Movie pamphlets are a unique part of Japanese movie culture, and an endearing aspect of the experience in the country. Almost like going to the theater for the latest musical or play, it’s possible to buy pamphlets filled with cast profiles, interviews and more on the latest films. They can range in quality, as with anything, but they have the power to enrich the experience of seeing a movie beyond that of seeing the same film in another country.

The theatrical comparison is no coincidence. The origin of the pamphlet to Japanese cinemas mirrors the growth of cinema from theater, and in pre-war early-1900s moviegoing culture would serve as small leaflets given for free by theaters to introduce the movie and advertise the next week’s programming. While early cinema around the world was presented as a more theatrical experience than it is today, this was taken a step further with the introduction of cinema to Japan with pamphlets being just one part of it which endures today.

Early cinema in Japan could be viewed as a mixed-media blend of cinema and theater. In countries like the US, silent movies would be accompanied with live piano, a practice that only disappeared after the introduction of the talkies with the 1927 release of The Jazz Singer, making live musical accompaniment obsolete. In Japan, movies would be screened with benshi, performers who not only played music but would provide live commentary on cultural aspects for international films, or bring dialogue to silent films by playing the characters.

These performers would gain a following as actors to the point audiences would attend movies at select theaters based on benshi. Such jokes and commentary meant the same film could produce entirely different experiences on a per-theater basis. It’s a theatricality that helped silent films endure, as benshi and silent films continued to command audiences long into the 1940s. A translation of other theatrical practices like pamphlets would become commonplace in the Japanese moviegoing experience to introduce the medium to the masses as something equivalent to a trip to the theater.

Only in the 1940s did free pamphlets fall out of favor as paper went in short supply due to Japanese involvement in war. Paid pamphlets were introduced instead, a practice that led to more pamphlets being tailored to a film rather than as advertising for other films, an evolution that makes them the souvenir of a film we see today.

Even as the popularity of benshi fell away and the movie experience continued to change, pamphlets endured. Almost every theatrical release now offers a pamphlet for sale in the theater. Some are formulaic and minimal, introducing cast, crew and story with minimal interviews, while others seek to deepen understanding of a work through essays and a behind-the-scenes look that celebrates their meaning and the work of those bringing these films to life.

