In The Art of Makoto Shinkai: A Sky Longing for Memories, the book notes how production on The Place Promised in Our Early Days began with Makoto Shinkai to continue the work he undertook in his mostly solo productions like Voices of a Distant Star by handling all the backgrounds of the film himself. It didn’t take long before the realities of Shinkai’s first commercial animation feature project ran against the director’s ideals, but even when he further delegated this work, many of those brought into the project were, like him, not from traditional animation production. Many were art school graduates.

If the awkward delegation of the artwork for the backgrounds was anything to go by, this was going to be a transitional movie for Makoto Shinkai. Still inexperienced in the anime industry and not even touching 30 by the time he was put in charge of his own team for his debut feature, every open door brought with it the pitfalls of responsibility, and the hubris that repeating everything on a larger scale will get the same results would need to be challenged by a new approach, as seen with the backgrounds. Taking unique solutions to these problems, like hiring non-anime artists, would come to define Shinkai’s style going forwards.

The Place Promised in Our Early Days is an odd movie from a conceptual standpoint and as a feature within the director’s career, with its visuals and story standing apart from what came before it (or since). With an open-ended story filled with gray actions, dreams, regrets, and a necessity to mature and face the past to progress into the future, driven both by nostalgia and possibility, this is a movie particularly worth revisiting in a post-Your Name and post-Weathering With You world.

Unlike Anything Else

One of the first things standing this movie apart from those which followed is its setting. Far from the modern Japanese backdrop of 5 Centimeters Per Second onwards, this has far more in common with his similarly underappreciated short film Voices of a Distant Star through its alternative-reality sci-fi-inspired setting and high concepts.

Mixing these sci-fi topics with a fictionalized take on the what-if scenario through which Japan could have been divided after World War II by the USSR, The Place Promised in Our Early Days takes place in a world where separation in 1945 birthed two nations: Japan, and Ezo, controlled by the Union and encompassing Hokkaido. In Ezo is an impossibly tall tower stretching above the clouds, and two boys named Takuya and Hiroki are working on a plane that can cross the secure border and allow them to see this tower up close.

Of course, things aren’t that simple. Both have a crush on a young girl named Sayuri who ends up hanging around with them as they build this plane in an abandoned factory one summer, working with a man with questionable ties to groups with ‘something to say’ about the separation of the country. It also doesn’t help that no-one knows what this impossibly tall tower is for, except that for all people in the mainland have been able to use parallel universes to replace matter no larger than a grain of sand, they’ve replaced miles of land in a radius around this monolithic structure.

And if that wasn’t enough, Sayuri seems to have ties in her dreams to the tower and these universes.

On the one hand, this movie is a fascinating sci-fi story that engages in the same themes of love defined by impossible distances and the way our connections to one another can be built and lost: themes that have defined much of Makoto Shinkai’s career. But to simplify it to this when the story touches on so much more, from nostalgia to youth to the politics of the Cold War and the inability to see an enemy as a person (notably we never see the face of someone from Ezo), as well as the vast potential that technology has to harm and help humanity, feels counterproductive.

On the other is a visual and thematic bridge that unlocks a key to understanding how Shinkai has grown to develop the ideas he returns to in each new film he pens and produces.

