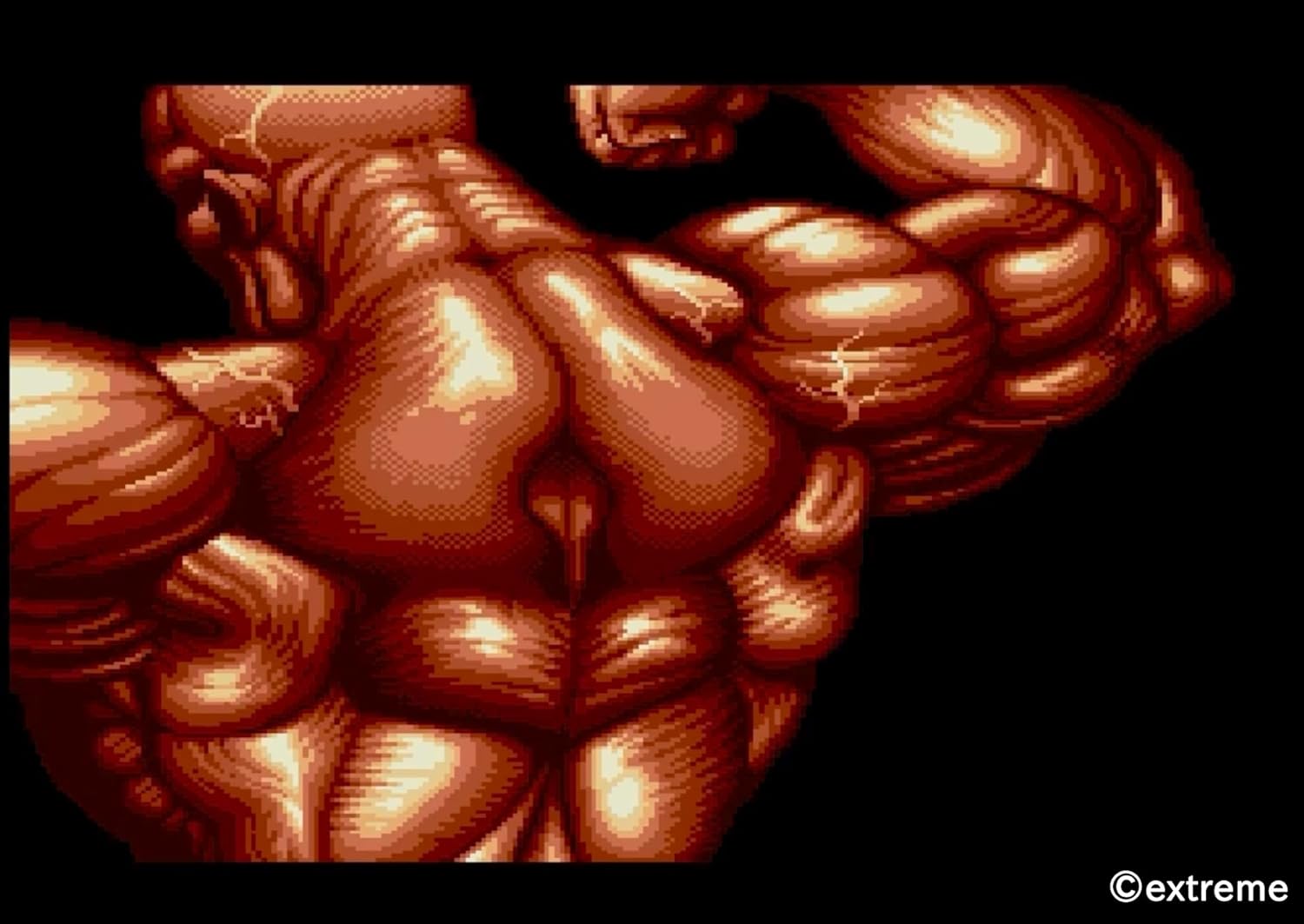

For years, it’s been easy to ridicule the Cho Aniki franchise. It’s been the running joke online to do exactly this, to the point the game has become little more than an experience to point and laugh at the extreme homoeroticism on display from just a glimpse of its near-naked bodybuilders on the cover. It’s likely few who join in the joke have ever played it, the experience and legacy of this franchise obscured by its outsized reputation.

