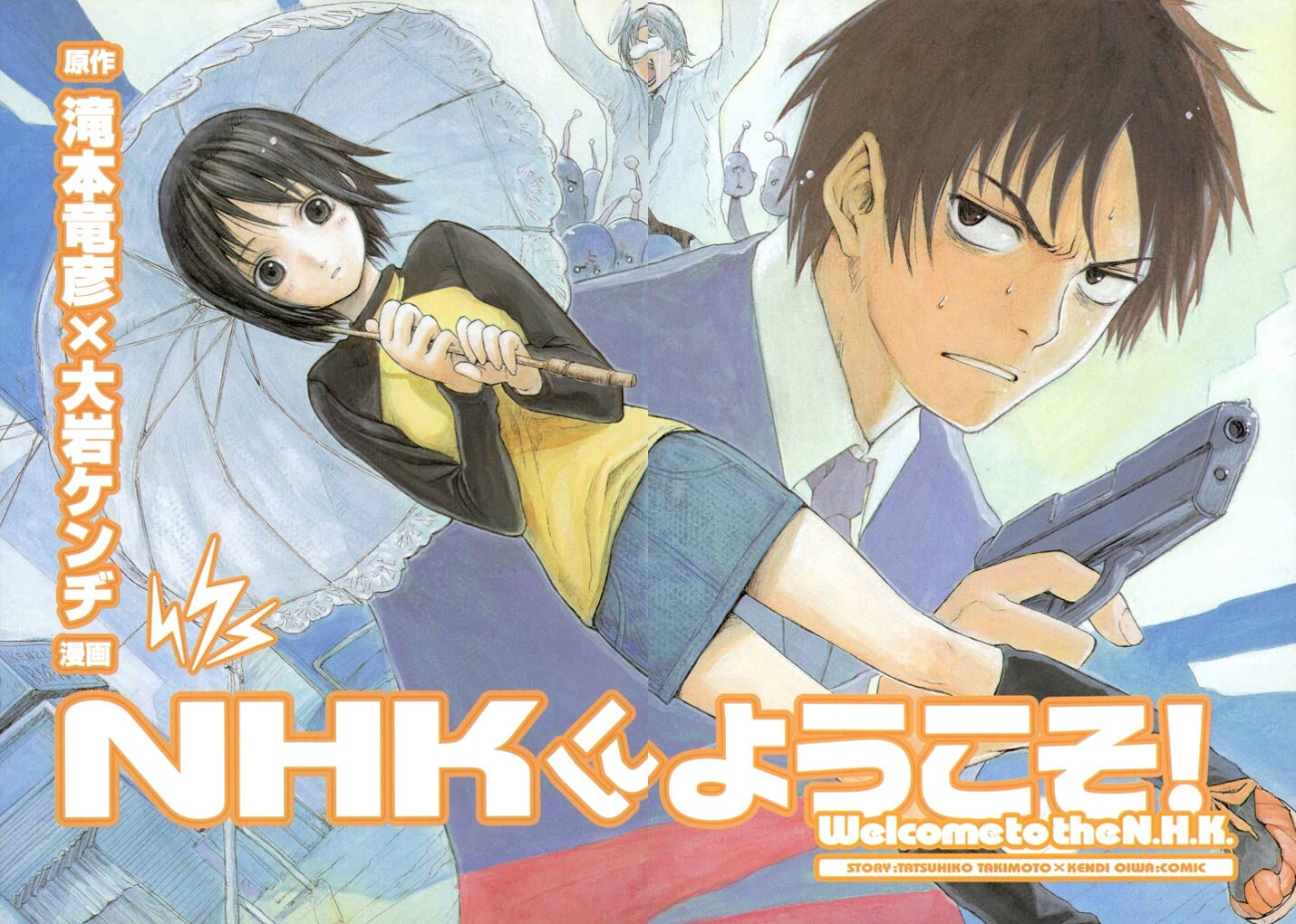

Few light novels have proved as groundbreaking as Welcome to the NHK. Originally published in 2002, Tatsuhiko Takimoto’s seminal work was one of the first pieces of popular fiction to deal with the phenomena of hikikomori shut-ins, only recently codified at the time. It also foreshadowed conversations surrounding otaku culture, lolicon and moe that would come in the following decade, particularly due to Cool Japan.