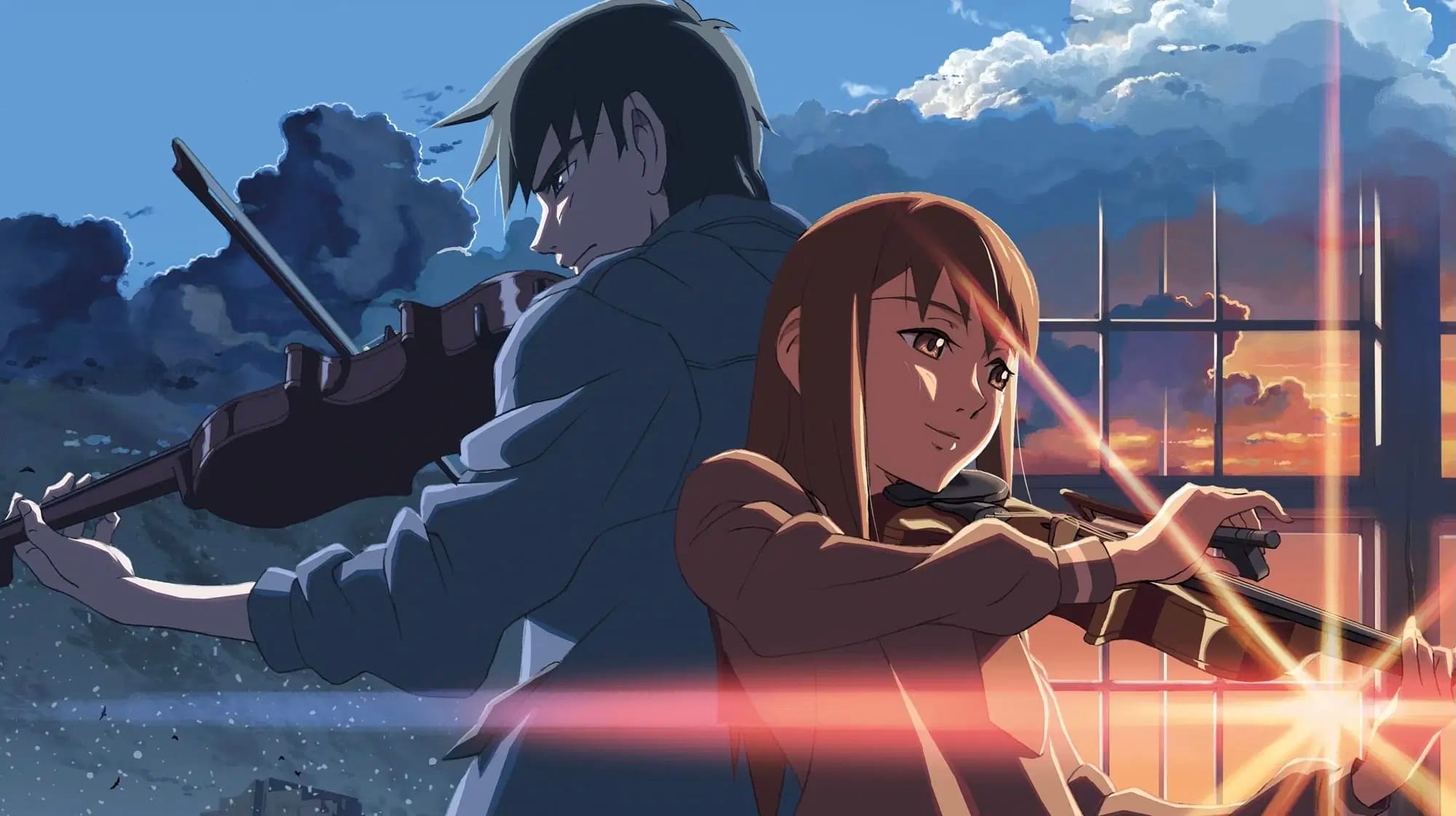

From a visual standpoint, The Place Promised in Our Early Days is familiar yet distinct. The realistic style that Shinkai has achieved using a blend of photography and animation (a style that has recently been adopted by numerous creators in the wake of his success) has a place here, but the results are far more painterly and sketchlike than the photorealism of what followed after 5 Centimeters Per Second. This carries across to the characters, whose designs are far rougher than what we may be used to today. Outlines are loose, flowing through the screen like the noise emanating from Sayuri’s violin that similarly serves a strong instrumental theme often overlooked for pop hits in recent work.

Considering the first part of the movie plays towards an unforgettable summer for our three protagonists, indulging in a hopeful yet seemingly impossible dream and a promise that can’t be kept, only to have the second half of the film feature our characters driven by regret and grief of what they lost, this almost-nostalgic look enhances the story being told. The sketches give off an air of uncertainty that matches the haziness of recollection and memory, and it should be also noted that the deep reds and rays of a deep sunset are exaggerated as it glows through the translucent panes on the abandoned plane hangar. A first romance, idle conversation, and playful banter are unimportant to memories of this fleeting time in their lives that are looked back on with regret for what could have been.

In the unstable future, the cooler colors deepen our distrust of the modern world and the loss of direction as the connections they once had are lost. Yet each time, its imperfections are simply exaggerations of an indescribable longing that ties to this initial nostalgia.

Then we have the story, distinct from anything that followed it. With the bonds between our characters being thrown apart by the uncontrollable war playing in political offices and spaces beyond their comprehension, it feels like a mirror of the story of Mikako and Noboru in Voices of a Distant Star, whose story saw them torn apart by Mikako’s involuntary recruitment into a war in space where they can only communicate by texts as distance turns their delivery from minutes into years.

While aliens and space are out of the picture here, the distance between these characters is no doubt exaggerated by the war and Sayuri’s connection to the tower pulling her away from Takuya and Hiroki, with the grief from her disappearance equally tearing them apart. And this is a war as unexplained and mysterious at the start of the movie as it is at the end. Yet there is intrigue in how these ideas are portrayed and an acceptance of the potential that learning of ideas beyond our own could still bring people together, even if they can just as easily do the opposite. It feels somewhat prophetic when today, new discoveries bring distrust alongside the potential they bring for change.

The Place Promised in Our Early Days ruminates on these new ideas and heady concepts while grounding itself on a human story of nostalgia, broken promises, regret and love across a divide that can’t be breached. And even if these ideas have been ones Shinkai has explored in the years since this film’s 2004 release, where this ultimately stands apart is in its approach.

Through its sci-fi theming on a feature-length scale, and its nostalgic imagery and visual style, The Place Promised in Our Early Days occupies a place in Shinkai’s career he appears unlikely to revisit. Yet maybe that’s not a bad thing. In how the film lingers on its moments of serenity and looks back on good times which reclaiming leaves only ambiguous claims that it brought any overall remedy for their years of regret, this feels like an attempt by Shinkai to close the book on his early career and embrace his role as an anime director, whether that be through establishing a thematic idea in the film itself he would return to in later movies or delegating backgrounds to other artists to take advantage of the talent willing to support his vision.

It may not be perfect, but this movie’s approach to sci-fi romance feels just as fresh today as it did in 2004, and that alone is worth revisiting.

This piece was originally published to OTAQUEST on July 19, 2021