In the pre-opening Nintendo Direct for the museum, Shigeru Miyamoto introduced the Nintendo Museum by saying that it is a “place where you can learn about [Nintendo’s] commitment to crafting experiences that value play and creativity”. On the museum’s website, they note that the museum is a place where “you don't need any special knowledge or familiarity with video games to make the most of your visit”. If this is the intent, then the Nintendo Museum is a failure.

In 1969, Nintendo opened a construction plant in the town of Uji in Kyoto. While the company was founded on the production of hanafuda and playing cards in 1889 and continued to grow through a unique history of toy manufacturing, the late 1960s into the 1970s saw the company struggling to turn a profit. So, they diversified. They ran taxis while making instant food, copy machines, storage solutions, much of which was produced here.

Then they released the Beam Gun, a light gun toy that would become a massive hit and sell over 1 million units. Then they moved into electronics. Then they made gaming devices like the TV Game, Game and Watch and the Famicom. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s responsibilities were shifted to a larger factory elsewhere in Uji, until it took a customer service role and later shut down.

They built the museum on these grounds. Although there is a tiny notice on the second floor briefly discussing the history of the building, it’s a richness of history right under the feet of attendees that is otherwise entirely overlooked by the museum. Despite having the opportunity to explore and elevate this history, it doesn’t. This sets the tone for much of the experience.

Making my way through the security gates at the entrance of the Nintendo Museum, I entered a large courtyard. Retaining the layout of the old factory, at every turn you’re bombarded with brand recognition. Glance to the roof of the building and you’ll see a Mario checkpoint flag, or maybe even a blue Pikmin chilling on a rock. Lockers and umbrella holders are Game Boy references, there's a Kirby vending machine, a Pokemon manhole cover (the latest in a nationwide initiative). Enter the front doors and you can meet some singing Toads. Before receiving an explainer from museum staff about the rules of the museum, there’s a large mural featuring Nintendo characters throughout the ages from Splatoon to Mario to Band Brothers.

The museum itself is split into two floors. The first floor consists of an array of interactive exhibits based on Nintendo history that attendees can play using the limited number of play coins included with your admission. Ten coins are granted to a special entry IC card provided at the entrance of the museum to use in order to participate in these games. This limit also makes it impossible to play all the experiences in one visit.

Although initially frustrating knowing that you won’t be able to play every game the museum has to offer, this is surprisingly less of an issue by the time you’re there. Between lines of 20-30 minutes for more popular exhibits and other activities, it’s surprisingly difficult to spend all your coins. Having arrived at 1pm and staying until closing time at 6pm, I ran out of time before I was able to use all 10 coins during my visit.

These games are fun, unique, bespoke experiences. Zapper and Scope SP is a game using upgraded NES Zappers and Super Scopes for a large shooting gallery featuring Mario characters on a large screen with up to 12 other players. The sensor was reliable enough that you could even shoot enemies on one side of the screen while standing at the other, and it was a lot of fun to compete with others. There’s experiences that let users play with replicas of the Ultra Hand and Ultra Machine toys from the pre-gaming days, the latter taking place in ‘batting cages’ designed to look like 1960s Japanese households that saw you hit the table tennis-like balls against retro phones and TVs.

However, it was the big controller games that were undoubtedly the biggest attraction. Giant replicas of Famicom, Super Famicom, Nintendo 64 and Wii Remote controllers were built for two players to either co-operate and compete on various challenges. Using the giant Nintendo 64 controller you could take on challenges in Super Mario 64, or you could fly a plane in a special version of Wii Sports Resort.

As cool as this is, it highlighted how surprisingly ill-considered aspects of the museum were. On the one hand, no detail had been spared in crafting these large plastic models for the controllers. In the Wii games, a special HD remaster of Wii Sports Resort and Wii Party (the two games available in individual Wii Remote Big Controller exhibits) had been produced, new UI being produced to seemlessly introduce instructions on using this different control scheme into the game itself.

