An old song suddenly blowing up on TikTok and finding a new audience is old hat in the 2020s…but sometimes, the tunes going viral via short-form video still surprise.

Take, for example, a relatively obscure b-side from a ‘90s Japanese artist with a much more acclaimed discography being embraced by younger generations who turn it into his most played on subscription streaming.

The “Typewrite Lesson” trend on short-form video from this past summer found users taking the song of the same name by Cornelius — the solo project of Keigo Oyamada — and using it to soundtrack a variety of videos, most of them leaning towards the romantic or melancholy. Removed from any context, the meme-ability of the clip makes sense, thanks to a distinct rhythm and male/female vocal combo. Yet within the history of the creator it’s a baffling development.

Perhaps though, that’s fitting. Since starting the project in 1993, Oyamada’s solo effort has played a central role in shaping the out-of-time sound of Shibuya-kei, helped to spread experimental electronic pop to the outside world and found itself caught up in one of the biggest scandals of the 2020s so far. An out-of-the-blue TikTok trend feels like a development apt for Cornelius, which has never stood still and always up for surprising listeners over the last three decades.

Brand New Season

By 1991, Oyamada had become a poster child for “cool” in Japan thanks to Flipper’s Guitar, his indie-pop-pastiche project with Kenji Ozawa. Yet after the pair split up, Oyamada took several years away from the spotlight before re-emerging under the name Cornelius in 1994 with solo full-length The First Question Award. His first by himself wasn’t a grand departure from his previous outfit, but more like a continuation featuring a mix sturdy indie-pop fun (“The Sun Is My Enemy”) to more eclectic experiments in foreign sounds of yesteryear, of varying quality (“Cannabis” just kind of meander about, a tourist on a beach not sure what to do next).

Follow up 69/96 pointed towards a much more exhilarating sound. Embracing a heavier rock vibe while still swirling together sonic ideas hailing from disparate places and times, Oyamada made something that sounded largely unlike the chipper twee leanings of Flipper’s Guitar, revealing a more experimental studio wizardry lurking within Cornelius. As writer W. David Marx — the best chronicler of Oyamada’s work and Shibuya-kei at large — wrote, 69/96 showed “his diversity of musical knowledge could work to push his albums beyond a commercial necessity and into a rumination on the history of pop.” He would truly dig into that soon after.

New Music Machine

Released in the summer of 1997, Fantasma isn’t just a high point for Oyamada, but one of masterpieces of all Japanese music in the 1990s. This studio spectacular has inspired plenty of glowing reviews — here I point towards my own for Pitchfork, trying my best to not just regurgitate all of that one — so it can sometimes feel hard to say something new about it. Yet even just hitting its major accomplishments one more time can be helpful.

Fantasma is Oyamada’s ambition meshing perfectly with his creativity to create something like a sonic amusement park ride, one working best when listened to from front to back. If his previous album found Cornelius learning how to celebrate the entire history of recorded music in all its nooks and crannies, his opus finds him using that same timeline as material to construct something new. This is where the previously guitar-loving Oyamada realizes his strongest instrument is the recording studio itself, using every trick possible to create a sound spectacular standing as Shibuya-kei’s artistic peak. The best way to experience today is the same as then — hit play and just enjoy where Oyamada takes you.

If there’s any new development to Fantasma fanaticism, it’s how a new generation seems just as interested in the bonus tracks, collected in a 2010 release you can hear above. That’s where the viral “Typewrite Lesson” comes from, and that one offers a taste of what is to be expected on these rarities. This is Oyamada in a much more sample-focused state of mind, drawing from film soundtracks, The Powerpuff Girls, instructional records and more (while being rounded out with some heavy-hitting names offering remixes). Whereas the album proper is a trip, this is more like a practice, Oyamada playing around and showing what he’s capable of before ratcheting it up a level.

Another View Point

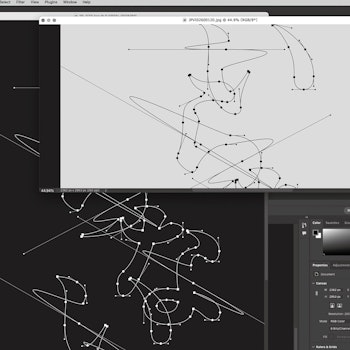

With the arrival of the new millennium, Oyamada decided to take the Cornelius project in a new direction. Whereas Fantasma reveled in the Technicolor possibilities afford by sampling and a studio, 2001 follow-up Point found him moving in a more methodical direction. He became much more interested in audio texture, allowing touches of his past Shibuya-kei to sneak in but mostly becoming more interested in precision than collage.

It’s still an enjoyable album, but one presented in an entirely different mode than what came before it. “Point Of View Point” is start-stop stuttering, utilizing the channels on a pair of headphones not for a whirlwind but something more specific. “Drop” incorporates water sound effects as part of its chug, while even a rocker like “I Hate Hate” treats bursts of feedback like carefully timed pyrotechnics rather than spontaneous bursts. Oyamada becomes much more focused at this point.

