Hirokazu Kore-eda’s second Netflix drama, Asura, has been a big hit in Japan, even if its global promotion and rollout have failed to bring the deserved attention warranted for such a beloved auteur. Indeed, this series continues the director's interesting career trajectory since earning an Oscar nomination for his work on Shoplifters, a family drama about those often pushed aside or looked away from in Japanese society, a unit stuck in abject poverty relying on shoplifting to survive.

Since 2018 he’s focused on mentoring his protégés, developing movies in France and South Korea, while also creating the superb coming-of-age mystery Monster, using a Rashomon-esque storytelling structure to recall the close friendship and romantic feelings between two young boys, particular one kid whose mother raises concerns about his changing behavior fearing a teacher is physically abusing him.

By comparison, Asura might seem on paper to be an almost-straightforward series for the veteran director. This is a remake of the NHK drama of the same name first broadcast in 1979 and later remade as a movie in 2003 and stage play in 2004. In it, four sisters learn their retired father is having a long-term affair that the wife has seemingly been kept blissfully unaware of, bringing the four together as they hire a private investigator and learn the truth while straining their relationships with each other and the people they love.

This fascination with the dynamics of the family is a theme Kore-eda has stubbornly returned to time and time again over the decades, including in his afore-mentioned Oscar-nominated great and many other stories. This even includes another film in which he has focused on this feminine, sisterly dynamic amidst adversity, Our Little Sister. That's not to say you've seen it all before when it comes to the way Asura plays out.

A rote-standard portrayal of family amidst adversity would likely not remain in the public consciousness for this long were it not to hide some additional layer underneath its surface, nor would it likely attract such an accomplished director to lead production in a modern take on this story. These layers are apparent early on in the ways these young women lash out at the camera through the film’s opening credits, or the complex ruminations on cheating and family that stand as radical even within Japanese society today, never mind when the series first aired or its now-period setting. And it only gets more intriguing from there as it slowly unravels itself.