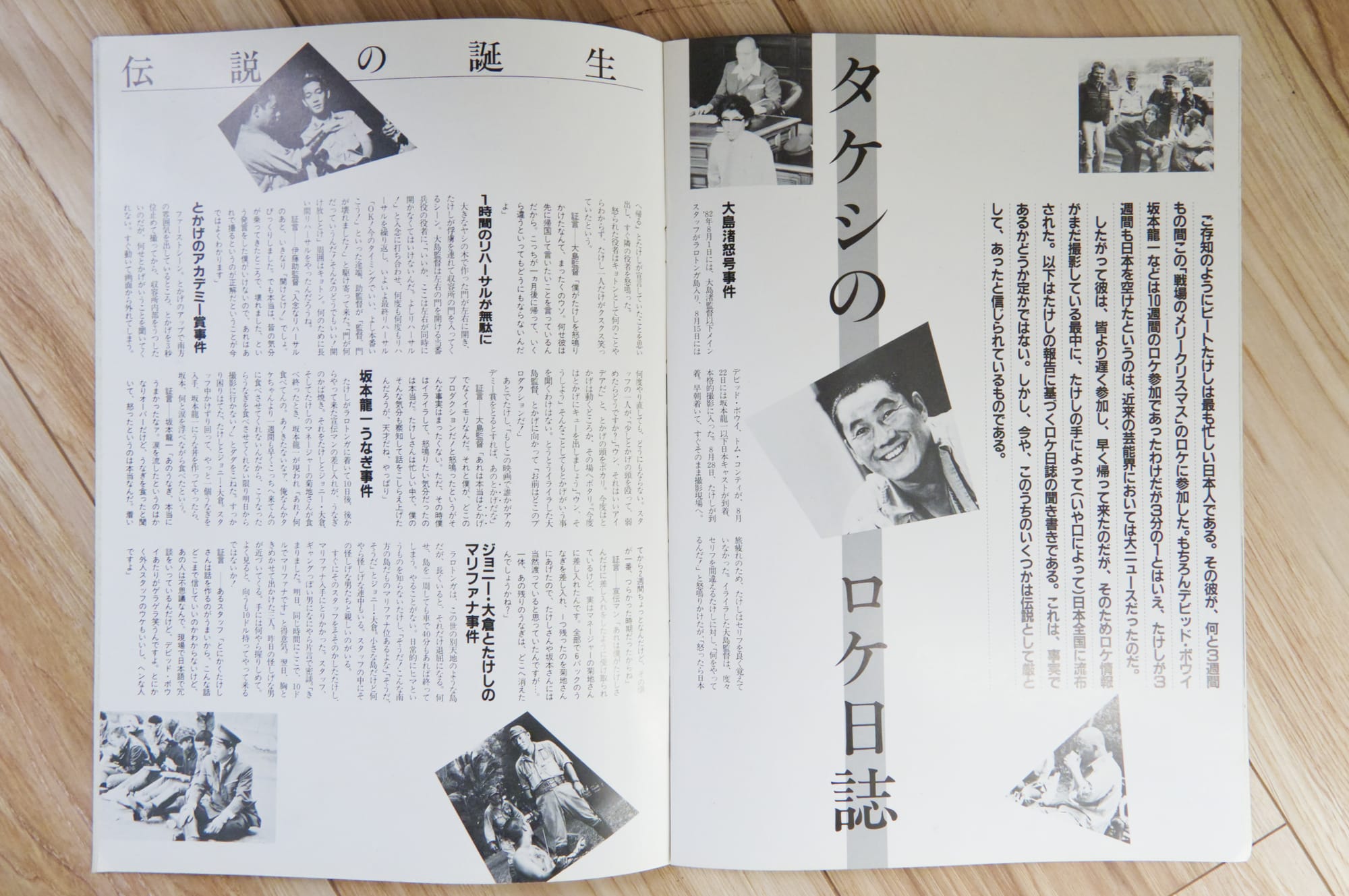

Merry Christmas Mr Lawrence was an ambitious project upon its original 1985 release: a cross-cultural project uniting David Bowie with Nagisa Oshima on a film about a US prisoner in a Japanese internment camp, with music and a prominent acting role from Ryuichi Sakamoto as well as one of the first ‘serious’ acting roles in an incredible performance from Takeshi Kitano. A groundbreaking film such as this is accompanied by a pamphlet that seeks to bring insight into the joys and challenges of bringing such a film to life.

With such a prominent role for Kitano in a departure from his career work to this point, it’s marked by an in-depth diary that ‘may or may not be true’ from his three weeks on set. Shots of the film are juxtaposed with analytical essays on the themes of the film by Ryuichi Sakamoto, and a rather touching on-set crew photo that ensures no person is left behind.

