Rather than a documentary on the state of Ainu people and the challenges of maintaining an enduring culture amidst the colonial backdrop that has defined their life and attempts to suppress it for centuries, AINU PURI is far more anthropological in its approach.

We get context to the state of Ainu aboriginal people in modern Japan through an opening blurb - these native people of Hokkaido were colonized centuries ago and have been trapped between border disputes for Japan and Russia, attempts to assimilate their identity and suppress their culture, alongside discrimination for expressing their Ainu customs, for centuries - but to call this a historical discussion on the state of Ainu life in Japan would be inaccurate. As the blurb fades away, we enter the early morning pre-sunrise, and go fishing.

It’s mundane, ordinary. Shige, a father and Ainu man from Shiranuka, Hokkaido, goes fishing with his son, Motoki. They pray to the gods in hope of good fortune, and thankfully catches a salmon that they take home to eat with the rest of their family, the mother and their baby, that evening. They apologize to the fish for the pain of capturing it before beating it to ensure it is dead, as a way to thank them for their sustenance. Before they eat, they pray once more.

This documentary is not a lecture on Ainu history, the colonialism that threatened to wipe them out, the discrimination faced in Japanese society and an education system that sought to wipe out their language and customs. It’s not that such a discussion is unimportant or is ignored here, or even that a conversation on Ainu culture in conflict with modern Japan is unnecessary. Just this year, one of the larger live-action movie releases of the year, an adaptation of the popular manga Golden Kamuy, faced controversy from some Ainu people and activists for failing to cast Ainu people in such roles, as has been the case throughout the industry for decades. The film did employ some Ainu people to craft the costumes, however.

These are important discussions, but AINU PURI takes a different approach.