Cho Aniki isn’t a one-off, silly shooter on a decades-old console, its a series whose initial success paved the way for numerous sequels and ports over the coming years. There was genuine love for this unique shooter that allowed it to be remembered beyond the walls of its own development studio. The games are fun, and the memorable off-the-wall visuals are only possible thanks to some incredible technical prowess that technically make this a surprisingly advanced game for the era.

Considering it is these absurd-yet-well-constructed visuals that are a large reason for the continued relevance of this series, it would be unfair to dismiss the sincere love that made these games possible. With a new remastered collection out now on Nintendo Switch, let’s recognize this title’s genuine achievements.

It’s ok to laugh. It’s hardly like the games aren’t self-aware of how bizarre these oiled-up muscle men are, and even the new remaster does everything to obscure the minimal spandex worn by these handsy individuals proudly adorning the cover, abs and biceps on full display. While the moment-to-moment action of Cho Aniki is your standard side-scrolling shoot-‘em-up fare, there is an obvious punchline. Enemies have phallic imagery, cannons will fire out other muscle men as projectiles. You shoot bullets from your ripped pecs.

Yet it never reaches a point of distaste. It’s camp, filled with voyeuristic masculinity and beefy men for the sheer joy of it all. You’re laughing with, not at, Cho Aniki.

The series has its roots on the PC Engine, before later making its way to everything from the Saturn to the PlayStation to even the Wonderswan. While there exists a story about bodybuilders saving the world in a battle against an army of invading nearly-naked men seeking protein powder for their homeworld, it's more of an excuse than anything worth taking seriously, a justification to insert these men into loving homages to R-Type and Gradius. There’s even similarities in boss designs between this game and these classics, bar Cho Aniki's visual quirks that lean into bodybuilding culture and even biblical imagery.

Despite its reputation, in its original outing, the more erotic displays of muscle men are far more toned-down, often only embracing a more sexual and homoerotic nature in subsequent installments. While I won’t pretend that this is the best shooting game in the world, what was achieved by the team at Masaya in 1992 is nonetheless impressive. Parallax scrolling across multiple background layers with an overload of sprites on screen at once is a technical feat that similar titles of the era struggled to achieve, all effortlessly done without much in the way of slowdown.

Art in cutscenes is similarly impressive, with immersive shading even bringing genuine tension to its otherwise-silly nature.

It’s made with love, which also extends to its soundtrack. Indeed, where the game disappoints is in its length. I wouldn’t call myself the most competent when it comes to shooting games, yet my middling skills at side-scrolling and doujin shooting games even 8 years ago were enough to clear a version of the game in a single afternoon. I never finished Cho Aniki: Kyuukyoku Muteki Ginga Saikyou Otoko which I obtained through the PlayStation Network rerelease on PS3, but that was more a result of not playing the game enough to finish it as opposed to any genuine challenge it posed.

Without varied difficulty, the experience becomes stale and lacks a reason to return when the novelty wears off. There’d be little reason to think about it beyond the few short hours it takes to finish the game were it not for those muscles.

Yet, it endures. The developers referenced it in other titles they made, like Langrisser. Sequels to the original Cho Aniki, while typically less beloved than the original, continued to be made in a testament to the unique nature of the game that makes it enough of a novelty to keep bringing people back. This new Nintendo Switch remaster, while somewhat pricy at ¥7,500 for just two of the original games, is testament to its endurance. Scans of original booklets, soundtrack compilations and more included with the release are a love letter to a game that’s far more than the butt of a joke.

These may not be the best shooting games you’ll ever play, but that’s fine. To only remember the very pinnacles of a genre obscures the experimentation, creativity and personalities that turn a medium and production into a culture worth preserving. Cho Aniki is a tribute to muscle and queer culture as much as it is a camp, dumb, too-short shooter with middling difficulty, put together by talented developers who elevated silly designs into something intoxicating and memorable.

So yes, it’s easy to ridicule Cho Aniki. But there’s more to this game than a punchline.