Confession time: I didn’t like DEATH STRANDING when it first released. It wasn’t that it was bad, and I had admirable respect for everything it was doing differently in the blockbuster space. I even thought that conceptually a story about how we connect in a fracturing world was a powerful idea. But in a strong year of releases, and with the rough opening hours the game has in introducing us to its cyclical rhythm and ideas, it never worked for me. To be honest, even now, its concept of combat has mixed results and feels mostly unnecessary.

I don’t think I was alone in this either. While the game was relatively well-received critically and commercially, there was certainly discontent and thoughts that perhaps its story felt too far-fetched, its slow plodding through an isolating world not just plain, but not motivated by a sense of reality.

I also wouldn’t be alone in saying that our collective experience of the COVID-19 pandemic and the increasing divisiveness of the world amidst the rise of fascism and fascistic tendencies has only made this game feel prophetic from the lens of 2024. It’s certainly this experience that made me want to return to the game with a fresh perspective, where its meandering, monotone pace of wandering through the world as essentially a postman felt meditative, its story in equal ways prophetic, hopeful… and a warning.

Announced at a recent press conference for DEATH STRANDING 2 held at Tokyo Game Show in September and to mark five years since the game’s initial release, a free exhibit of production assets was held in Shibuya PARCO. In January and February, the exhibit moves southwest, where both the Nagoya and Shinsaibashi PARCO facilities will host these same artifacts of the game’s production. The pop-up museum in the department store's Gallery X may have been small and only existed for a brief 10-day window, but with a pop-up store and several restaurants selling food themed on the game as well, it was a big deal.

