Happyend begins with a warning. “The forces trying to confine people to old frameworks are loud.”

This may be a film set at an undisclosed date in the future, ominously stated as the year 20xx, but this is no sci-fi-infused moral message. This is more urgent, a warning of the present day, present time, and a cry to stand for humanity in a society of surveillance and unreality, and against the indifferent powers that be. That being said, with such a thundering and angered call to action shouted on screen before you’ve long sat in your seat, you may not expect what happens shortly after this opening scribe: silence. Then, a party.

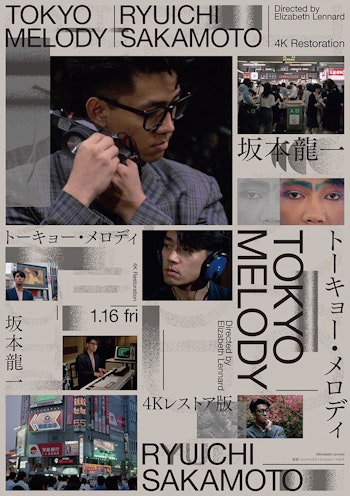

Let's step back. Happyend is the fictional directorial debut of Neo Sora, the half-Japanese and half-American son of the late musical composer Ryuichi Sakamoto. Having directed the music film of his father’s final musical performance in Opus, this marks the first fiction work by the young director and one that establishes him as a voice to watch over the coming years following its recent Japanese release and prior appearances at Venice and London International Film Festival, among others.

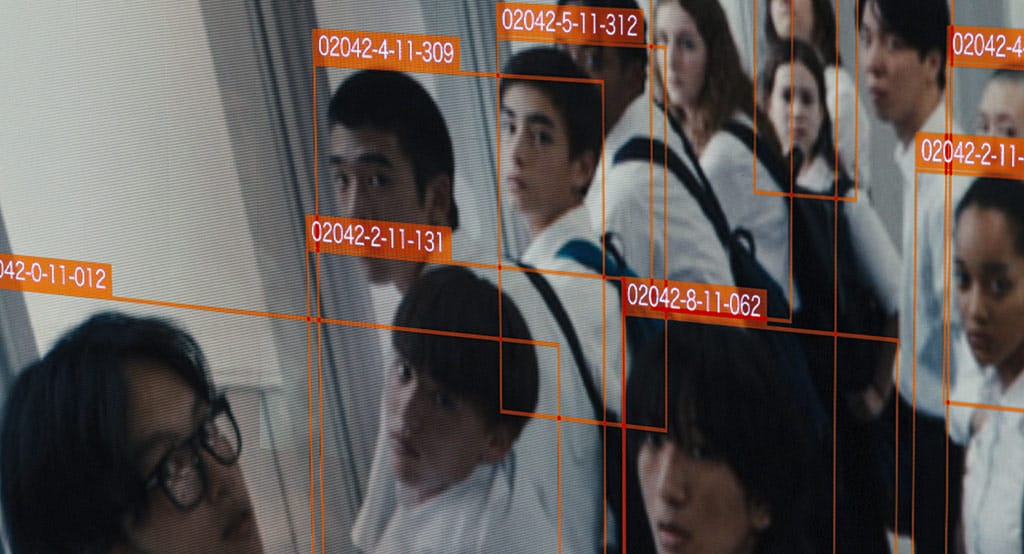

In this undated future Tokyo, the air is tense. An emergency declaration is in effect after a series of foreshocks warns of a stronger earthquake that’s likely to destroy the city. Yet the quake never comes, the warning system is full of errors, and the declaration conveniently provides overwhelming police and surveillance powers often used in discriminatory and excessive ways against the youth and those with foreign lineage (whether immigrant or born in Japan) that aren’t deemed ‘Japanese’. Police can use facial recognition to get information on a suspect with a simple photo on their phone, technology not as a liberating but controlling force to crack down on opposition, weaponized to perpetuate an unjust status quo. It shouldn’t be surprising that in an attempt to escape surveillance, the younger generations are almost entirely absent of phones themselves and other similar technology.