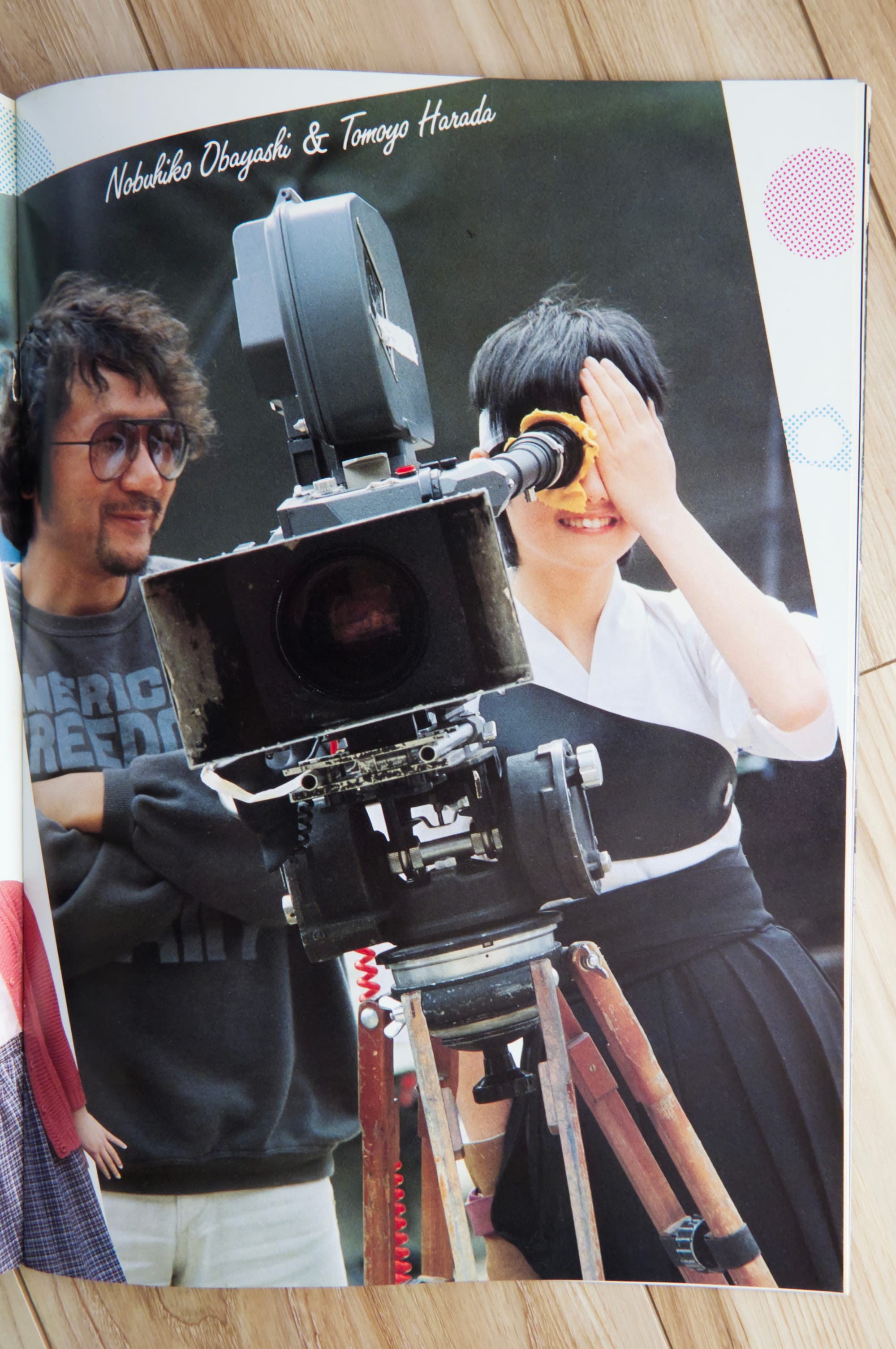

On the other hand they are time capsules. While such a trend endures today, one major factor in mainstream Japanese cinema in the 1980s would be to place popular musicians and talents from other industries in leading roles as star vehicles to attract audiences. Amongst House director Nobuhiko Obayashi’s eclectic 1980s filmography is an adaptation of The Girl Who Leapt Through Time starring idol Tomoyo Harada, and the pamphlet acts as a testament to her stardom.

While more standard in its inclusion of a story summary and plentiful stills from the film primarily promoting the idol herself (including a double-spread poster and a press conference report for an upcoming musical unrelated to the film she would star in), behind the scenes shots of Harada and Obayashi including a letter from the former to the latter and production notes make it a charming compliment nonetheless.