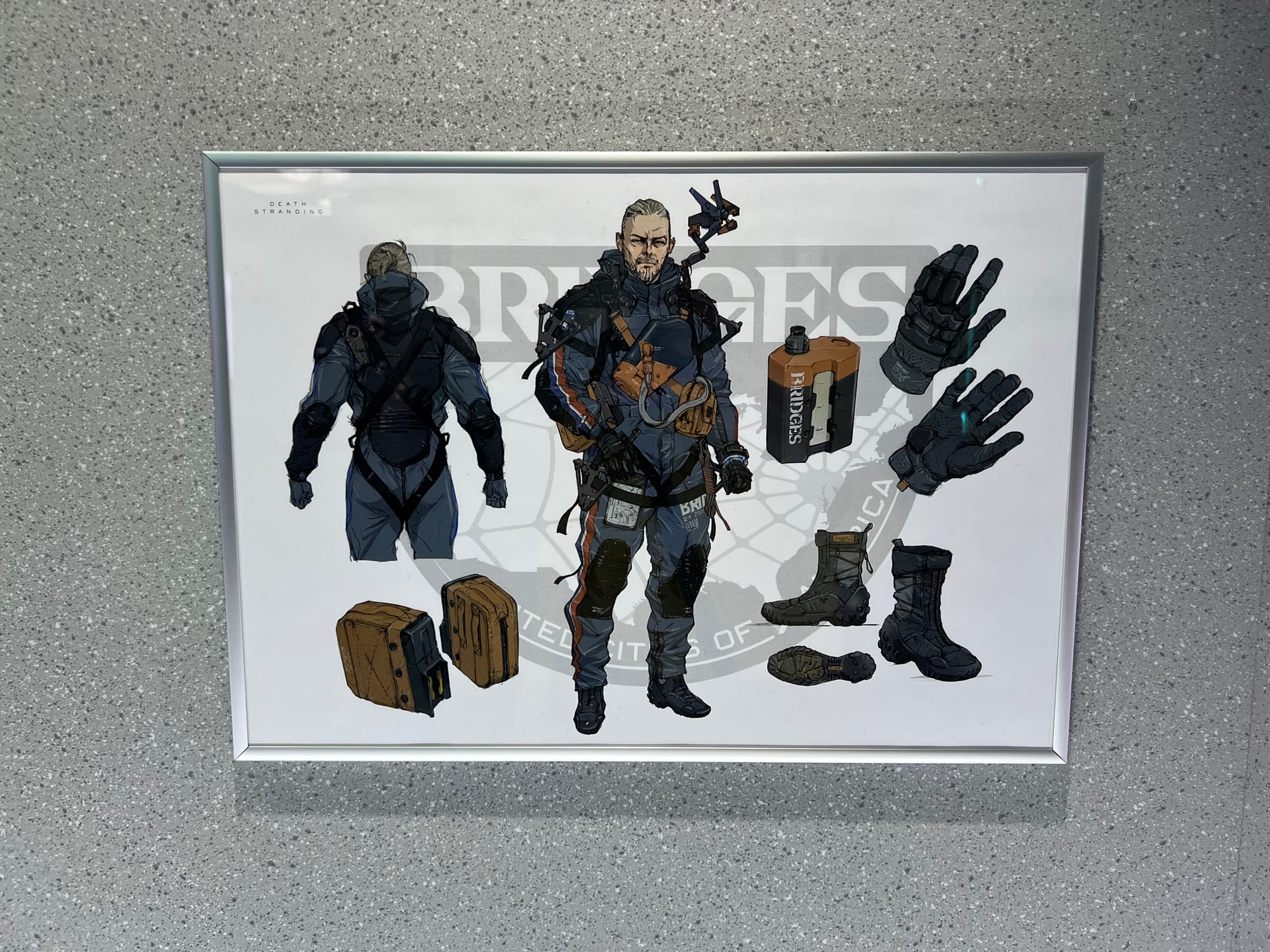

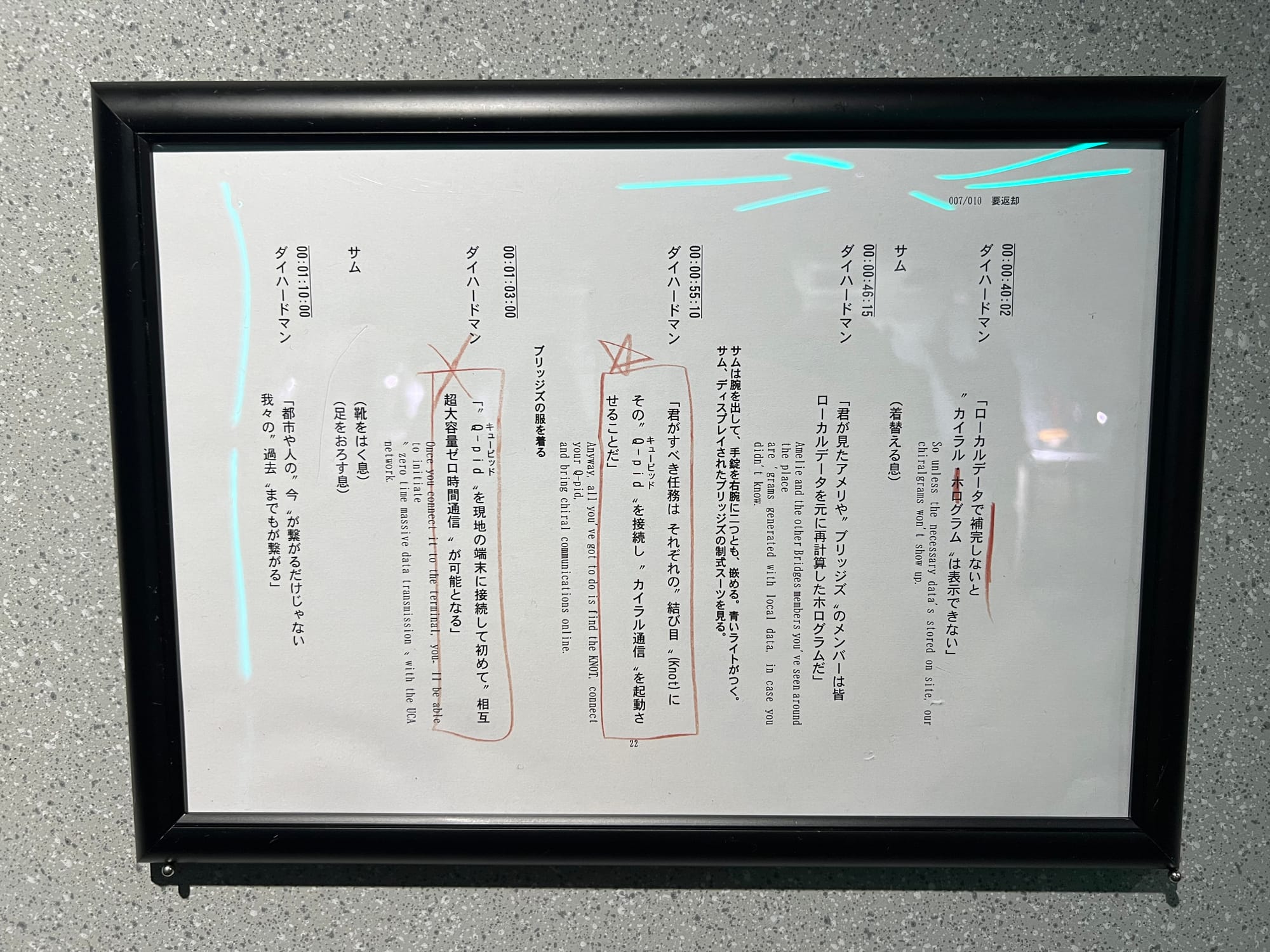

The exhibit was dense with fascinating paraphernalia. Prior to the company having any funding and before any development could be done, pre-visual work was conducted by creating a hand out of wire framing for handprints and using a real baby doll in place of the B.B. you carry to warn against BTs when out in the wilderness. Not only were these here, concept sketches of the main characters by Yoji Shinkawa were on display. On another wall, unfinished development screenshots featured in visual scripts for cutscenes were displayed with dialogue script pages complete with cut dialogue, while the initial pitch document had been declassified to clarify the big-picture ideals of the game.

