Gisuke Watanabe (Kyozo Nagatsuka) is a lonely man. After a fulfilling life, the retired university professor and widow winds away the days writing the occasional magazine column on French literature, meticulously prepping meals and occasionally meeting old students and giving talks. This routine no longer excites him the same way, however, and his dwindling savings paint a worrying future. The solitude was once a self-chosen thing, even a welcome pace, but it serves now to be little more than fuel for the man’s anxieties and old-age insecurity, particularly once an anonymous email of an approaching enemy sets in motion a twisted tale that serves both as a character study and considered, deep exploration of the frenetic cultural zeitgeist of today.

Teki Cometh finally hits Japanese cinemas after becoming a critical darling following its world premiere at Tokyo International Film Festival at the end of last year against films like She Taught Me Serendipity. The film took the top prize from the jury in the event’s competition, and it’s easy to see why. During my own screening at the event, the tension the film built in its subtle blend of thriller and conspiracy in a black-and-white palette and claustrophobic framing befitting of the descending confusion of a declining man in surreal times, was unlike anything else at the event, barely leaving my thoughts in the months which have followed.

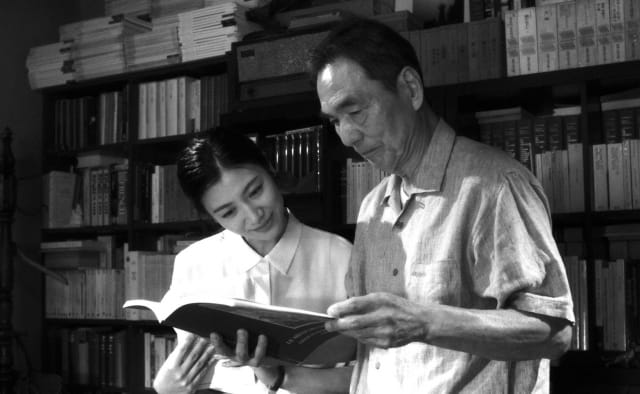

Considering what’s to come, Watanabe’s life feels almost tranquil in the film’s earliest moments. It’s hard to compare this film’s journey to a single inspiration, but to play to the retro aesthetics the film embraces amidst the monochrome visuals and the traditional ideas of its main character, I found myself reminded of a bizarre combination between human and family dramas of the 50s like Yasujiro Ozu’s Tokyo Story, mashed with a touch of the macabre like in Hitchcock’s Rear Window. Teki Cometh begins structured and ordinary, if morbid. Watanabe has an old student who helps re-landscape his garden, while his repressed desires as a widow surface in the flirtatious exchanges with another female student.

Otherwise, life is a ritual in its unchanging uniformity: sleep, cook, write… and after checking how much of his retirement is left, planning death on his own terms.

We place ultimate trust in our brains and its thought process because our sense of mind and self is the only thing that can truly understand everything that makes up who we are as a person. A partner, a friend, a colleague, no matter how close, they can never understand your deepest insecurities, urges, regrets and hopes, not for a lack of care but because they themselves are not experiencing it. Yet Teki Cometh’s greatest strength is how it plays with this assumption of self-knowing and our own assuredness to this fact to place us in a state of never truly knowing what is real or not by the end of the film. An unreliable mind becomes a jittery, erratic, compulsion-driven machine of madness and the film itself takes our understanding of reality and twists it beyond recognition.

‘The enemy is coming’, the email states. Nothing more, and it’s not a clear or obvious scam. If anything, befitting the ways older people have used the internet in an almost-unchanging fashion since the 2000s, it feels more like a Facebook engagement post praying on the insecurities of the old and lonely, or a chain mail sent between geriatrics like pass the parcel. Who is the enemy? What is the enemy? Why is the enemy?

As it gnaws at the mind, life continues. Meals continue to be prepped, the articles continue to be wrote, at least until they’re suddenly halted as a magazine reforms under a changing print media landscape. Life otherwise proceeds as normal, but the question of the Teki never goes away. Emails keep coming, even becoming more erratic and alarming over time. Amidst it all, the water well being reopened in Watanabe’s garden landscaping feels like an ominous, never ending descent to darkness, equivalent to the mind of its owner.

Nothing seems to make sense for both Watanabe or the audience, and it can be difficult to parse between fiction and reality in the man’s aging mind as dreams and hallucinations intensified by panicked anxiety over the repeatedly-gesticulated enemy intensify. His health declines, forcing him into hospital for a colonoscopy where thoughts of his female former student transform a routine procedure into an almost-sensual BDSM-esque display of gratifying humiliation.

Before it descends too far, a message does begin to reveal itself. Warnings of the enemy break from the confines of the screen and the online conspiracy to have real consequences. They turn up in his mailbox with warnings of an enemy from the north, fueled further by fake news spread between him and his similarly-aging neighbors about the increased dangers brought about by the ‘invasion’ of these enemies that shatter the peace they once enjoyed. These enemies - refugees, minorities - are causing social unrest, ruining society. They’re even going to have to bring about martial law in order to quell this danger, lest they overrun society and replace us.

In our modern climate, the internet has made it easier than ever to pit us against one another. Without a person to look at in the eye while having these conversations, it’s far easier to create a faceless enemy when even your ally and the person with whom you talk with is little more than words on a screen. Couple that with a lack of understanding about the online world and its propensity for spreading misinformation, turbocharged by our protagonist’s brain no longer being as sharp as it was in days of youth that can easily dwell on such fears fueled by isolation, it’s no wonder the whole world feels like it’s gone a little crazy.

The enemy, the Teki, has cometh. But do they even exist? Or are they merely ourselves, staring us down in the mirror as we tear ourselves, our lives and strangers to shreds based on lies?

Teki Cometh thrives on creating a lens into a waning mind as disorienting as the world we live in now. Even the most rash decisions that appear obviously ludicrous when seen from an outside perspective make sense when you’re trapped in the eye of a hurricane constructed from the walls and anxiety built from our own isolation and the lies we’ve taken as gospel. It’s a compelling, singular vision that only works thanks to the masterful direction of its director Daihachi Yoshida and lead actor Kyozo, who deservedly won a prize for his embodiment of this teetering old man alongside the director.

Despite the world constructed by its finale, it’s hard not to feel a sense of sadness and pity for the decline witnessed in Watanabe’s character. Reflecting on his accomplishments against the contrast of his current state, the resurfacing of his past amidst these manic episodes feels like the manifestation of a fear of losing the joys of the life and accomplishments that made his life worth living until that point. The enemy, it appears, is created by a desire to save the past, a memory relived because a fond memory is now overtaken with fear of it being lost forever.

There’s something tragic about that, really.

Japanese Movie Spotlight is a monthly column highlighting new Japanese cinema releases. You can check out the full archive of the column over on Letterboxd.