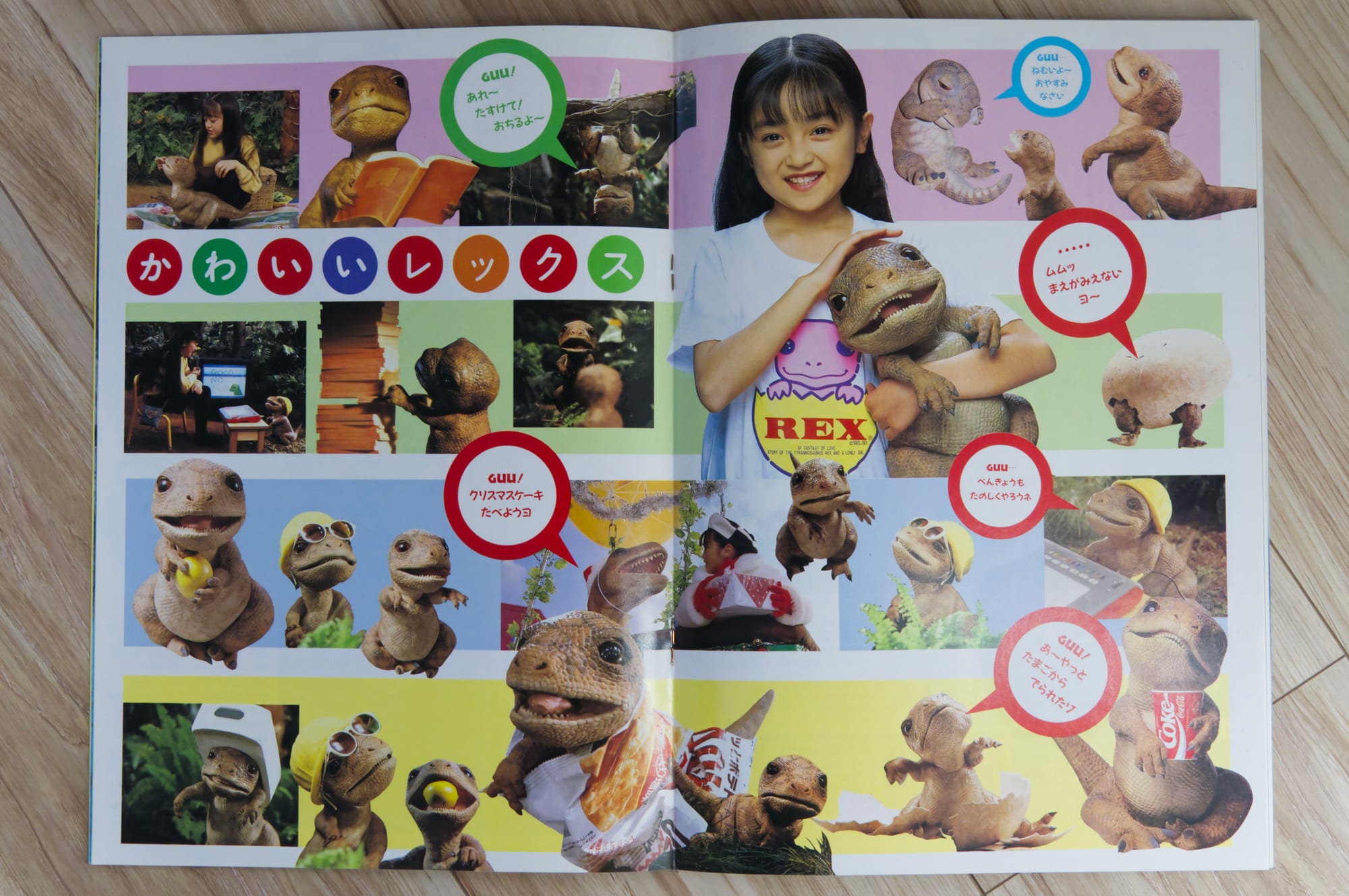

On the other hand, movies notable beyond their on-screen escapades provide a glimpse at would could have been. Rex was a 1993 summer blockbuster directed by Haruki Kadokawa, son of its founder and then-president of the company. The pamphlet shows a plethora of advertising collaborations for the adorable dinosaur and potential future mascot character including with Coca-Cola, behind-the-scenes on making the surprisingly-nimble animatronic, and more. While the film was overall a success, what’s missing is how the film was pulled from theaters 6 weeks after its opening following Kadokawa’s arrest on drug smuggling charges, killing the future this mascot may have had as seen in this book.