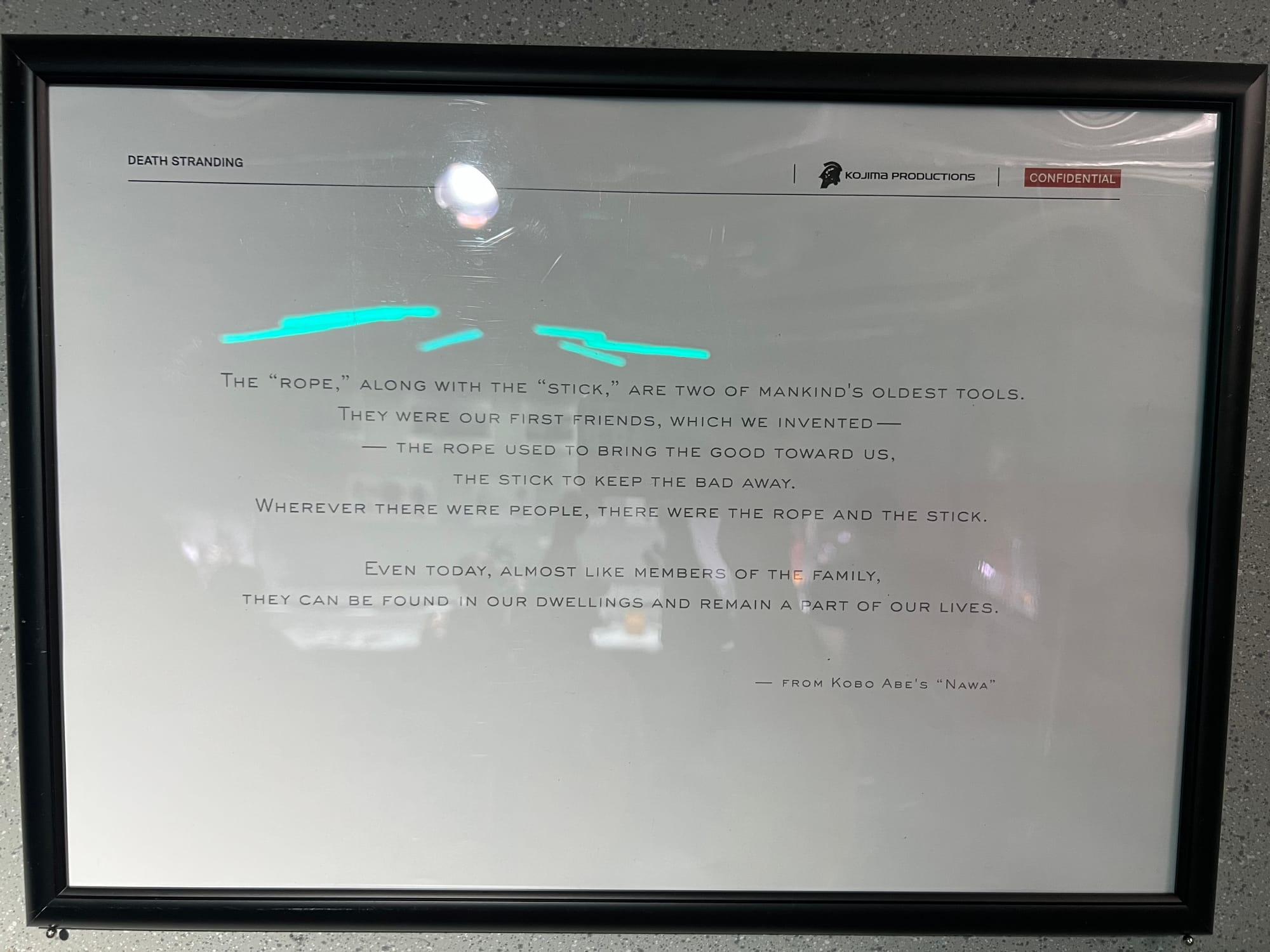

Most notable of all within this initial pitch document was a quote from Kobo Abe, discussing humanity and the concept of the rope and stick. The stick, a weapon of violence. The rope, a tie that binds.

“The rope, along with the stick, are two of mankind’s oldest tools. They were our first friends, which we invented. The rope was used to bring the good toward us, the stick to keep the bad away. Wherever there were people, there were the rope and the stick. Even today, almost like members of the family, they can be found in our dwellings and remain part of our lives.”

DEATH STRANDING was the rope that brings people together, and while it wasn’t that this concept was unclear in my initial attempts with the game, it never resonated. Perhaps from naïveté, the concept of connection told through isolation felt unnecessary.

Yet perhaps it felt unnecessary because, in our hubris, we forgot what it meant to connect. Kojima’s stories, through spy thrillers and war, have always touched on our changing relationships to one another. They’re about betrayal, trust, loss, but only with those we know and were familiar with. We are betrayed by Big Boss in Metal Gear Solid 3, but it’s a story that assumes we are already connected with this person. We never assume that we can be betrayed as a species, because how can we be betrayed by someone we don’t know?

As the throes of a pandemic thrashed against the beaches of the world, distance was enforced, and the solution required us to connect in spite of that. Ever the literal with his names, Sam Bridges connects people even when they’re apart, because there’s no future if we can’t remember and connect with our fellow human even when we’re apart.

But when the connection is lost, it’s so hard to regain that trust. As we siloed online and conspiracies were given space to thrive, this rock-solid grasp on a sense of community was strained. Without the ability to come together, it was lost entirely. And in the subsequent four years, rhetoric grows violent, and an attempt to bridge the gap by understanding and reacting to the suffering that caused this disillusionment in seeing each other as fellow humans has yet to be attempted. Scapegoating is the apparent better solution.

I get it now. Even the combat. As much as I am uncertain if it truly works even still, it means something. It’s not prophetic because it warned of a pandemic or mimicked that reality, but because it proposes a future. As much as people have only become more reticent and glowing of its premonitions, many have yet to grasp the solution it proposed all the way in these initial documents all the way back in 2016.

The exhibition, in the end, served as a reminder of that. And in recognizing the need to take this further as the world continues to fracture, Sam’s newest adventure seems to go further in exploring these many issues. If DEATH STRANDING is only more important in 2024, then its sequel could perhaps be the most important game of 2025.