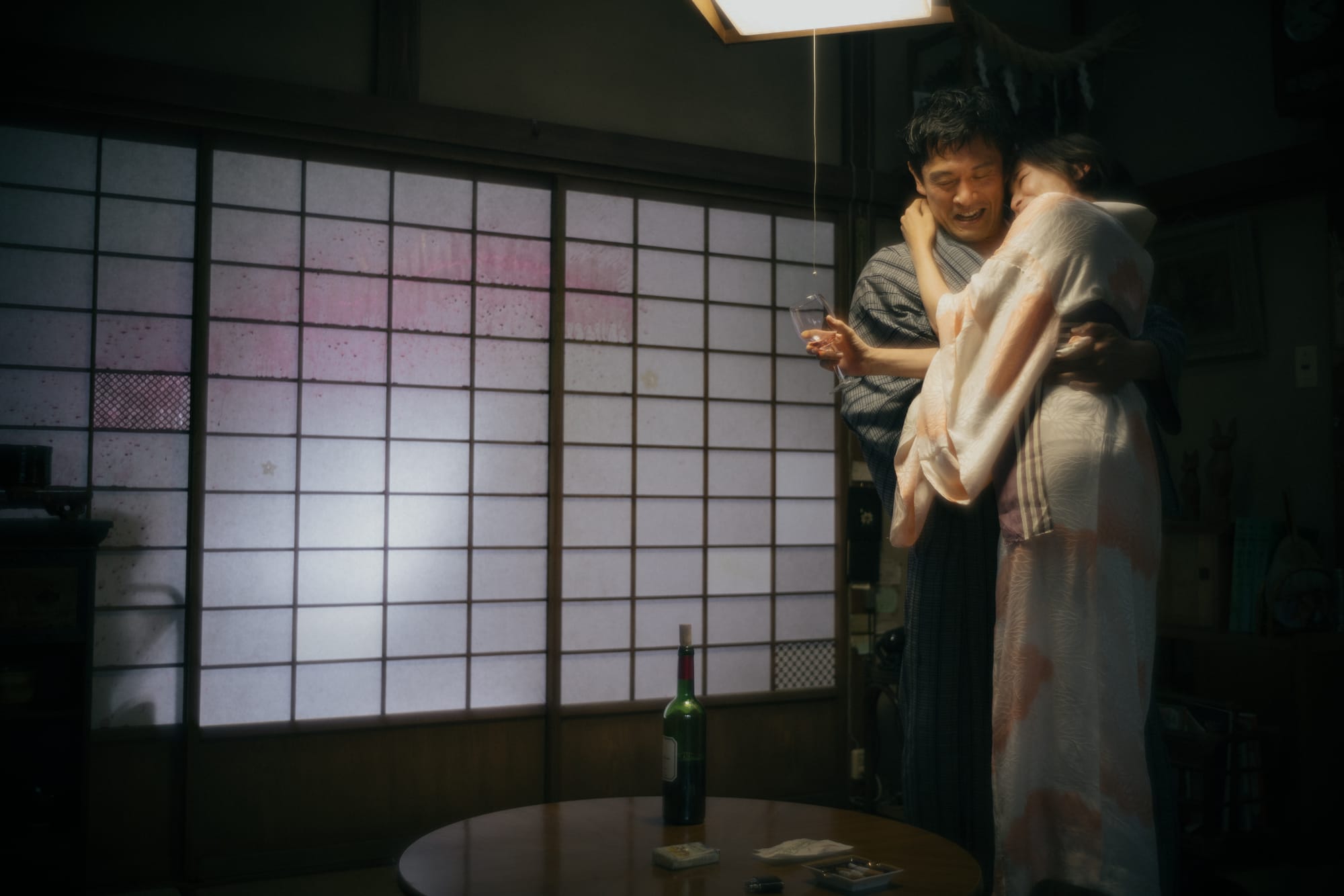

Kotaro, the adultering older father in question, leaves his home twice weekly under the guise of work to meet another woman. Takiko (Yu Aoi) reveals this truth to the others sisters having received the results of a private investigator’s search into the affair, inevitably leading to the question of whether to tell the mother, risking their happy life and blissful ignorance, becoming a heated topic of conversation. This point it’s gone on for years, and if they’re still together and have each other, is the risk of a breakdown of the marriage, leaving them both alone without the other’s company in old age, one worth taking? You can’t put that secret back in the bottle once it’s out in the world.

Never mind that one sister, Tsunako (Rie Miyazawa), is having an affair with her married boss, Makiko (Machiko Ono) thinks her own husband is having an affair, and Sakiko (Suzu Hirose) is otherwise not on board with telling the truth.

In 1970s Japan, views on such acts weren’t exactly condoned, but also didn’t incite the same reactionary calls of immorality that they would elsewhere. In a patriarchal society where the head of the house could be the sole breadwinner, the allowance for fun and to blow off steam amidst this responsibility is something some would turn a blind eye towards if handled with secrecy and decorum. The power dynamics that could keep one in an unloved marriage and away from independence didn’t give much chance to complain if they knew the truth, anyhow. So it’s dismissed. He’s just a guy, it’s fine, they say.

Even if society, while still unequal, is far improved from the gender imbalances of the 70s, their stories resonate as the core of these issues remains unchanged. This is what allows Asura to soar in a modern context under the retro bloom and warm colors of Showa Japan. If anything a modern perspective on this era and story coupled with the introspective lens Kore-eda points at our four sisters only highlights how little has really changed. For all we can see how the fashion and streets have changed, the minds have not.

To simplify the story even to this would not give Asura justice. As events unravel and the family is strained even beyond the question of faith in marriage, what follows is a thorough dismantlement of the barriers that influence this line of thinking and emboldenment till the pent-up frustrations are unleashed on themselves, each other, and the world around them. It doesn’t change things, nor should you expect it. But they unleash their frustrations and disavow the society’s expectations for their own self-preservations and joys.

To impress the story and bring its ideas and this fired-up message of balance in living for yourself within society to a modern audience, to open that up for the audience to take into their own lives, is a far greater endorsement of how this show attacks the true pain at the core of the series. To live without ensuring you take a role in protecting your independence and honor, especially as a woman where that injustice is warped into an expectation, is worth causing a storm.

This is all held together by the quartet of female performances that give this story momentum (although it would be remiss to ignore Keiko Matsuzaka’s performance as the conflicted mother of these four girls, Fuji). In particular, Makiko’s outer strength and inner vulnerability made visible when out of sight are portrayed with equal vigor in a way that steals just about every scene she is a part of. Of all the women, it is perhaps her that has it most rough, and her struggle to hold it together is in equal parts heartbreaking and infuriating and moving.

Combined, Asura has already cemented its place as a series we will likely discuss at the end of the year as being one of the best. It’s hard to imagine few, if any, surpassing the emotion and beauty amidst adversity on screen here.

More importantly, considering the series’ success in Japan amidst a backdrop where the same issues of a women’s ability to assert herself are of major debate, whether it be in the choice of surname or in the workforce as pushes to greater equalize the gender gap stall. Would I say this is a radical piece of media? Not at all. But through the sheer power of its acting, story and message, it speaks to a particular core that screams for assertion as the way to be heard. Asura uses the past as a mirror of the present, repackaging a familiar and beloved story in a modern sheen that asserts its never-ending relevance and timeless themes.

It’ll warm you, it’ll hurt you, and it’ll make you see the world a little differently as the credits of its final episode roll. That is the justification for this remake to exist.