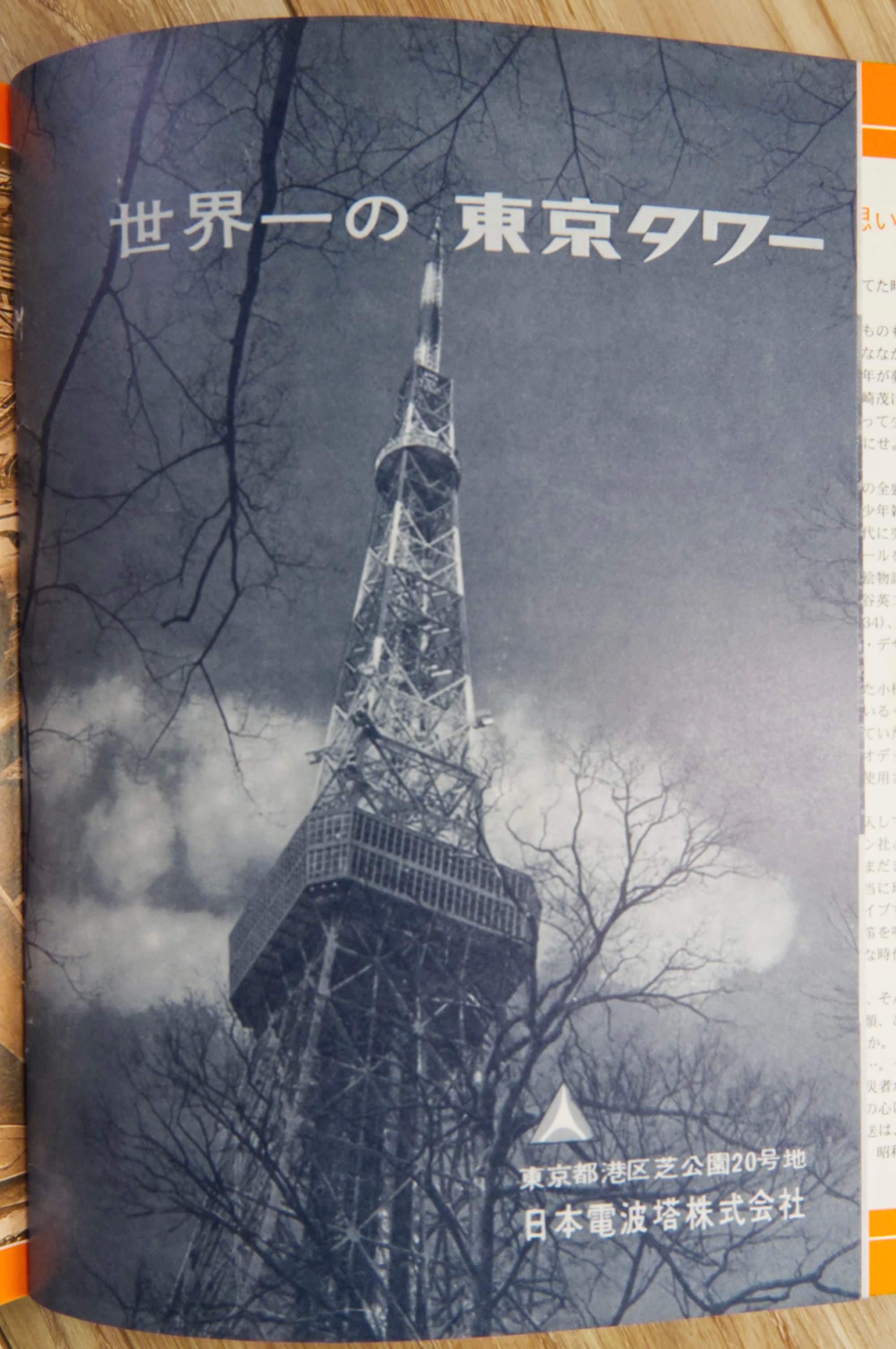

Each pamphlet marks a moment in history, while championing the potential of the medium and what it means to tell stories. Before directing Godzilla Minus One, Takashi Yamazaki achieved box office success and awards acclaim with his CG-heavy historical drama Always Sunset on Third Street. As the first film follows Japanese reconstruction in the early 1960s during the construction of Tokyo Tower this film not only includes detailed production logs on how they created the sprawling shots of historical Tokyo using miniatures and CG, it includes a replica of the pamphlet for Tokyo Tower distributed at the time.