On the other, no system was in place to support attendees visiting alone who wanted to take part. You need a second player, and staff won’t step in if you’re a solo player to ensure you can take part. Attending alone while on a separate trip to Kyoto for my own interest and to cover the museum for this article, I was almost barred from the experience till another guest in the same predicament happened to ask the question just minutes later while I was still in the vicinity.

Had that not occurred, I simply would have been unable to participate in one of the biggest attractions of the museum. Never mind how demeaning it felt to be pushed away and unwelcome to the point I wanted to leave there and then.

On the second floor was the ‘main event’, although this exhibit somewhat stretches the definition of a museum. This non-linear consummation of Nintendo history featured large double-sided glass panels dedicated to each gaming console, although these are more product showcases than anything resembling historical insight. There’s no written blurb to inform or discuss the state of the industry at the time of the console’s release, why Nintendo chose to develop the console they did at this time. No use of the vast internal documents the company has in their archives to provide context and history of one of the most influential companies in the industry.

On one side of the glass panel, well-preserved boxes of Nintendo-published titles from each region are on display, with a separate area for regional exclusives and a small notice of their release dates. On the other, a description of the console’s features alongside core third-party titles available on the system. For the Nintendo DS, for example, this includes notes about the launch of Touch Generations or the use of the microphone, featuring examples of games embodying these trends like Nintendogs.

It can be neat to see games you remember, but the novelty soon wears. There’s no history here. For a company built on fun these displays felt sterile, and easily could’ve been ripped from a corporate powerpoint and placed inside a glass case as-is. Without discussing their impact, they felt meaningless. A good museum can take something you know and bring new perspectives and knowledge, using it to tell a story. This lacked that.

Unlike what the website claims, non-gaming fans will feel completely clueless looking at these exhibits. What’s the importance of seeing a box of Captain Rainbow on Wii? Never mind that this format makes looking at the Nintendo Switch area of the display feel no different than wandering into an electronics store, especially since some games here and elsewhere were missing and replaced with low-effort washed-out paper cutouts.

Exhibits on Nintendo’s pre-gaming history did far more to elicit excitement as it felt a greater effort was made to chronicle and inform on obscure history. A ‘history of play’ tracked 1890s hanafuda cards through the hugely-successful Disney toy collaborations of the 1940s, toys like the Ultra Hand and Ultra Machine and beyond. While these are well-known parts of Nintendo history, many others on display were not: Captain Ultra Toys or those based on kaiju characters I hadn’t heard of, and some were simply bizarre like the Hip Flip (worn at the waist with a pole connecting two people, you move your body in order to turn an arm in the center).

On screens above these displays, trailers found in the Nintendo archives were restored from original tapes and film reels. Across multiple displays storing tons of toys from over the years in great condition, about 20-30 minutes of old commercials showcased the evolution of Nintendo toys and Japanese domestic life for 100 years.

Greater written context would have been appreciated, but unlike other areas of the museum it felt like attempts were made to tell a history, and you could at least contextually glean an insight into a changing Japanese society through the products of each era. You could see interests evolved through toys, and how this made the company’s move into gaming feel far more natural. Yet even this lacked context: we see Nintendo’s practical items like copy machines as its toy business struggled, but no context, with some initiatives like the aforementioned taxis completely ignored. Hardly a history of Nintendo here.

Whether gaming or otherwise, this was a common theme, and disappointing considering Nintendo is one of the few that can achieve this by having access to the materials. Various independent gaming museums do so much to preserve not just games but the media around them, the prototypes, and contextualize it. I wanted more of that existed here. In one small corner, this wish is rewarded: prototype controllers like the fabled Nintendo Star controller prototype for the Wii was given its first public appearance in a brief peek behind the development curtain.