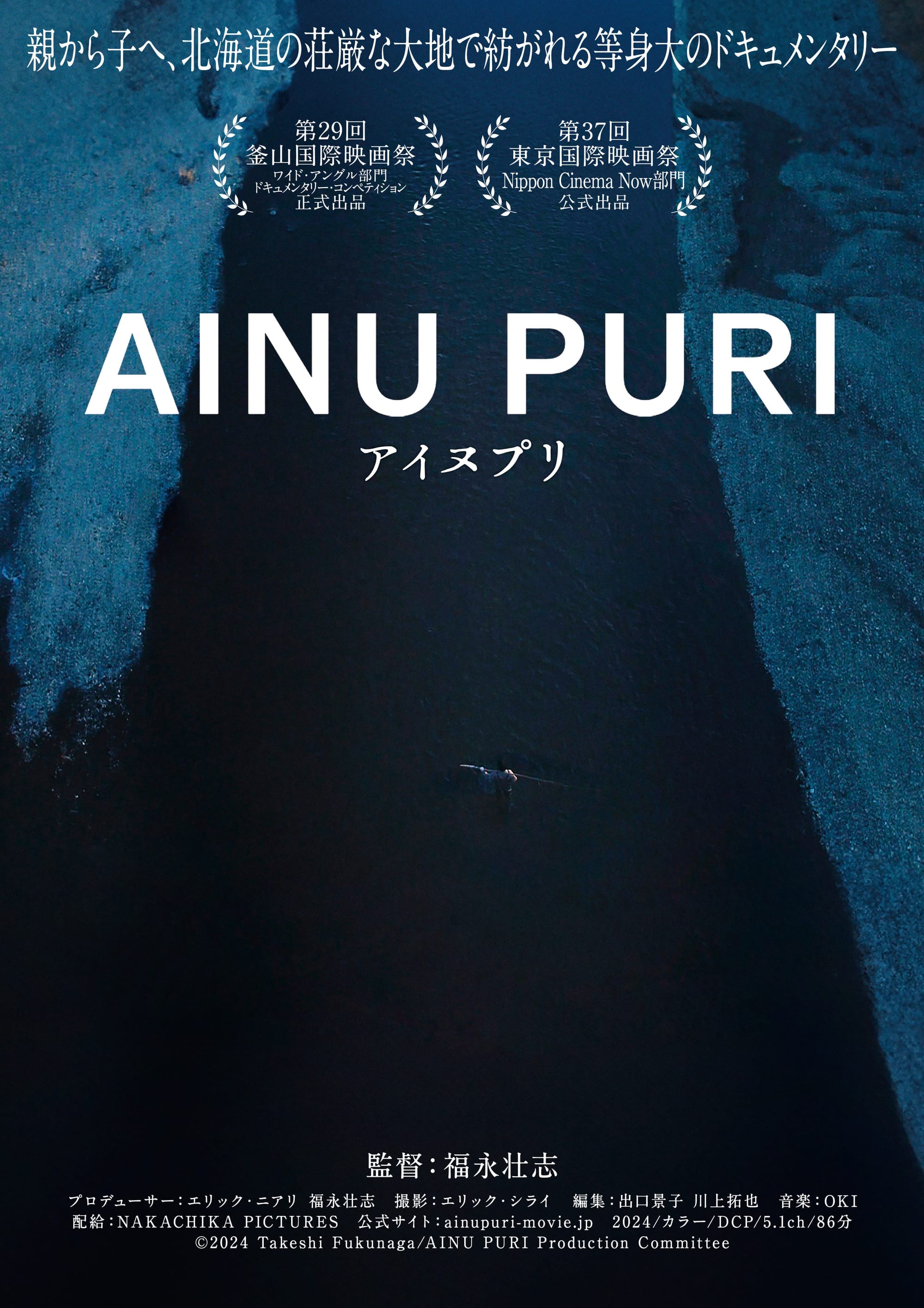

This film, the second by director Takeshi Fukunaga to focus on Ainu people following 2021’s AINU MOSIR and comes after the director’s experience working on the 2022 film Mountain Woman while leading episodes on both Tokyo Vice and Shogun, is more about the communities and people who keep this culture alive than the difficult history that even its subjects at times struggle to discuss.

We exist as a fly on the wall buzzing between two different worlds: the traditional customs of the Ainu, and the Japan that at times is unsure how to discuss and embrace these customs and lives now it’s stopped trying to actively suppress it (but not discriminating against it). In one scene, Shige will perform Ainu rituals with two other Ainu from their small town, Ryutaru and Satoru, and in another they’re working or finding ways to actively commercialize the practices that were once taboo in a way of uplift a group still lacking in wealth in modern Japan.

The suppression and histories that brought us here are discussed, but they’re never the focus. Shige and others in the older generations of Ainu talk about how they were forced to suppress anything that outwardly expressed their Ainu identity, and some would be ostracized for expressing it in school. Ainu people and history were erased, even if that is somewhat changing within schools in the region (the director has admitted that while they’re not Ainu themselves their desire to tell stories like in AINU MOSIR and this documentary comes from knowing Ainu people in his school days and wanting to learn and showcase this more, importantly including Ainu people in those conversations when this is an otherwise rarity).

Japan has historically cracked down on these customs to the point few exist in modern Japan. It’s estimated only 11450 remain in modern Japan, a number that’s halved since 2006 and has been on decline for decades due to their practices being suppressed alongside the practicalities of urbanization and an aging population. The result is that many, including Shige in this documentary, are losing touch with things like their own language. Though Shige is attempting to learn it further and uses the language in prayer, he will even say to the gods that he must revert to Japanese due to his inability to fully express himself in the language.

All before considering the backdrop that modern Ainu representation and existence is still defined less by self-determination and instead by the political institutions forced upon them and the economies of a country that continues to exoticize and ogle without true respect. As AINU MOSIR showed, many face a forced reality of selling their culture to avoid poverty, watering down its intent and assimilating into a capitalist modern society that in the same breath as it feigns a gawking intrigue will deny them representation in stories that discuss their heritage.

These are topics that get brought up in interviews with particularly older Ainu people like Shige and his parents and others within the community. But more than that, and perhaps more welcoming as it allows us to see a side of Ainu life beyond this, our focus is instead on the customs and life and families that continue to exist. The most touching scenes are those where we see Shige teaching his son what he has learned in his own repatriation, or how the entire community comes together to organize some of the dances and ceremonies the people have participated in for centuries.

It puts a face beyond the exoticism often tinging these discussions. We’re simply a part of this group. It’s a delicate balance that Fukunaga has earned the trust to express, capturing the lives of people he spoke to during the production of AINU MOSIR. As we weave between the mature discussions of what it takes to preserve Ainu life in a modern Japan where the colonial history makes modern Ainu culture impossible to untangle from Japanese influence, this is a documentary that succeeds because it’s not trying to solve all of this in the span of 80 minutes.

This is a movie to appreciate the beauty of the Hokkaido landscape and the people who have always been here, captured beautiful by Fukunaga’s small crew and through Erik Shirai’s cinematographic eye for detail and wonder. These people are shown not fighting but thriving, experiencing joy. It could be argued such an approach lacks substance when we spend significant time watching people learn a dance for a ceremony or organize bringing people together than learning the stories behind it, but I found it just as important, understanding much about the importance of these traditions and what they mean.

Most of all, I felt like I knew these people. For many Japanese audiences, even as laws are passed to mixed results to address long-rooted discriminations, don’t know Ainu people, and don’t care when controversies like that of Ainu representation mentioned earlier are discussed. By the end, as we return to the intimacy of father and son that opened the film, they’re a familiar face. It’s warm. We know them now. That’s important. That’s good.