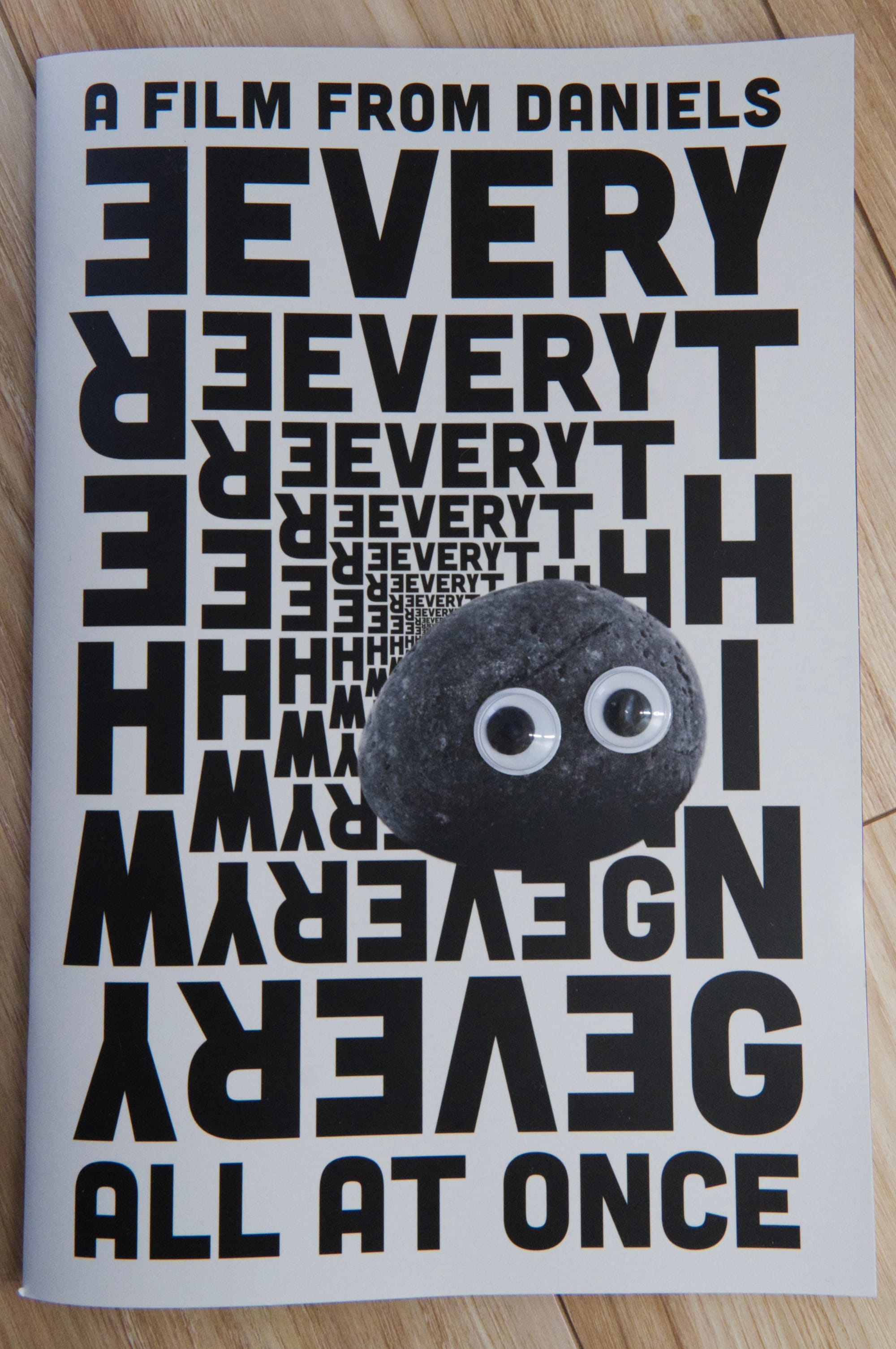

All these examples celebrate the film the exist to commemorate. Could I discuss how the Oscar-winning US film Everything Everywhere All At Once uses its pamphlet to recreate the film’s reality-hopping chaos and heart, with googly eyes for the rock on the cover and a fold-out of the donut with shots of Michelle Yeoh jumping through realities hidden underneath? How Baby Assassins: Nice Days and all films in the series include a drama CD that deepens the relationships of its characters? The script included in the pamphlet for Route 29 director Yusuke Morii’s debut film Amiko? How for indie films like i ai these can serve as creative outlets for small-time filmmakers just as much as the films themselves, with space for analysis of themes and stories of the challenges of filmmaking?

Perhaps the motion comics of Cutie Honey, the concept art of Spider-Man: Across the Spiderverse, the interview and breakdown of historical locations in Totto-chan: The Little Girl By the Window?

Movie pamphlets have a 100-year history rooted in the theater and traditions of early Japanese cinema as a mixed-media theatrical medium in itself, but today they exist as a powerful reminder of the humanity behind creating art, as well as a peek behind the curtains at filmmaking. At the minimum, they’re a reminder a film existed, and the hours that went into bringing it to life.

There’s nothing like it anywhere else, but that’s what makes the movies special.