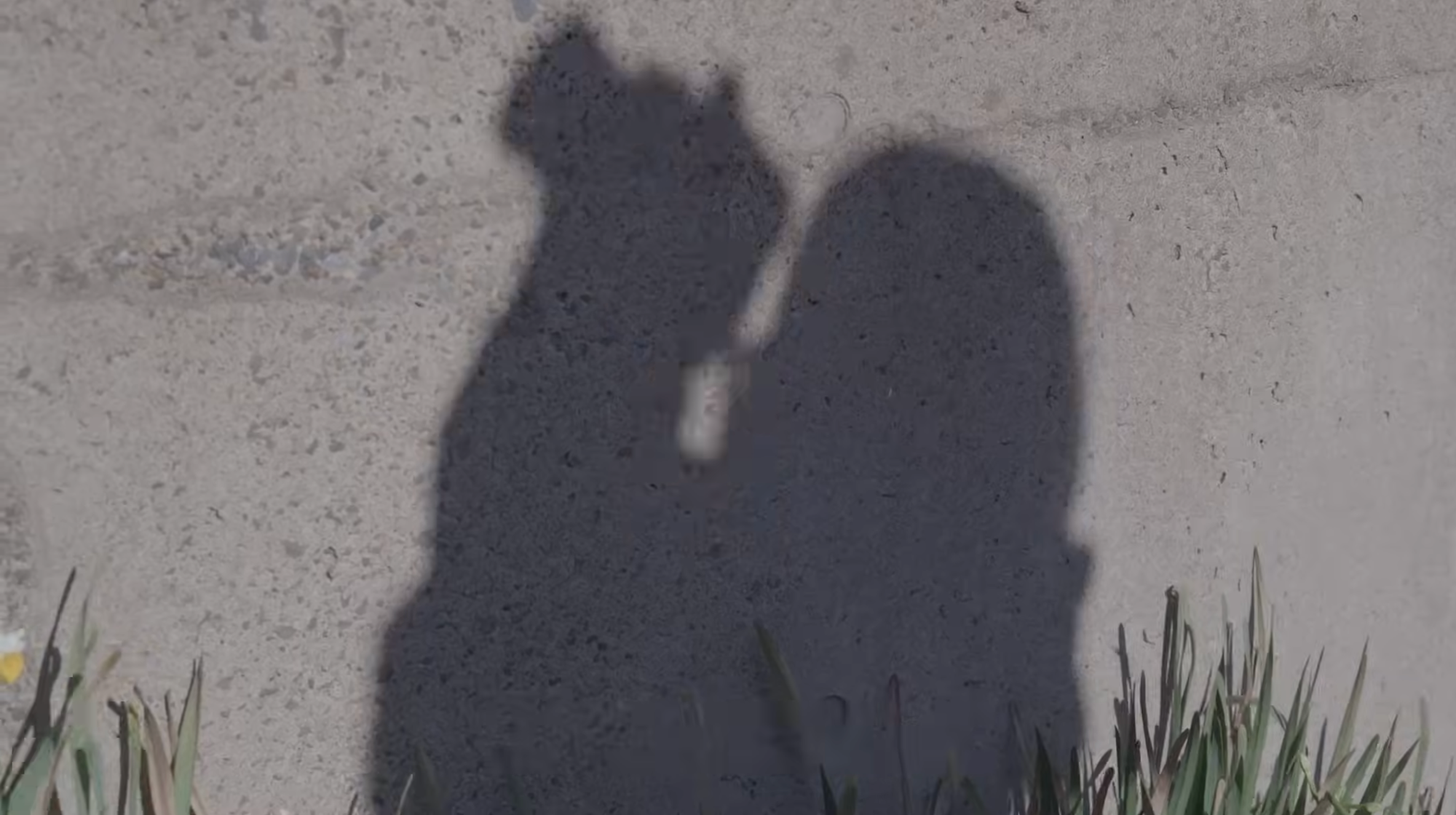

Entering my screening, I was provided with a postcard with a message from the filmmakers of A Big Home that was repeated both at the start and following the credits of the film. This is a documentary about the children and the lives of kids living in care, as well as those who have become adults and are seeking their independence as adults. These are sensitive circumstances for the kids featured to show their face and talk about their lives. In return, alongside only allowing the film to be shown in cinemas with no plans for a streaming or video release, the request is made not to share their name or faces on social media or elsewhere, to maintain their privacy as they continue to find their place in the world.

We will be respecting this request, and will refrain from discussing some specifics of the lives of the children featured in the documentary, nor will we use the names provided throughout the film.

