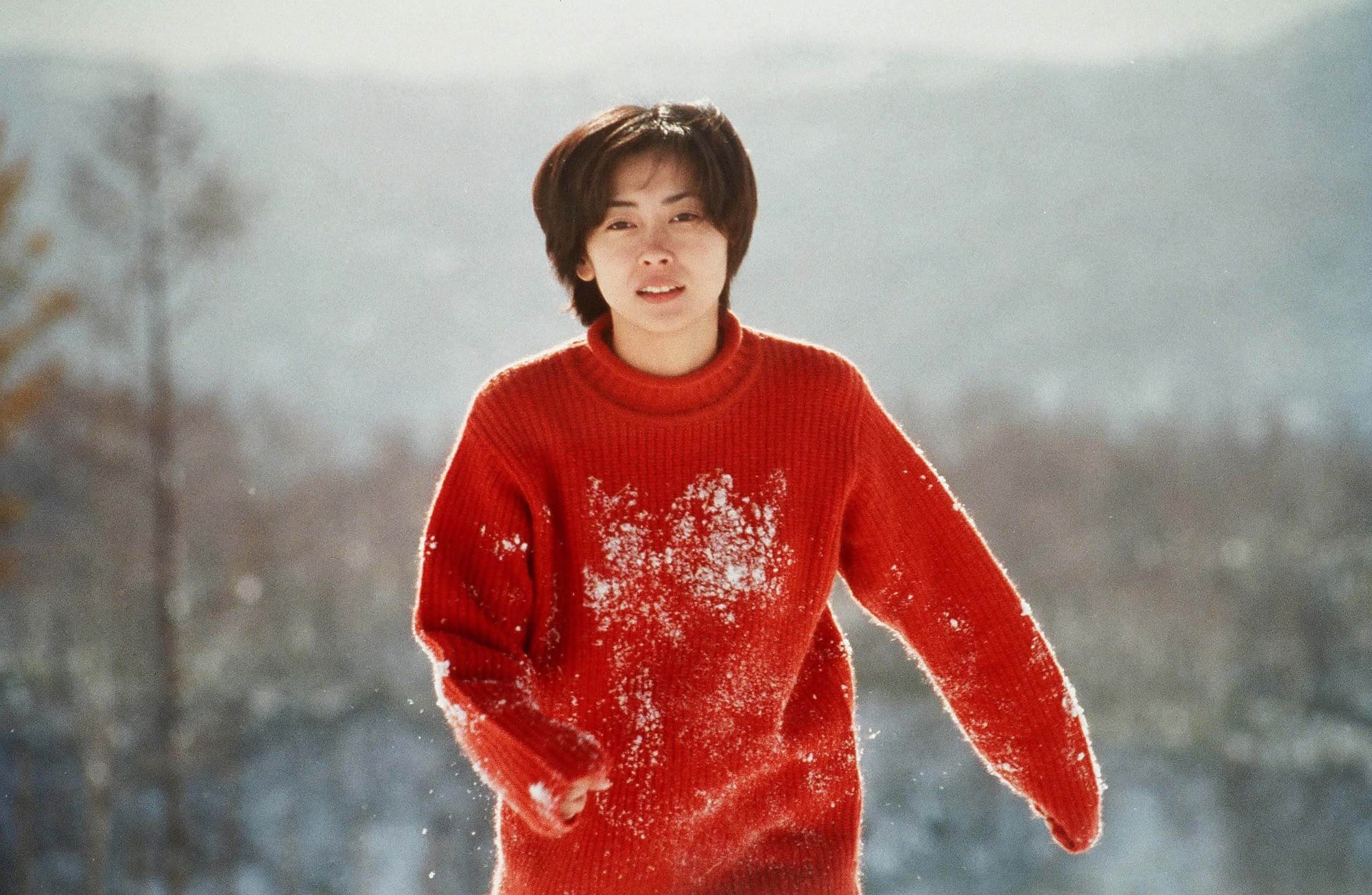

In the opening scene of Shunji Iwai’s Love Letter, Hiroko Watanabe (played by the late Miho Nakayama, who tragically passed away earlier this month), is lying in the snow, staring blankly to the sky with a sense of uncertainty and emptiness. Her fiancé passed in a mountain-climbing accident and she’s visiting the picturesque town for a memorial service two years later.

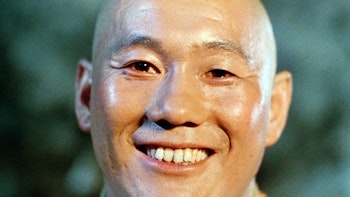

In the quiet revolution of indie creativity in 1990s Japanese cinema, this feature debut from Shunji Iwai was a quiet revolution upon its release. Not only did it introduce us to the talents of its director, one who would go on to create films like All About Lily Chou-Chou and Hana and Alice, but it elevated idol Miho Nakayama’s occasional acting appearances in films like Be-Bop High School into an acting force, winning awards as she established her prominence in the field for decades to come.