A timeline of Wii Balance Board development was on display here, starting from a single-sensor wood-and-metal square to something more practical and resembling its final design. Ultra 64 controller molds. A Game Boy Micro more reminiscent of a Nokia 3310 in size and shape than the final design. A Nintendo DS that opened like a book. A GameCube controller shaped like a boomerang with an analogue stick on one side and its kidney-shaped X and Y buttons replaced by a yellow circle of buttons around a larger central button.

This was such a fascinating display that I stood in awe, but as I said before, without context these are confusing oddities and lacking the context to truly appreciate what makes them special. Even being in the know, why these designs? Why divert from these ideas to the final product we have today?

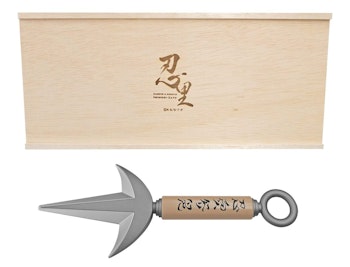

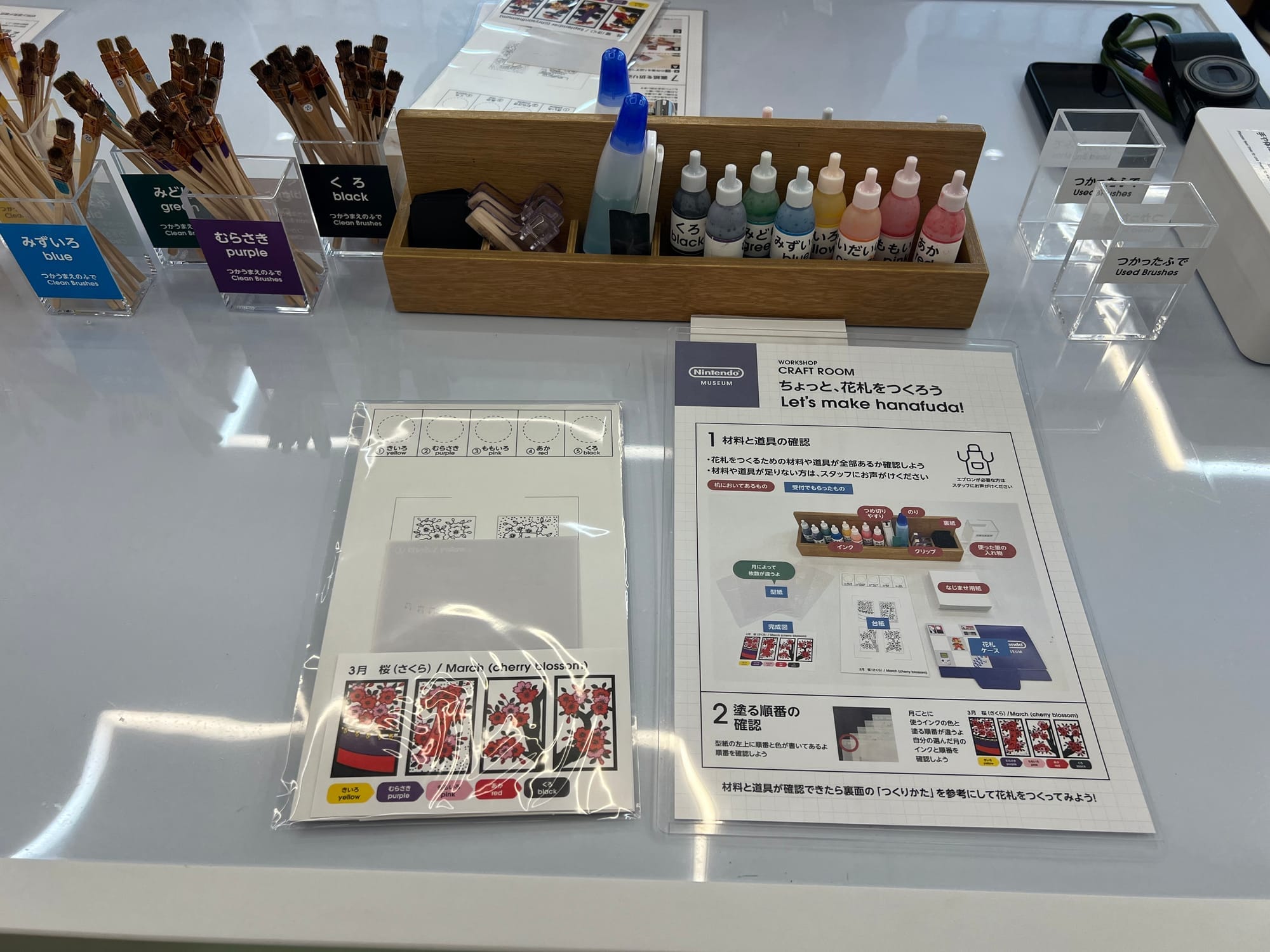

The non-linear nature of the museum works against it, failing to tell a history beyond a disconnected array of non-contextual corporate adverts propped by in-jokes of Pikmin carrying Wii remotes that make it more easter egg hunt than museum. This isn’t cheap, either. At 3300yen for an adult and 1100-2200yen for children, a family could easily spend over 10,000yen before entering the door. This is before paying extra for workshops. I paid 2000yen to make Hanafuda, and while I had a lot of fun crafting Hanafuda cards from scratch and felt it was worth the price to craft cards using paint and stencils, it is an additional expense.

The restaurant is also pricy. While you wouldn’t expect the visually-ornate foods of Universal Studios’ Nintendo World in a museum, it doesn’t provide a flattering comparison to Hatena Burger's McDonalds-like burgers that will somehow cost 2000yen in the on-site restaurant.

Many public museums are cheap or free to enter in Japan, and even private ones will have more extensive displays for half the price or less. In terms of what is available at the museum and its attachment to pop culture IP, the closest comparison would be to the Ghibli Museum. Yet the latter offers a greater context and look behind the curtain, is far cheaper, and has exclusive short films and rotating yearly exhibits. After attending once, there’s little reason to return here unless Nintendo introduce a similar rotating exhibition, new interactive, and bring more archival history out of storage. Considering photos in prohibited areas like the prototypes are already online from some guests unable to follow instructions, this seems unlikely.