His next album, 2006’s Sensuous, offered a more diverse interpretation of this new mechanical mindset. There’s a touch more twinkle and chime to the songs here all while still sounding like they were plotted out perfectly on graphing paper. “Fit Song” follows the same start-stop of Point, but there’s something more playful in the way it struts along. “Breezin’” and “Wataridori” are precise instrumental numbers that manage to sound lithe and a touch more free. There’s also dizzying moments like the out-of-body sound experiment “Like A Rolling Stone” and the earnest closing lullaby “Sleep Warm,” featuring Oyamada’s voice smudged with digi manipulation.

During this period, Cornelius live matched up the songs with perfectly synched videos playing behind Oyamada and his band, resulting in an audio-visual feast. It was impressive to see back in the late 2000s when he brought it to the States — and made the moments when he broke away from all that precision to let his older songs rip the order apart even better.

Not-So-Mellow Waves

By the time Oyamada’s Cornelius project returned in 2017 with Mellow Waves, he had established himself as a veteran of Japanese music and someone TV networks, museums and companies could turn to for a snazzy-sounding soundtrack. Twenty years since the kaleidoscopic thrill ride of Fantasma, and he was now in a more reflective space, albeit still interested in playing with the texture of sound.

Mellow Waves is Oyamada grappling with aging, the songs lyrically centered around memories of times (and people) now gone, while at one point he sends a metaphorical letter to a “future person” to see if his music remains in a time where he’s long gone. While being a touch more subdued and introspective on the words front, the music around it was among the best he ever made, turning the guitar melodies and precise beats of his 2000s output into something a touch more melancholy here, all while still fitting in feedback freakouts and, on “Surfing on Mind Wave pt 2,” an ambient wash showing how his collage technique could carry over to something closer to new age.

It was a late career triumph, and a reminder of his artistic legacy. In a lot of stories, this would be a triumphant ending. Yet Oyamada’s past was about to crash into his present.

During the 1990s, Oyamada gave interviews to several music magazines at the time where he boasted about bullying classmates while in school — including some with learning disabilities. Published but mostly overlooked or celebrated during a decade big on “bad taste,” these quotes long circulated online, popping up in Japanese music circles but never turning into anything bigger. That is, until Oyamada became connected with one of the most controversial events in modern Japanese entertainment history.

Let’s not dwell on the fiasco that was the 2020 (errr, 2021) Tokyo Olympic Opening Ceremony, an event featuring multiple controversies in the months and days before it happened. Basically, it snowballed, with an already unpopular event resulting in everyone involved basically having their respective past transgressions brought up. So was the case with Oyamada, serving as the composer for it but whose bullying quotes spread further than ever, forcing him to resign from the position and canceling a whole bunch of other activities alongside being dropped by programs he worked with.

It was a mess but a necessary reckoning, albeit one that resulted in Bill Maher coming as close to the Shibuya-kei universe as one could imagine. Without getting too bogged down in what happened next, the story didn’t end there, as Oyamada did an interview a few months later shifting the blame to music journalists, and a whole movement to basically “uncnacel” him emerged. If you have the time, streaming channel Dommune’s two-and-a-half-hour program dedicated to clearing Oyamada’s name is a fascinating watch, especially if you have any interest in how the country’s media and approach to social topics goes.

Recent Tide

Eventually, Oyamada got back into the swing of things by performing at festivals domestic and international, while also starting to release new music. Yet he seemed to be moving towards the dreamier, escapist parts of Mellow Waves. His follow-up album saw him turning even more inward, reflecting on love and life, with very little outside of it getting in the way. Perhaps an intentional move, given how much came down from there in the years prior. He drifted further into his mind palace with Ethereal Essence, his full swing into new-age vibes, with the synth melodies of his Aughts output now turned into sonic sauna sessions (one song here namechecking them, in part as it was made for a TV show about sauna). Oyamada seems OK being detached from the world around him, opting to sink further inside himself.

Which makes something like the “Typewrite Lesson” moment this year feel welcome. By what seems like total luck, a song from his Fantasma era — where he was letting listeners into his head in a very different way — has connected with a new generation, and even if it’s just the soundtrack to memes, it’s allowing a style Oyamada has drifted away from to find a new audience. There’s a lot of baggage that comes with the Cornelius story, but in the end, those “future people” found a way to keep his sound going.

Five Essentials

“The Sun Is My Enemy”

While closer to Flipper’s Guitar’s indie-pop sunshine, “The Sun Is My Enemy does feel like a highlight in this mode for Oyamada, and a fitting end to that era.

“NEW MUSIC MACHINE”

Choosing individual songs off of Fantasma feels weird, as it’s a work demanding to be experienced as a whole. If you forced me to surgically slice out something, it would be the driving power-pop of “NEW MUSIC MACHINE.”

“Drop”

Most of Point can feel like a sonic science experiment, so let’s highlight a song using an actual element to round out its sound. The water samples here make for a wonderful counter to Oyamada’s main groove.

“Music”

As warm as Oyamada’s 2000s sonic experiments got, topped off by being a nice bit of self-reference as it details the act of creation.

“Sometime / Someplace”

Reflective and introspective Cornelius has plenty of gems, but it’s nice hearing something with both a tenderheart and killer guitar bursts.