Despite it all, we party. When injustice occurs, we at least try to fight back. Because what else can we do? Let it be said here, this is no post-apocalypse. This is the slippery slope of today, and how to fight against it.

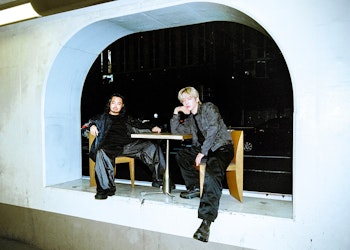

Yuta and Kou (Hayato Kurihara and Yukito Hidaka), alongside the rest of the so-called Music Research Club including Ata-chan (Yuta Hayashi) and Tomu (Arazi, one of a few black and non-Japanese characters in a welcomingly non-homogenous cast within a Japanese film industry far less diverse than it could or should be), are two rowdy kids in their final months before graduation. The questions of what’s next, alongside the rising tide of xenophobic nationalism that in this context is reminiscent of anti-Korean sentiment for the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 but is certainly not missing in modern Japanese society, is beginning to pull these friends apart.

These are the kids who are trying to party amidst it all by attending this illegal rave inside an abandoned warehouse, each drifting in their own polar directions in reaction to a raid on the facility as the tides of life shift below their feet.

Yuta is rich and aloof, more free to stand up and cause chaos because he has the money and privilege to generally avoid issues. Kou is a Zainichi Korean focused on getting to university, a status and dream that keeps him firmly under the thumb of this newly-sought power. While avoiding melodrama to keep its politically-motivated awakening at the core, it’s Yuta’s prank to flip the principals car that sees him take advantage of new surveillance technology and the emergency powers to install facial-recognition cameras across the school that not only keep track of everyone, but even ranks their social credit and displays it on a large screen.

It’s called Panoptny, like a panopticon, an all-seeing eye. Subtle it is not, but so what? The school president is certainly abusing his power by spending large amounts to install this hardware to catch a prankster, and certainly isn’t considering the community of the school. It contrasts protests against the government outside the school walls - the film rarely leaves the school grounds, but when it does the divides in society only become clearer as protest contrasts events like Kou’s parent’s restaurant getting racially vandalized to label it as ‘foreign’. The point is not to be subtle about what surveillance is being installed, now how it reflects our present-day all-consuming grasp of technological data collection.

As noted at the start of this piece, this is no sci-fi retelling, but a more obvious warning. This friend group, less fractured but no longer speaking in one voice, is each reacting in their own way, some coming together with other students to try and object to this new technological invasion. A stand-off with this principal is inevitable, a face for the government within this story and our world alongside a reminder that action, not words, conducted outside the systems that oppress, is what leads to change. When the moment comes, will you take that stand or simply allow control to suffocate the truth.

This is an at-times frustrating film in how it often feels torn between the exasperated retorts of a left-wing creator warning against techno-fueled fascist uprising in our world fueled by disinformation, surveillance and the uncertainty and gentle shifts within the coming-of-age framework. These are interlinked ideals, but they never quite gel as well as I would hope within the film. As it reaches a conclusion, it never quite coalesces these two sides, either.

Even with this at-times disjointed script, it’s message shines through, fascinates, and is the overwhelming idea that dominates the mind walking out of the theater. It even weaponizes the tropes of Japanese cinema to emphasize this. School dramas, coming-of-age stories, they’re nothing new, but using it to discuss this creeping techno-fascism embodies the reality that our response to this wave of surveillance will decide the fate of the future.

The future is in the hands of Gen Z and Gen Alpha, the generations growing with this technology and first-hand survivors of this new reality. They’re the generation coming of age, graduating school or in their 20s and experiencing their first years of working life, building the worldviews that will decide the future. They are Yuta and Kou.

We are Yuta and Kou.

So what’s next? We party. Because to party is to hope, and to hope is to have a reason to live and fight. With that, you can change things. You must change things. You must.

Japanese Movie Spotlight is a monthly column highlighting new Japanese cinema releases. You can check out the full archive of the column over on Letterboxd.