It feels like a wasted opportunity. I doubt few expected a notoriously-secretive company like Nintendo to rip open the doors to their deepest secrets, but this just isn’t a museum. It’s less about history but your own connection to this history, which may work for some but feels like a dereliction of duty to a medium that has such cultural impact yet has often disregarded or actively fought against attempts to archive its history.

There is history here. On the floor beneath your feet, in the rare points that the company indulges in the past. A calligraphy mural painted by Chinseki Tsumura featuring the first two characters of the company’s name to represent the phrase ‘leave luck to heaven’ and has proper written context. In the Hatena Burger, I overheard some business guests guided by an employee told how the palettes and plastic boxes used as seating are actual pieces from the factory floor during its operation. But it’s rare, often unlabeled. Seeing more discussion online about the Animal Crossing-like present box hidden inside the restaurant than things you can actually learn inside the museum feels telling.

At the end of it all, that's not entirely a bad thing. At one point, I heard a dad in his late 30s or 40s so excited to see footage of Pokemon Stadium play on a screen in the Nintendo 64 area that he gushed about the nostalgia and memories he had playing the game on its release. The kid, in turn, shared stories of playing modern Pokemon games with their friends.

I don’t want to deny that joy from people. Nostalgia isn’t necessarily a bad thing. I write about this experience leaning on a large Wii Remote cushion purchased at the museum. But alone, it doesn’t enrich, it doesn’t inform. Nostalgia, by definition, is a simplification of the past that defies deeper understanding for rose-tinted glasses. That feels like a disservice of the effort it takes to attend, and how worthy this history is of being discussed with maturity, not pandering.

What’s the point of a museum if you don’t want to share your history?