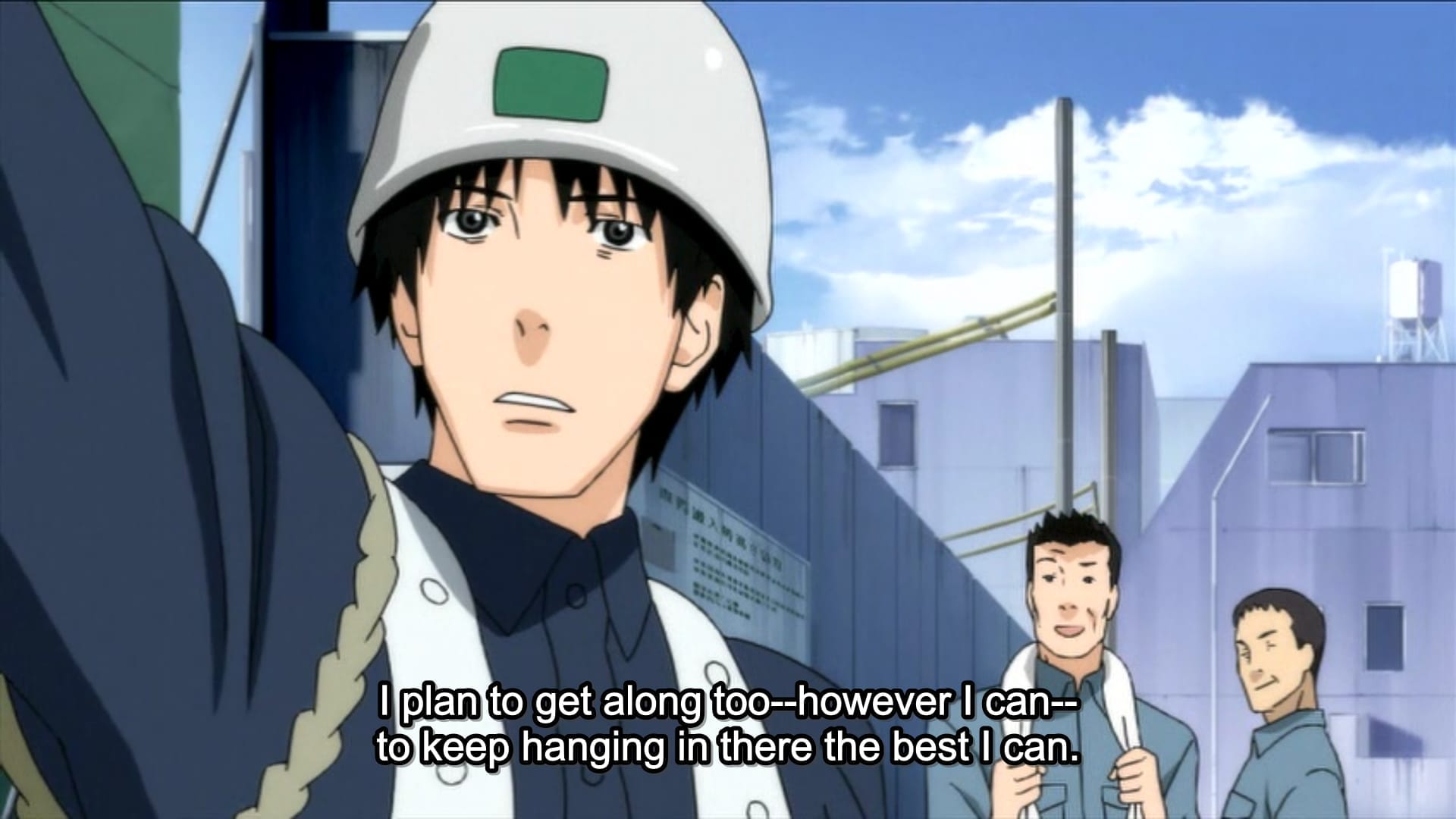

Aside from its cultural significance, Welcome to the NHK still stands up today as an engaging and uplifting story about mental illness and self-improvement. While this is arguably more pronounced in GONZO’s 2006 anime adaptation, it clearly showed that the only way out of depression was to help yourself: no one is going to save you. Many people have taken strength from this, including myself.

With all of this in mind, the idea of a follow-up was always a risky one. In recent years, several major franchises have attempted to rekindle success with reboots and reimaginings, but only a scant few have managed to succeed. Indeed, some have failed so badly that the originals have been ruined in retrospect, meaning that the series’ entire legacy could be on the line.

Luckily, Rebuild of Welcome to the NHK doesn’t meet this fate. While it was never going to replicate the impact of the original, it does succeed in crafting a narrative that’s just as entertaining yet radically different from before. Furthermore, the themes it presents finally provide a solid conclusion that relates to the story behind the story of Tatsuhiko Takimoto.

First of all, it’s important to know that Rebuild of Welcome to the NHK is isn’t really a sequel. The chronology of the series is kept intentionally vague here: there are some elements that imply that it comes after the first novel, but also plenty of contradictions. It’s a neat way of ensuring that this new novel is accessible for new readers, all the while laying the groundwork for the themes that the narrative explores over the course of its run.

Much like the original novel, Satou is a hikikomori shut-in who has dropped out of his second year of college. He receives ‘counselling’ from an enigmatic high school girl called Misaki, makes stupid projects with his neighbor Yamazaki, and counsels his lost love Hitomi through societal ennui. In essence, the basic premise and cast of characters remain the same as before, but the course of the narrative is very different.