The fact this film exists, with such a simple request as they show their face and let us into their lives, is testament to why these stories matter. To still show your face with naught but a non-binding request for privacy and respect between those in the home and the filmmakers, and in turn the filmmakers and the faceless audience, is to welcome us into A Big Home, and the found family built within the walls of care. It’s not perfect for these kids. But it’s a source of love and joy nonetheless.

According to the Japanese government as stated in the film’s opening, roughly 42,000 kids require a form of social care. This is not necessarily the same as an orphanage, with half of these children including those we see in the film living in a children’s home. Unlike an orphanage, reasons for children living in such circumstances can include parental death - one of the younger children we focus on talks with a brave face but telling sadness of their parents dying at the age of three - but could be for reasons such as domestic abuse, illness, financial issues, or other reasons.

They have no control over these circumstances, but the discrimination and ostracization that can face those who grow up in such facilities is an issue, almost certainly contributing to the prior warning.

Yet despite their circumstances and the understandable anxieties that come with it, there is clear love for the unlikely family they have fostered here. It’s almost like a giant share house, with each kid having their own space but large shared facilities to eat together. We get a very enthusiastic tour from a young girl at the start of the film with a constant smile and excitement that greets staff like loving family.

The home we focus on, based in a nondescript area of Tokyo, is certainly one of the best springboards these children could have for the future in such a situation. The religiously-affiliated home offers plentiful food, love and support from the surrogate parents that are the staff who must teach these kids independence for their post-18 lives. With large parks and rural sprawl nearby, there’s space for play beyond the confines of the home, too.

Rather than focusing on the circumstances that bring the kids into this care in the first place - to do so is to touch on broader societal ills far beyond the scope of the film - we focus on what it is for those who have to make the most of the circumstances they find themselves in now. This takes the form of interviews with each kid as we follow them on their lives, most in their teens and some on the cusp of moving out and living beyond the facility. Dealing with the general anxieties of school and life as a teenager (we see close members of staff of the facilities attend one girl’s school graduation ceremony so she won’t be alone for it), what is it actually like to live in such a unique situation?

While this sinks the film into a routine of 10-15 minute chapters that follow each kid exclusively and individually before moving on, rather than blending these stories together to capture the community of these homes, it’s insightful nonetheless. These are very self-aware kids. They know their home ‘isn’t normal for most other kids’, as one puts it, but despite the challenges this brings they love the chance to have these large families and ‘brothers and sisters’. Even if privacy concerns mean we don’t learn too much beyond vague descriptors of how the children got here, the scars remain.

So does perseverance, which is moving to witness.

These segments have a fine line to bridge between informing audiences and retaining a sense of love that avoids reducing these kids to case studies. Ryo Takebayashi, the director, has previously filmed a documentary called Bookmark 14 that follows a middle-school class for one year to show the plain, ordinary life of a teenager, retaining the sense of idyllic observance you would expect from that film. Yet the director’s other film was the clever time-warp comedy Mondays: See You ‘This’ Week.

The point being, this is very much a director who eschews the idea of journalistic-style clinical reporting for an emotional capturing of life that respects they’re human beings not exhibits in a zoo, though it can feel as a result we don’t get too far beyond the surface with some children on the unique challenges of living here.

It’s why we get the most insight on what growing up in such a large home like this does to the perspective of these people as we transition away from those living in the home to those taking their first steps into life beyond. For one 18-year-old resident, they decide to take on volunteering in Nepal in a foster home, and we travel with them as they talk through an interpreter to these kids. The woman volunteering learns much from these young kids that mirror her own circumstances 10 years prior, and the happiness they feel in contrast to the strictness of Japanese life.

Perhaps more probing into some of the emotions expressed by these children could be welcome, but it’s hard to critique. This is clearly made with a sincerity for the wellbeing of the child that shines, from the sketched artwork of the poster, the careful soft lighting that bathes warmth on every facet of the home. Small memories, like learning to tie a tie or the father and son-like conversations with the male staff and kids about baseball, are elevated and a joy to witness for the normalcy it brings these kids.

For producer Takumi Saito, known more as an actor for his many lead roles including recently in Shin Ultraman and also starred in the recent Netflix drama The Queen of Villains, he proclaims the desire to tell this story as the fact that ‘perhaps this is why I make films’. Bringing a voice to those without it, in a sense.

Indeed, where its idealism could be critiqued as perhaps lacking some probing, this is ultimately a message of support to those who need it most. ‘To affirm their lives, and also your own, and perhaps expand your idea of normal’, as Takebayashi puts it. We can sometimes fall into the trap of treating these kids as tragic, when they're just living their lives. Perhaps reminding us of this is all that matters.

Japanese Movie Spotlight is a monthly column highlighting new Japanese cinema releases. You can check out the full archive of the column over on Letterboxd.