At times it’s hard to know who Broken Rage was made for. At others you’re laughing hard enough to put your hand over your mouth at risk of making too much noise. It’s just about weird enough that it works.

First premiering last year at Venice International Film Festival before its somewhat-muted release on Amazon Prime, veteran Takeshi Kitano is trying to cram a lot into a condensed and low-budget 62-minute affair. The film is split neatly in two as it at first follows Takeshi in the role of Mouse, a ruthless assassin who is caught and interrogated by police before being offered freedom in exchange for infiltrating a drug ring. Then, the story flips on its head, replaying the story as a parody of itself that goes far enough into the absurd you’ll be wondering which half of the story is the gag by the time the credits roll.

In one moment it’ll show a tense interrogation and hit all the notes of Takeshi’s violent yakuza-addled films to the point of feeling like marks on a checklist, and in another you have the film fading to black and screening online comments from fans simultaneously mad at the blatant filler and applauding it as ‘very Takeshi’. It’s a good two-word review for the entire film, really, in all its seriousness and silliness.

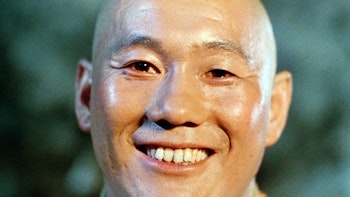

This is a person who started his career in comedy and becoming ubiquitous on Japanese TV before making the then-surprising move of starring in a serious drama alongside David Bowie with Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence. It was a show stopping performance that took his signature deadpan humor and turned it into a complex and layered performance as one of the officials in a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp. It was similarly surprising that he would go on to direct his own films, especially non-comedy films that centered hyper-violence and the yakuza coupled with more emotional drama. Then he not only released numerous acclaimed films, he became just the third Japanese director to win a Golden Lion with Hana-bi.

‘Very Takeshi’, in this case, is to exist as a contradiction. This is a comedian whose gift comes in weaponizing his unique presence and skills to get under the skin of someone for the aims of making someone laugh, cry or flinch in fear. Who is the real Takeshi? A talent, someone whose presence can make you flinch and shift emotions in an instant even if it can be hard to put the reason for that into words.

Contradiction is what makes Broken Rage work, just about. For all that it’s not impossible for a single man to exist in all these fields and succeed, what makes Takeshi unique is that his comedy and emotional range as an actor only succeed because, even if this is the first time you’ve met the man, you instinctively know who Takeshi is from a glance. He is someone embodying all these ideas at once. Of course he can write and direct and star as the same character where at one moment he’s murdering a guy in cold blood and the next he’s wearing a crude paper cut-out mouse nose and pretending to squeak.

If anything, Broken Rage feels like a film that’s very reflective of these unique traits and attempts to coalesce them into a single message (while striking a pointed target at a film industry intent on squeezing creative juice out of art in favor of the voices of the mob). It’s trying to bring the host of Takeshi’s Castle and the psychopathic teacher of Battle Royale into a single scene. Naturally, with such diverse extremes, it doesn’t always work out.

The first half of the film, the crime thriller played straight, is surprisingly plain and often boring, if frustratingly necessary. Viewed as a reflection on Takeshi combined with the condensed 30 minute runtime of the first play for this story, it makes sense that this feels more like a tribute act to better films he has produced over his career. The film hits all the tropes of the genre with laser precision, and nothing surprises or thrills you as you simply wait for it all to be over knowing exactly what will happen. There’s a cafe where Takeshi the hitman gets his jobs, gets caught, infiltrates, helps the police.

It’s almost too simple, but it makes it easy to follow.

As we enter the film’s own parody (the spin-off, as a mid-card for the film clarifies), the formulaic mundanity of what we saw so far to this point is used to its advantage by flipping events on their head. As we go to enter the same cafe, Takeshi is pushed aside by a crowd of women gossiping loudly as they work out where to go next. The chair falls apart as he sits on it and collapses to the floor, he fumbles the gun. It’s very physical, very Japanese slapstick and manzai comedy ripped from the sketch shows and comedy acts he performed at the start of his career, something that will either leave you on the floor with laughter or incredulity with little room between.

Comedians Takeshi is friends with will pop up for a single joke and disappear entirely without context. It’s stupid, but to such a degree that it works. Interrupting a confrontation with a drug dealer for an extended game of musical chairs or pretending the movie is over because a car driving two miles per hour hits a static car is so silly it flips back to being hilarious, never mind the costumes and absurdist, dry nature of other jokes that may only click with you if you’re a fan of Japanese comedy, but somehow work in spite of it all.

Underneath it all is a veiled dig at a film industry that has minimized the value of the auteur and creative vision in the modern era, countered by creating a film that unmistakably could only come from the mind of Takeshi himself. It celebrates the need to challenge cinematic convention in order to say something worthwhile. By the end of the comedy, you may even wonder if the self-serious opening half, so strictly convening to genre ideals with what almost feels like a tongue in its cheek, was the true parody.

I couldn’t help casting my mind to the director’s most recent film, Kubi, while watching this. It’s a film that weaponizes the conventions of the jidaigeki samurai film and flips them into a critique against the glorification of a warrior class whose glory-filled image manufactured in Meiji-era Japan obscures an immaturity and power-hungry insecurity that the samurai at their heart embodied more faithfully. It’s an image that, alongside the latent homosexual relations that many engaged in for reasons borne from both romance and control, don’t look as cool on a big screen, yet must be challenged if you wish to say anything that doesn’t simply play to the status quo.

Broken Rage is a film that follows in that legacy and seeks to compress the impossible career of a singular man while making a point that his success only came from circumstances an industry wants to hide, played with such absurdity that you’re left no choice but to think about it on this deeper level. It’s a smart kind of stupidity. One that doesn’t always work, but it will make you laugh. It’s very Takeshi.