What makes up the majority of the novel’s runtime are a series of plot points that initially feel disconnected, but eventually come together in an unexpected way. Misaki gives Satou the chance to earn a “Anything Ticket,” which he plans to use for perverted purposes. Yamazaki ropes Satou into making “adult sleep aid audio” for DLsite, which might help them both with their money problems. Hitomi, meanwhile, finds a way out of her depression by engaging in a mysterious “project” involving an expensive camera and a ring light…

For fear of spoilers, I’ll limit myself to recounting just one particularly memorable moment. After one of his counselling sessions with Misaki, Satou attempts to fix his pornography addiction by abstaining from masturbation for a month, thereby putting himself in the worst frame of mind to find out about the true nature of Hitomi’s project. Spiralling out of control and under the influence of marijuana, he uses VR goggles to try and view as much pornography as possible at the same time, eventually choosing to tap into the multiverse and access his other selves.

While the original novel was celebrated for its portrayal of the fragile mind of a hikikomori, it never featured anything as extreme as this. If anything, one of its defining features was the gritty realism that grounded the setting and allowed readers to empathise with Satou’s feelings of isolation, even if they were fueled by drugs and alcohol. Nevertheless, Takimoto takes a decisively more hyperbolic approach this time, turning the tension and the excitement up to the maximum.

Another key difference comes in how the two stories are constructed. Whereas the original novel was presented as more or less a stream of consciousness from Satou’s point of view, there’s an actual structure to Rebuild of Welcome to the NHK that builds towards a proper conclusion. Each character also has their own part to play, interacting with each other in meaningful ways both through and independently of Satou that gives a real sense of place to the narrative.

Perhaps the biggest departure, however, lies in the central female protagonist. One of the reasons why the characters never really interacted with each other in the original novel was because the story mainly revolved around Satou and Misaki: everyone else was simply there to fill in the gaps. Even so, Misaki takes a back seat this time around after her story was more or less fully explored in the first novel, leaving Hitomi to pick up the slack instead.

As one of the other female characters in the original novel, it always felt like a bit of a shame that Hitomi never got much of the spotlight. Of course, her part was greatly expanded in the anime thanks to the “Suicide Island” arc, but this was an original story not taken from the source material. Indeed, Rebuild of Welcome to the NHK feels like a response to the series’ legacy in many ways, attempting to make up for its deficiencies in a post-adaptation world.

There’s an interesting motif in Rebuild of Welcome to the NHK. At various points throughout the story, Satou remarks that he feels like he’s living in a time loop, repeating the same events over and over. He also mentions memories of events that never happened in the original novel, such as taking photos of elementary school students and going to an abandoned island.

It would be easy to pass this off as something as boorish as a Welcome to the NHK multiverse. While it is true that Satou does claim to tap into such a thing during his marijuana-fuelled VR porn session, he’s far from a reliable narrator. In fact, accepting this would also mean accepting his delusion that the “Japanese Hikikimori Association” or NHK is responsible for his situation, so there’s clearly some deeper meaning here.

During one of her counselling sessions with Satou in the first chapter, Mizuki outlines the theory of “eternal return.” First formulated by the Stoics during classical antiquity, this idea enjoyed a brief resurgence in the 19th century thanks to Sigmund Freud, who posed it as a thought experiment. Among other things, eternal return claims that the universe is periodically destroyed and reborn only to unfold in exactly the same way, presenting a serious challenge to the idea of free will.

Understanding how this relates to something like Rebuild of Welcome to the NHK shouldn’t take much effort. As the follow-up to a novel that uses almost exactly the same premise and same characters again, it feels like the textbook example of eternal return in fiction. Yet, mirroring how the narrative ends up unfolding in a completely different way, Mizuki also outlines the secret to breaking the cycle: to affirm things instead of denying yourself.

In many ways, the story of Welcome to the NHK has always been the story of Tatsuhiko Takimoto. Not only does the protagonist share a striking resemblance to the author in terms of his background and name, the narrative itself was drawn directly from Takimoto’s own experiences as a hikikomori. The initial afterword for the novel reads: "[...]the themes addressed in this story are not things of the past for me but currently active problems."

Hence why it was such a tragedy when the success of Welcome to the NHK drove Takimoto back into old habits. In the second afterword, the author admitted that he had not written anything since the novel’s success and had essentially been “reduced to a NEET” living off royalties. A further blog post came in 2016, where he expressed his frustration that he “could not write what [he] wanted to write” and described being “stuck for years” in an atmosphere of failure and frustration.

Like many authors, Takimoto felt trapped by the expectations born from his own creation. Even so, simply denying the reality that his career was and still is defined by Welcome to the NHK was never going to get him anywhere: much like Satou, he needed to affirm this reality instead of turning away. Perhaps penning a follow-up to his most work was the only way he could finally move on, even if it might seem like something of a cash grab.

On a broader level, the theme of “affirming reality” is an uplifting one that serves to cap the story off in a way that the original failed to do. Speaking personally, I’ve always preferred the anime to the original novel as it provides an actual moral to the series, so it’s great to see that Takimoto was able to replicate this after all these years. Breaking the cycle requires facing reality: that is the first step to reconciliation.

Rebuild of Welcome to the NHK is out now in Japan via Kadokawa.