Ryoko Ikeda’s Rose of Versailles was a risky proposition when it first published in the pages of Shojo magazine Margaret in 1972. Compared to the slice-of-life stories filling much of the magazine, a feminist view into the French Revolution recalling real events through the eyes of an imagined female general in the Royal Guard that reflects Japan’s own political unrest was far from standard. Yet its striking art and complex politics allowed it resonate with a generation of young girls, influence the genre for decades to come, with a story that continues to be constantly reinterpreted through TV anime, musicals by the Takarazuka Revue and beyond in areas like Korea, and even a French movie.

This power for reinvention is the key factor in the story’s continued longevity in pop culture, and for letting this story be told in new mediums and in new styles. The musicals of Korea and Japan are different, as are the other adaptations, both for better and for worse. But we already have an anime, one generally considered to be one of the best shoujo adaptations to grace the medium and a series that has stood the test of time by painstakingly adapting the complete story to a visual medium. How can a modern movie attempt to achieve in just 110 minutes what the 1979 anime achieved in almost 10x that time?

It doesn’t, nor does it attempt to. This is its own take on the classic, with interesting results that (mostly) work.

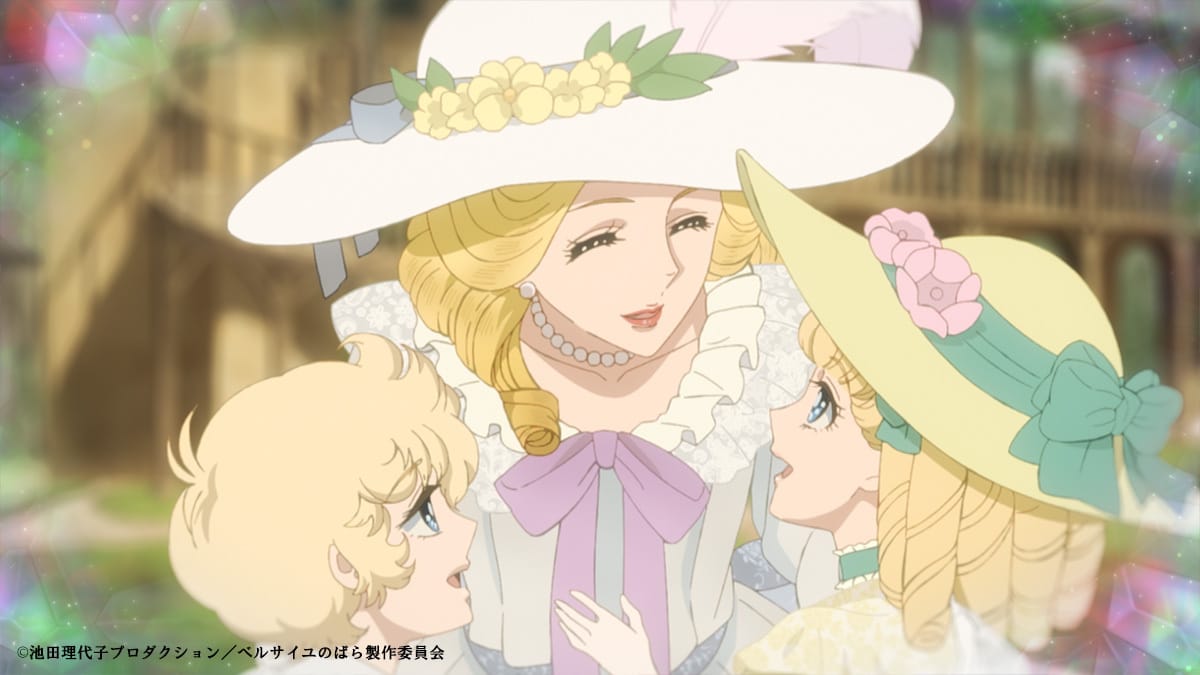

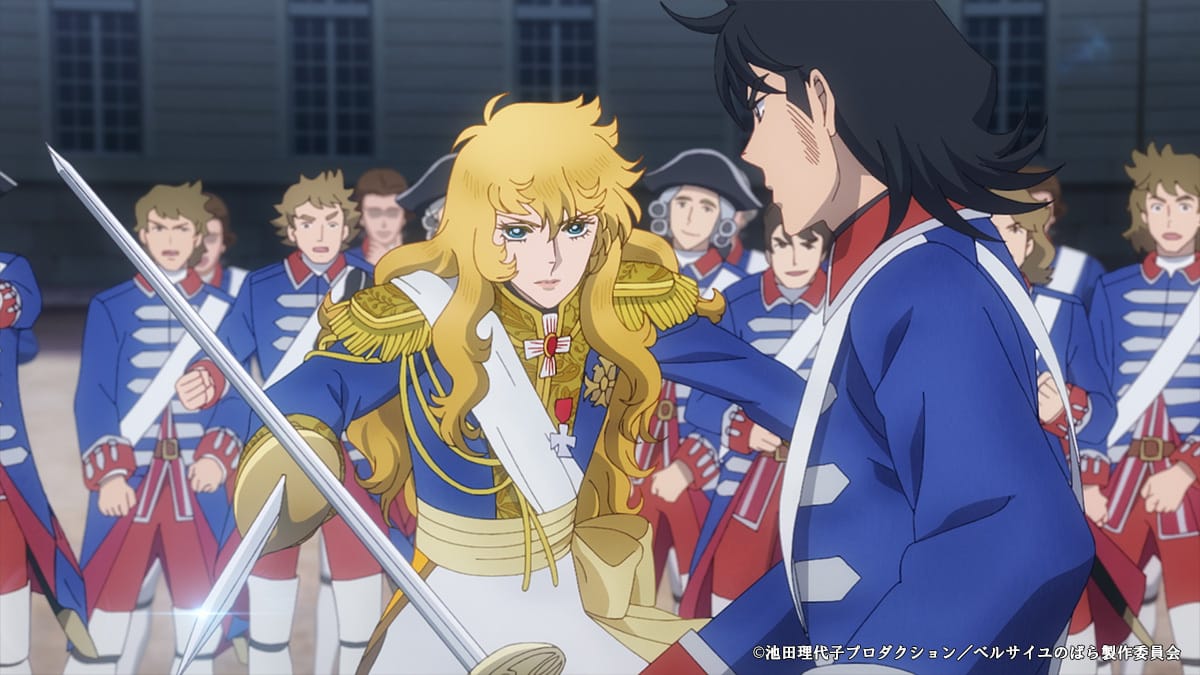

The events of Rose of Versailles begin a few years before the Revolution that would engulf Paris and bring an end to the monarchy that ruled the country. Explained in the opening narration, Marie Antoinette is an Austrian princess sent to France to marry Louis Auguste, the soon-to-be ruler of France. The hope is that the marriage of the 14-year-old to the slightly bumbling future king could strengthen both nations and bring them into cooperation with one another. The move at such a young age has left her feeling isolated as ruler without feelings for her now-husband. Protecting her is the fictional Oscar Francois de Jarjayes, raised not as a daughter but as a future commander and general of the Royal Guard.

When Marie arrives in France it is her role to protect the future queen, a task that years of training bring a responsibility and pride to the similarly-innocent Oscar. But as Marie gets more isolated and frivolous in order to block out the feelings of loneliness that accompany her life in the castle little consideration is made for the people suffering outside the palace walls. But as Oscar begins to learn the truth she sympathizes with the revolutionary sects growing increasingly influential within the local population, making her doubt her loyalties.