Idols making the jump to film and drama was nothing new, happening long before Nakayama and continuing even today (some idol talent agencies even produce their own films now to assist this process), but few have been quite as monumental as the statement made by this film. In a vulnerable role where Hiroko is still mourning the loss of her partner two years on from his death, finding his home address in an old yearbook and writing what should be a last letter to finally express her feelings and move on, we witness a layered and complex, mournful side of its star that floats mesmerizingly in this dreamlike space of memory and grief.

The letter is a simple one, being sent in her hopeful words ‘to heaven’ as a way of closing a book on a moment of the past. How is your health, it asks, before saying she is well. It’s not some long letter to express her pent-up emotions, but a final one-way contact to recognize to herself he is no longer alive. Instead she gets a response signed with the name of her lost partner. How did it get there when the house isn’t even supposed to exist anymore? What follows is a steady back and forth that revives memories of the past.

These letters are obviously not reaching Fujii Itsuki, her departed partner, from beyond the grave, and the letters are very real. This mystery respondent is actually a woman who was in the same class as her partner during her school days and coincidentally shared the same name. She even resembles Hiroko, with Miho Nakayama also playing Itsuki in both her modern-day and schoolgirl flashback sequences. The letters slowly reveal a new side to this partner that Hiroko was never fully away of before.

These memories recall a boy whose naming coincidences led to teasing and problems, but undoubtedly brought a friendship and connection to the two that lingered. A boy who was unique but somewhat introverted, someone who was bullied but also popular with some girls, and who hid a lot of himself from the world.

There’s a dreamlike essence to how we flick between childhood and the modern day and the perspectives of Hiroko and Itsuki. The childhood letters being addressed to the Hokkaido town of Otaru that they visit is a contributing factor, the snowy landscapes of both the opening memorial sequence and those taking place in a visit to Otaru feeling almost beyond our plane of existence in their endless landscapes of snowy white and soft visuals. Nakayama playing double duty with the roles of both sides of this letter exchange also make the whole thing feel very unreal, in a limbo state not unlike the shock the body feels as it tries to process the passing of someone closest.

As a feature-length theatrical debut for Shunji Iwai, the film fits with what we’d come to expect from the director before that point. Fireworks, Should We See It from the Side or the Bottom was a TV debut film that similarly ployed with a mix of down-to-earth realism and a beyond-reality dreaminess that in that film comes out in a time loop as the young Nazuna tries to run away with one of the boys in her class after finding she has to move due to her parent’s divorce. That film won him plaudits upon its original TV broadcast, giving him the profile and funding needed to make a feature debut.

Miho Nakayama’s more limited acting credits despite her popularity made her less of a known property when it came to trying to handle a more serious drama such as this. Not only that, to portray two very different characters and transporting her emotional delivery through the ever-changing lens of memory is a challenging role. Yet it is precisely this performance that allows the film to sing, lyrically transporting us beyond the logical reality into the emotion-driven confusion of love and loss and the ways in which our memories of the past change in time, and transform how we view the past and present. She won the Hochi Film Award for Best Actress and was nominated for and won countless others.

Love Letter is a nostalgic look back on adolescence that feels universal and envelops like a warm blanket while reaching deep inside and leaves you wandering the world thinking of the people and places that helped you to where you are now. How the past memories shape who we are now, and must inevitably be understood and embraced to move forwards. It’s a love story to a point, but its universality comes in how it reaches beyond that to try and understand an essence of the pain that to love is to let go, to meet is to say goodbye, and to know is to be changed.

That is driven by Nakayama’s performance, establishing her in a way that she carried to future work. It’s also a feeling that allowed the film to be embraced internationally, earning it an even greater legacy beyond the warm memories it holds in Japan as one of the most enduring films of that decade. It received a limited US release and won the Audience Award at the Toronto International Film Festival, but more notably the film was a big success in East Asia, including in South Korea. Historic tensions meant that only shortly prior to the film’s release was it allowed for cultural imports to enter the country, and the film caught the attention of Korean audiences to become the 10th highest-grossing of that year in the country.

After Nakayama’s sudden passing, lots of thoughts began to run through my head. The first and most prominent, however, was shock. As Patrick recently put it here on scrmbl, Nakayama created one of the best song catalogs and filmographies any artist has ever managed in Japan. Her music has transcended generations and remains beloved, as does her acting in Love Letter. The news of her death propelled the film to being one of the most-watched on Netflix.

A stunning melancholic, warm view of grief and memory, a show-turning performance, a statement from an exciting director who continues to impress. Love Letter is special.

Classic Film Showcase shines a light on historical Japanese cinema. You can check out the full archive of the column over on Letterboxd.