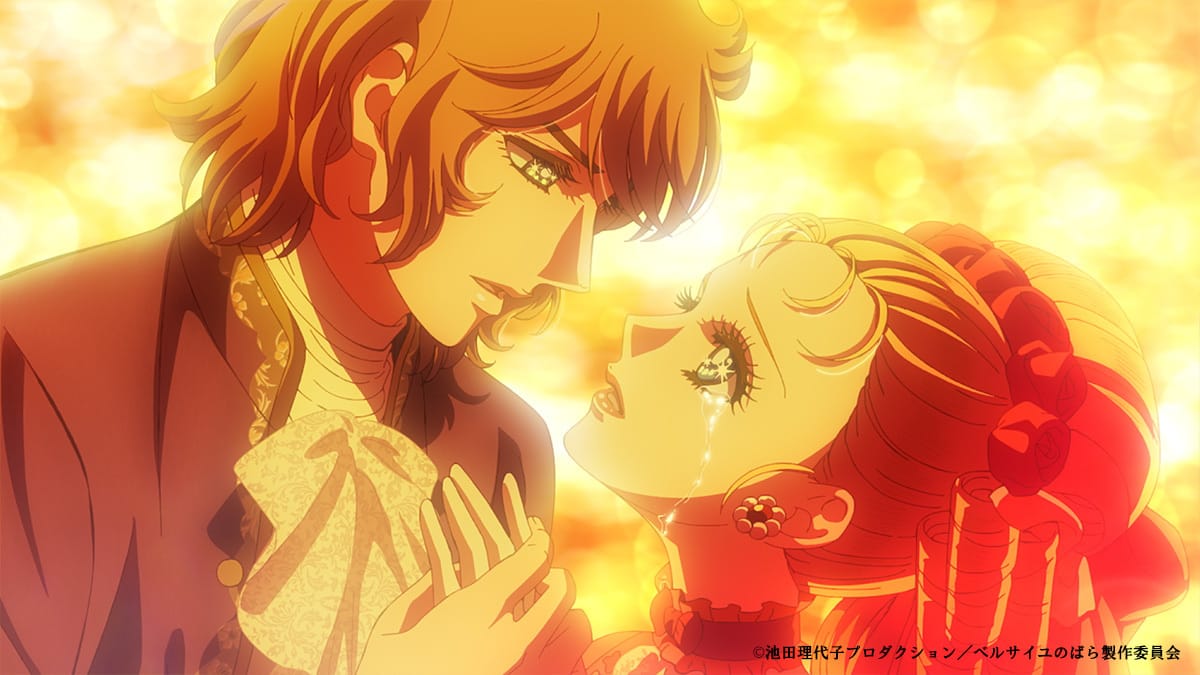

There are two aspects of this seminal shojo story that have helped it continue to resonate in the years that followed. On one, this is a radically-political story, reflective of its author as it eloquently introduced the French Revolution to contrast affairs to the state of Japan at the tail end of the student protests Ryoko Ikeda had involved herself i during the 1960s prior to publication. On the other, it tells this revolutionary tale through the vessel of love, both between Marie Antoinette and the Swedish Axel von Ferzen as a spark in Antoinette’s life doomed never to be together, and Oscar with Andre, who are each childhood friends and fellow members of the guard.

These twin romances are ones that shine a light into the aspects of power and control that weigh heavy on the minds of those on all sides of the palace walls. Marie was an influential figure, no doubt, but still lacked the power of a king and often found herself left alone far away from influence to power, leading her to romance and frivolous spending to cope. Oscar’s love prioritizes a world beyond wealth into one that reflects a populace’s ability and desire to shape their own destiny. They’re twin foils to one story.

Whether in the manga or any adaptation that follows, emotions and romance are the window into the changing world it portrays. Only by understanding this love, and particularly its intensity, can you understand the anger of the people and ignorance of power.

With this understanding, the decision to use music as montage to explore large swathes of the story in mere minutes while drilling into the emotional core of these characters is what allows Rose of Versailles to thrive in spite of its shortened runtime. Early in the film, Marie Antoinette seeks to find new excitement beyond the walls and sneaks out to a Masquerade Ball. Entering the room is like opening the door to a mysterious new world, matched in equal verve by the chanting of the masked dancers as Marie is overwhelmed until comforted by a chance meeting that makes her heart soar with Ferzen.

It’s a meeting that confirms her lack of agency: she was given no choice but to marry Louis XVI, and no amount of respect for him will make her heart race like it did for Ferzen. Knowing it can never be, his departure only makes her more erratic, and much of her isolation is once again skillfully condensed into just a few minutes via song.

It should be noted that to call this a musical would be an incorrect characterization. Beyond two songs, including the one rallying the citizens to arms to begin the revolution, all songs are performed more like music videos. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing, as this stylistic choice allows for interesting abstractions where Oscar’s internal struggles of loyalties play out like a marionette puppet, or where Antoinette’s isolation is paired with rose-covered framed windows into her life that match the opulence she indulges within. These songs are still performed by the actors, even if their pop sound can at times feel jarring to the visuals at hand.

That said, without allowing the characters themselves to sing while grounded in 18th-century France, it robs some of these characters of their core emotional beats and creates minor disconnect. As Oscar and Andre realize their feelings, we soar through the allegory of Oscar as the Greek god Mars as seen in the manga with Andre by her side, but don’t actually witness them to express this love directly.

It’s a necessary sacrifice for time, and ensures the thematic core of the story remains even when at moments it descends into a sequence of best-of moments as opposed to a sweeping odyssey. Cuts are made, naturally, and it’s particularly baffling to see Marie Antoinette’s story cut short, but you’d nonetheless struggle to feel unmoved by events once the credits begin to roll.

Those who watch Rose of Versailles as their first introduction to Okada’s magnum opus won’t be disappointed, and its musical flairs give it a new taste even compared to other musical interpretations of the story that came before it. To tell the story unchanged would make the anime meaningless, and the changes at least show desire to create something meaningfully distinct from attempts that came before, giving the adaptation a reason to exist at all.

This film, although not to the quality of the original anime or the Takarazuka Revue musicals that boast greater runtimes used to focus further on each character's conflicting emotions in this era of radical change, will nonetheless leave you pondering the same ideas Ikeda wished to express when she first serialized the manga all those years ago. Oscar’s conflicts between her gender and role, the way she is treated and how that fuels her, the fluid sexuality of people torn in their responsibilities, the contrast of opulence and strife, are all retained and updated in a manner that brings shame to how little has changed in all these years.

What was relevant in 1789 was relevant in 1972 is relevant in 2025. Rose if Versailles is a moving reminder of this.